The Proper Improper

Naming Slang's Names

[This was created for my wander round the counter-language, The Stories of Slang (2017). As ever I have tweaked it and it runs long (nearly 5K words).]

The truth, frustrating as ever, is that the bulk of slang, maybe 75%, works on standard English. No elaborate coinages, no revolutionary ground-breaking inventions, nothing plucked all new and shiny from the air. Or pretty much not so. What so much of slang is about is manipulating those ready-made coinages: playing and punning, twisting and tweaking, turning inside out and round about. Dog may have 200-plus uses in slang, but in the end they all go back to those well-known three letters (and to make things worse, a check with the etymologists shows that we don’t actually know where d-o-g comes from itself. Nor c-a-t either). Slang’s vocabulary comes mainly from the exploitation and recycling of slang’s themes. Thus the multiple synonyms of so many. But it scores badly on mint-fresh creativity.

However, slang being its gloriously, shamelessly contradictory self, there are exceptions. Sometimes there is a word, though usually some kind of phrase, that comes with a built-in tale. Whether that tale is true, well, that is, as they say, another story. I sidestep popular etymology: if you still attribute fuck to royalty-sanctioned sheet-shaking, and shit to the arrangement of a trading vessel’s cargo, then so be it. Just don’t tell me that you haven’t been told. Both loud and often.

Drunk, drink and drunkards: among slang’s central pillars. The founding father, booze, albeit as bouse, turns up in the first-ever slang glossary, penned around 1535, and is still hanging in, backed around 40 compounds (booze artist, booze hound, booze gob, boozologist, boozery...).

It comes either from Dutch (buizen) or German (bausen), which meant to drink to excess. The OED’s first use is c.1300, but this may be only refer to a drinking vessel, rather than its contents (the Dutch term is also rooted in buise, a large drinking vessel). Either way, the term really came on stream co-opted by the 16th century’s criminal canting crew. But anecdotes, while doubtless plentiful, are not suggested for etymological purposes.

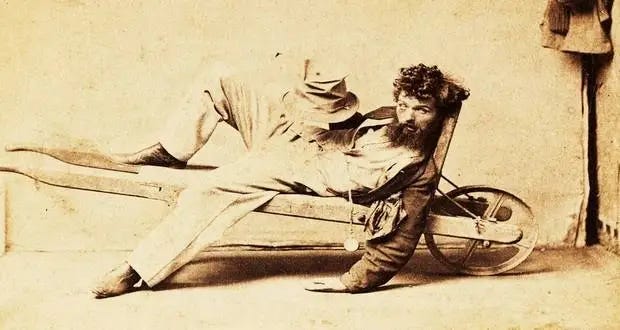

Stories do tend to accumulate round drunk, the adjective rather than the noun. Much depends on comparison, i.e. those to whom, as, bouyant yet scuttered, we pull a Daniel Boone or make indentures with our legs we seem to resemble. In many cases slang takes on the animal, bird or insect role: drunk as a bat, a boiled owl, a coon (though this may be a racial slur), a cootie, a dog, a fish, a fly, a fowl, a hog, sow, swine or pig, a jaybird, a monkey, a mouse or rat, a skunk in a trunk or a tick. Whether any of these are exceptional tipplers in nature is unlikely. No matter: slang has little time for detail. As for the humans, it’s a matter of stereotyping: contenders include a bastard, a beggar, a besom (an old woman rather than a broom), a bowdow (possibly a misconstruction of Bordeaux and thus a nod to its vintners), a brewer’s fart, a cook, an emperor, a fiddler, a Gosport fiddler or indeed a fiddler’s bitch, as forty, as a little red wagon or a wheelbarrow, a log, a loon, a lord, a peep, a Perraner, a piper, a poet, a rolling fart, a sailor, a tapster (the nearest we come to publican), or a top. Gosport was a great naval port, we can assume Jack enjoyed both drink and a merry tune. Perraner takes us around the coast to Cornwall, where St Piran was the patron of local tin miners.1 March 5th became his ‘day’ and celebrants memorialized him faithfully.

If few of these offers a story then others do. Let us start with Davy’s or David’s sow. According to the Lexicon Balatronicum, a slang dictionary of 1811, it was like this:

One David Lloyd, a Welchman, who kept an alehouse at Hereford, had a living sow with six legs, which was greatly resorted to by the curious; he had also a wife much addicted to drunkenness, for which he used sometimes to give her due correction. One day David’s wife having taken a cup too much, and being fearful of the consequences, turned out the sow, and lay down to sleep herself sober in the stye. A company coming in to see the sow, David ushered them into the stye, exclaiming, there is a sow for you! did any of you ever see such another? all the while supposing the sow had really been there; to which some of the company, seeing the state the woman was in, replied, it was the drunkenest sow they had ever beheld; whence the woman was ever after called David’s sow.

From misogyny, one slang staple, we turn to another, racism. In this case the exemplary lushington is one Cooter, also known as Cootie Brown. There are two versions. In the first we find Cooter living on the line that, in the US Civil War, divided North and South. This apparently made him eligible for the draft whichever side’s recruiting sergeant came calling. Cooter’s solution: to get drunk and stay drunk, thus rendering himself militarily useless for the duration. And so he did, with his story living on long after him. If that seems barely feasible, how about this? Cooter Brown was mixed race; half Cherokee, half African American. He was also all misanthropist, wholly drunk, and he too, though living far from the border in a shack in Lousiana, was unfortunate enough to encounter the Civil War. Given the situation he carefully dressed as a Cherokee and was as such considered a free man. Yankees and Johnny-Rebs both came to call, invariably found him drunk and shared his bottles. Cooter survived the war but not long after his shack caught fire and burned to the ground. There was no sign of its owners’ remains. Popular wisdom had it that so sodden with alcohol was the old man that he had simply evaporated in the flames. Drunk as cooter brown remains his memorial.2

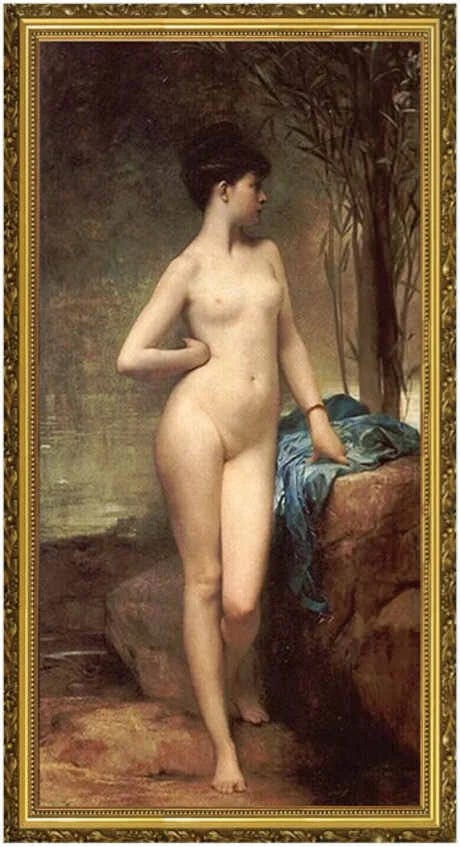

Then we have Chloe. Why Chloe? In truth, who knows. But again, there are theories. Given the phrase turns up in Australia, it may well be a back-handed reference to a notorious painting, Chloé (painted in 1875) which, having been rejected in 1883 by the Melbourne National Gallery – not only naked, she was also French and actually named Marie – had been bought by the city’s well-known Young and Jackson Hotel, where it became a point of attraction for many visitors, especially soldiers on R and R. However, back in 1789, in a poem ‘The Bunter’s3 Christening’, we meet a variety of low-lifes: ‘muzzy Tom,’ ‘sneaking Snip, the boozer,’ ‘blear-ey’d Ciss’... and ‘dust-cart Chloe’. An excellent thrash ensues to wet the baby’s head and the poem ends thus:

For supper, Joey stood,

To treat these curious cronies;

A bullock’s melt, hog’s maw

Sheep’s heads, and stale polonies:

And then they swill’d gin-hot,

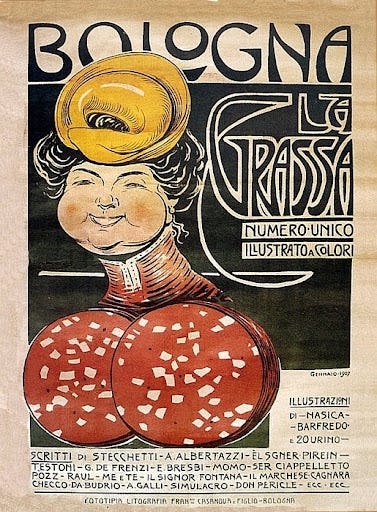

Until blind drunk as Chloe.

Which gives us our final comparison: drunk as a polony. The simple interpretation of polony, as consumed by Chloe and pals, is a Bologna sausage. Such a sausage, like a drunk, cannot stand upright and polony, to underline the image, can also mean a fool. Thus the link. However there is an alternative. French slang once gave soul comme un Polonnais, drunk as a Pole, a comparison that supposedly mocked the Polish-French Maréchal de Saxe, a great tippler.

Let us stay in Australia. And indeed at the bar. If that great but generally unloved tradition the ‘six o’clock swill’ (the pubs shut at that time, you had to drink hard and fast for the brief period that followed five o’clock knocking-off time at work) is long gone, another, the shout, remains in place. Like the UK’s round, the shout means you buy drinks for your mates, and on occasion the entire bar. But the shout is perhaps even more ritualistic. It’s not just matter of missing one’s round, but down in Godzone, nature abhors the solitary boozer. He even has a name: a Jimmy Woodser (and very occasionally Jack Smithers), applied both to the drinker and the miserable, lonely glass he’s gazing into. It is not a much-loved state. As a newspaper versifier put it in 1916:

When I ’as a ‘Jimmy Woodser’ on my own,

’Twas like someone shook the meat an’ left the bone,

The bloomin’ flavour’s left the beer,

An’ there isn’t ’arf the cheer.

It’s like torking to yerself upon the ’phone

As ever, there are rival etymologies. One ties him to an eponymous and ‘solitary Briton’ (yes, the whingeing pom, as ever), no friend of shouting, whose egregious lack of sociability was the subject of the poem ‘Jimmy Wood,’ by B.H.T. Boake, published in The Bulletin on 7 May 1892. It wasn’t that he disliked drink: ‘His “put away” for liquid was abnormal’ (his tipple being ‘unsweetened gin, most moderately watered’) but ‘he viewed this “shouting” mania with disgust, / As being generosity perverted’ and ‘vowed a vow to put all “shouting” down’. There are 14 quadruplets, we can’t have them all, but the bottom line was that Jimmy drank himself to death. The shout, however, remained undaunted.

So that’s 1892. The problem is that in 1926 a correspondent of the Brisbane Courier, offered his own take. From 1860. According to his story, around that date two rival publicans, John Ward and James Woods, had hotels [i.e. pubs] on the opposite corners of York and Market streets in Sydney. ‘Mr. Woods, in the course of business, refused to serve the female section of his customers, as by their habits they were giving his “house” a bad name, and they perforce transferred their libations to the opposition; hence the term “Johnny Warders”. Mr. Woods, having got rid of the women, had then for his customers the aforesaid barrowmen, gardeners, and casual hands and shoppers from the markets, and as the majority of these individuals, not being overburdened with wealth, usually drank by themselves, the term applied to them, and subsequently, even to the present day, given to ‘lone drinkers,’ was ‘Jimmy Woodsers.’ “ Perhaps, but Johnny Warder, at least as recorded, means not ‘woman’ but ‘drunken layabout’ (indeed its first recorded use features a female complainant, loathe to join such figures) and it was those who made their way to John Ward’s boozorium.

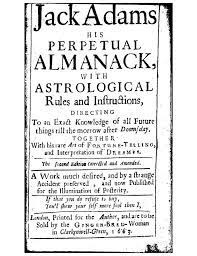

Enough Australia, at least for now. Clerkenwell lies just north-east of the City of London. The area, just beyond the city walls, was the first suburb, and with its errant population, focussed on Turnmill (sometimes Turnbull) Street running alongside the Fleet River (now Farringdon Road) has been long celebrated as the home of whores and villainy (more recently of printing and watch-making and currently of start-ups and showrooms for office furniture). Shakespeare’s Falstaff mentions it, as did many contemporary playwrights and the 19th century sociologist James Greenwood, keen to set a story against the slums, used it in a novel. It gained, of course, a slang nickname: Jack Adams’ Parish and Jack Adams alone and used generically, meant a fool.

For once we have a undisputed backstory. Jack Adams was indeed a fool, a professional one, and in time reinvented himself as an astrologer and fortune-teller. Fortunes were apparently graded: the more pay the more play and a five-guinea prognostication was far more positive than a five-shilling one (logical enough given the wealth of one who could afford the former sum). He was sufficiently well-known to bestow his name on a dance: ‘Do you know Jack Adams’ Parish’, which was still popular in the 1770s. In 1663 he brought out Jack Adams his perpetual almanack with astrological rules and instructions, directing to an exact knowledge of all future things till the morrow after doomsday. Together with his rare art of fortune-telling, and interpretation of dreams ... A work much desired, and by a strange accident preserved, and now published for the illumination of posterity. Sold exclusively ‘by the Ginger-Bred-Woman in Clarkenwell-Green’ it carried the warning: ‘If you do refuse to buy / You’ll shew yourself more fool than I’

The first use of all my eye and Betty Martin emerged in 1780 (all my eye had been there since 1728). Other versions include all in my eye and Betty, all my eye and Elizabeth Martin, my eye and Peggy Martin, and oh Betty Martin, that’s my eye. For my thoughts on this immortal lady, please see here.

Buckley comes up twice in slang. There is the question Who struck Buckley? and the dismissive Australianism Buckley’s chance.

The former is defined by John Camden Hotten as ‘a common phrase used to irritate Irishmen.’ Setting aside the justification of such irritation, Hotten went on to explain it thus: ‘The story is that an Englishman having struck an Irishman named Buckley, the latter made a great outcry, and one of his friends rushed forth screaming, “Who struck Buckley?” “I did,” said the Englishman, preparing for the apparently inevitable combat. “Then,” said the ferocious Hibernian, after a careful investigation of the other’s thews and sinews, “then, sarve him right”.’ This form of equivocation seems to lie behind all Buckley-pertinent anecdotes: the violence, the sympathetic supporter, the judicious assessment of the assailant and the replacement of valour with discretion. The Spectator, in 1912, replaced the Irishman by an unfortunate junior boy at a public school and uses it to critique Parliament’s failure do offer any more than empty bombast – and certainly no gunboats – when the horrors of the Belgian treatment of their Congolese subjects was revealed. A year later one Boris Sidis, writing about ‘The Psychology of Laughter’, resurrected the centrality of Emerald Isle: in this case the sympathetic speaker was ‘a peasant, undersized but wrathful, and with his shillelagh grasped threateningly in his hand ... going about the fair asking, “Who struck Buckley?” and again, on encountering ‘a stalwart and dangerous man,’ swiftly backed down: ‘Well, afther all perhaps Buckley desarved it.’

Australian Buckley’s, often amplified as Buckley’s chance, hope or show, has elicited a wide range of theories. Of these, which (quite erroneously) include the Yindjibarndi verb bucklee, to initiate an Aborigine boy, especially by circumcision, the best hopes lie with William Buckley (1780–1856), an escaped convict (known as ‘the wild white man’) who spent 32 years living with Aborigines in South Victoria; or a pun on name of defunct firm of Buckley and Nunn (founded by Mars Buckley and Crumpton Nunn in 1851) which states that one has two chances ‘Buckley and Nunn’, i.e. none. The main problem with William was that the phrase doesn’t turn up until nearly 40 years after his death, and in any case, whatever the vagaries of his life – both before and after his return to ‘civilization’ – chance, whether bad or indeed good doesn’t seem to come into it. The journal Ozwords (produced by the Australian National Dictionary) deals with the whole topic in its October 2000 edition (available on line). Suffice it to say that their conclusion is that Buckley and Nunn, providers of the pun, are the most likely originators.

Ireland offers Johnny Wet-bread, a teasing rather than aggressive term of mockery. Johnny existed – he was a well-known Dublin beggar who, bereft of alternatives, moistened his bread in the city’s fountains. Unlike most street people he has a memorial, albeit shared. It is to be found on a plaque at the city’s Coombe Maternity Hospital on Cork Street, where his name joins those of other city characters: Stab the Basher, Damn the Weather, and Nancy Needle Balls.

The last of these has sadly not, despite the undoubted potential, entered the slang lists. As we know, slang, is too often a man-made vocabulary. However we do have the historically proven Mrs Phillips, she of Mrs Phillips’s ware, condoms. Captain Grose explains: ‘These machines were long prepared and sold by a matron of the name of Phillips, at the Green Canister, in Half-moon Street, in the Strand.4 That good lady, having acquired a fortune, retired from business, but learning that the town was not well served by her successors, she, out of a patriotic zeal for the public welfare, returned to her occupation; out of which she gave notice by divers hand-bills, in circulation in the year 1776.’ Whether – grandmother, great- aunt? – she was related to Mrs Phillips, that brothel-keeper who, in the mid-19th century, ran a house specialising in flagellation at 11 Upper Belgrave Place in Pimlico, is alas unknown.

Nor are such women who exist strictly ‘real’. Sometimes they have been appropriated by men: typically Mrs Hand and Mrs Palm (first name Patsy) both of whom are blessed with five daughters (or sometimes sisters) who represent the hand, as used for masturbation. Five-Fingered Mary is perhaps a distant cousin.

Other generic ‘women’ include a variety of Misses and Missuses. Examples include the overdressed socialite Miss Lizzie Tish, the well-built and noisy Miss Big Stockings, the unpopular Miss Fitch, who rhymes with bitch, flouncing Miss Nancy who is not in fact a girl, opulent Miss van Neck, known for a magnificent cleavage and minatory Miss Placed Confidence, a mid-19th century term for venereal disease. Mrs Evans and Mrs Fubbs are both (literal) cats, and Mrs Fubbs’ parlour, pushing the whole pussy thing that distance further, is the vagina. Mrs Jones’ counting house is a lavatory and Mrs Greenfields sleeping in the open air. One slang area where men do not trespass is, predictably, menstruation. Among its many euphemisms are the punning Aunt Flo, Auntie Jane and sanguine Aunt Rose, Grandma George and Granny Grunts, Monica; quite how Charlie and Tommy join the party is unknown, but so they do.

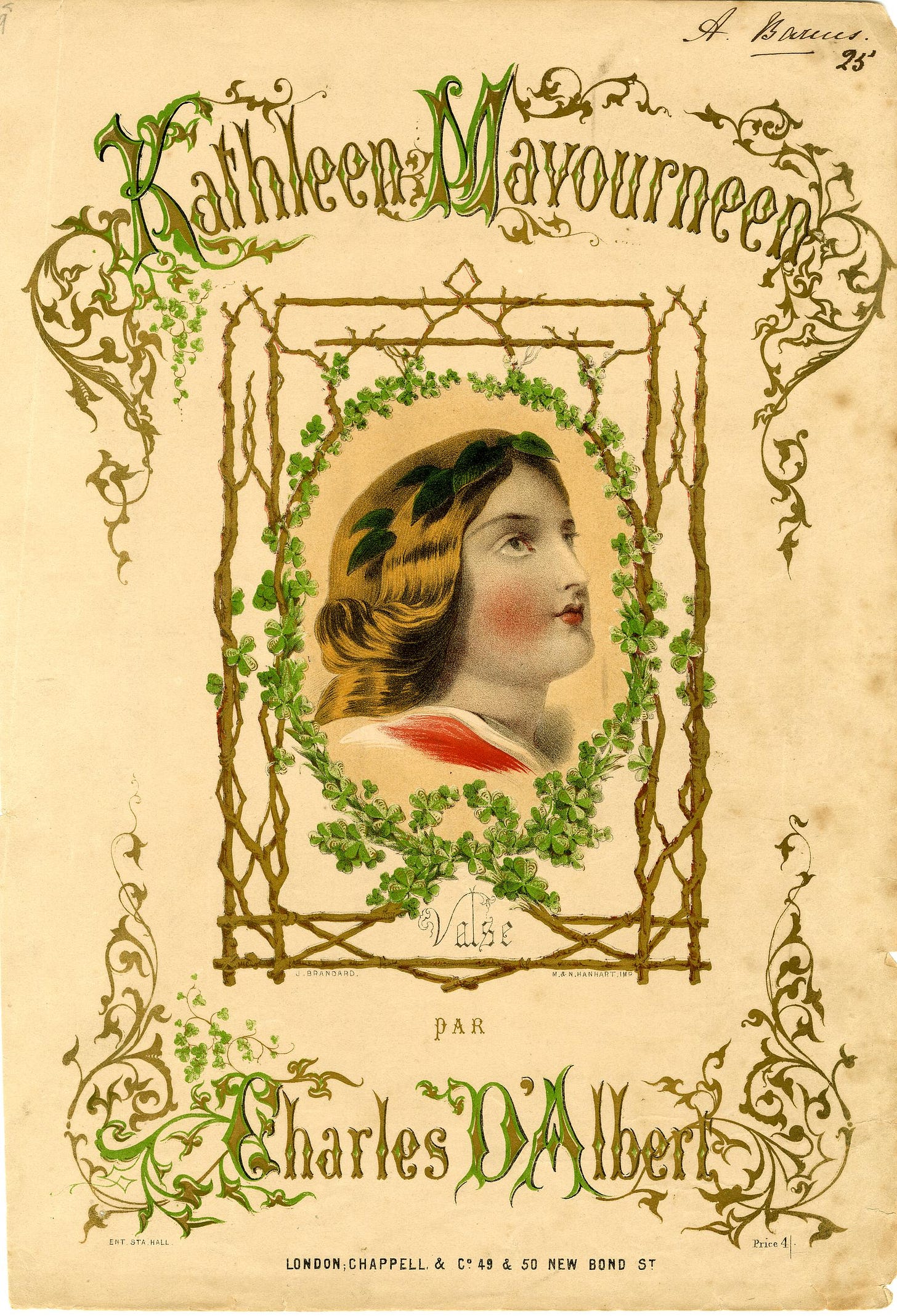

One last woman is Kathleen Mavourneen. The name, which comes from the song ‘Kathleen Mavourneen’, written in 1837 and meaning, in Gaelic ‘Kathleen my beloved,’ was initially popular in the US but its slang uses have been Australian and focus on the chorus which runs ‘It may be for years, it may be forever,’ is defined variously as an indeterminate period of time, an indeterminate prison sentence, an habitual criminal (who may be serving the former), a promise (usually in the context of a loan, which most likely will remain outstanding; businesss jargon uses the name for any defaulting debtor) and an Australian swagman’s pack (better known as a bluey) which he may carry for a lifetime. Finally there is the Kathleen Mavourneen system, Australia’s name for hire purchase

A better-known term is tell it to the Marines (the sailors won’t believe it)! which plays on the true salt’s contempt for the half-sailor/half-soldiers who once sailed alongside him, but slang has also come up with an equivalent: tell it to (or save it for, or that’ll do for) Sweeney! Both work as a dismissive exclamation of disbelief in a previous far-fetched statement. The Sweeney version seems to have emerged in the 1920s. It was likely popularised by a silent movie of that name, released in 1927 and starring funnyman Chester Conklin, but US researcher Barry Popik has it a few years earlier, first used in an advertisement for the New York Daily News, first appearing in August 1922: ‘Tell it to Sweeney! (The Stuyvesants will understand.)’ The News being a devotedly blue-collar paper, it picked Sweeney – a classic Irish name, alongside Riley, Kelsey or Kilroy, all of whom play their own slang roles – and set it against the Stuyvesants, long established among the city’s toffs. However the phrase can be pushed back a little further: to the 1910 musical The Yankee Girl, which featured the song ‘Tell it to Sweeney’. There was an even an ad, used a year earlier, which suggested to New Yorkers that ‘If you have any harness trouble tell it to SWEENEY, the leading harness maker’ but this may be coincidental. Slanged Sweeney can also mean a barber, from the fictional Sweeney Todd, the ‘demon barber’ of Fleet Street, who sold ‘golopshious’ pies made from the flesh of those he had murdered.

Further violence links to Morgan Rattler which comes from dialect and was used around 1890 to describe a hard or reckless fighter and thence a good boxer; outside pugilism it simply meant an outstanding example. But its original use came a century earlier: some form of stick with a knob of lead at one or both ends; unlike the rigid police truncheon, the stick itself was flexible, made of bamboo or metal and especially favoured as the garrotters’ weapon of choice. It could and sometimes did kill. All of which leads to its use in slang: the penis. Whether this underpinned its adoption as the name of a popular fiddle tune is unknown, but there was a song ‘Morgan Rattler’ included in Chap Book Songs around 1790 which ran: ‘At night with the girls he still is a flatterer, / They never seem coy, but tremble for joy, / When they get a taste of his Morgan Rattler.’ Terry Pratchett fans will recall the popular Discworld ditty ‘A wizard’s staff has a knob on the end.’

Animals have already cropped up as similes for drunk humans, they also boast some names on their own account. There is Mrs Astor’s pet (or plush) horse, a US term for an over-made-up or overdressed person. Mrs William Backhouse Astor Jr. (neé Caroline Schermerhorn) being the immensely rich doyenne of New York society (a.k.a. the ‘400’, that being the maximum number that could fit comfortably into her ballroom). Another horse, this time all-equine is Phar Lap, which meant ‘flash of lightning,’ and remains Australia’s most famous racehorse, since its glory days in the 1930s. In slang it means (heavy handedly) a very slow person and (gruesomely) a wild dog, with its hair burnt off, trussed up and cooked in the ashes. The phar lap gallop is (perhaps anomalously) a foxtrot.

Ireland provides a number of creatures who stand for humans who are happy to befriend whoever turns up, and will go ‘a little way with everyone’. Presumably the journey was once literal; the figurative has wholly replaced it. What we don’t know, frustratingly, is the background of any of these affectionate if less than wholly loyal creatures: Lanna or Alanna Macree’s dog, Lanty MacHale’s goat (he had a dog as well), Larry McHale’s dog, Billy Harran’s dog, Dolan’s ass, and O’Brien’s dog. All must have sprung from some local character, none bothered to explain to the wider world. Nor did Paddy Ward’s pig, a lazy person, constantly relaxing in the face of work; Goodyer’s pig, which was constantly in or causing trouble, Joe Heath’s mare, a hard worker, expanded into the phrase like Joe Heath’s mare, exerting oneself or behaving in an excited manner.

We have better luck with all on one side like Lord Thomond’s cocks, a phrase that denotes a group of people who appear to be united but are, in fact, more likely to quarrel. There was a late 18th century Lord Thomond, an Irish peer, there were a group of cocks – bred for fighting and the gambling that went with the cockpit – and there was a cock-feeder, one James O’Brien, who foolishly confined a number of his lordship’s cocks, due to fight the next day for a considerable sum, all in the same room. Stereotyped for the story as a stupid Irishman, he supposedly believed that since they were all ‘on the same side’, they would not squabble. He was wrong, and the valuable cocks destroyed each other.

Many of slang’s proper names offer no clues as to their origin, although most suggest some kind of lost anecdote. Some, e.g. Charlie Prescott (or Billy Prescot, Colonel Prescott, Jim(my) or John Prescott) for waistcoat or Dan Tucker for butter, are rhyming slang and there are dozens of similar examples which can be drawn from most of the format’s 200-year history: Harry Randle, candle, Nervo and Knox the pox, Germaine Greer or Britney Spears, beer, Posh and Becks, sex, and on it goes. But these names are mere conveniences, they rarely if ever link to their meaning, they are there for assonance not anecdote.

Finally, slang’s known unknowns, names that beg for a story. The US south-west’s Charlie Taylor, syrup or molasses into which bacon or ham fat has been poured; the mid-19th century UK’s Jerry Lynch, a poor-quality pickled pig’s head reserved for sale in slum butchers; make a Judy (Fitzsimmons) of oneself, to act the fool; Ned Stokes, the four of spades; Tom Brown, a name for cribbage and Tom Bray’s bilk, laying out the ace and deuce when playing that game; not for Joe (nor for Joseph), by no means, not on any account; Joe McGee, a stupid, unreliable person; Lady Dacre’s wine, gin, but which Lady Dacre? Mickey T, a woman who pursues powerful and/or wealthy men and spurns the rest; Johnny O’Brien, a freight train or one of its boxcars; talking to Jamie Moore, drunk and the exclamation in (or off) you go says Bob Munro. Even Roscoe or John Roscoe, so widely used for a handgun, has no known origin. There are others. Slang, frustratingly, remains careless of such tales and they may beg, but we do not receive.

I recommend this explanation: https://wunderkammertales.blogspot.com/2015/01/drunk-as-perraner.html

A cooter is a freshwater turtle, it was also the name of the Duke boys’ mechanic, ‘Crazy’ Cooter Davenport, in TV’s Dukes of Hazzard. For the latter, at least, we can assume drink was taken.

Note that Sarah Murden, writing here - https://georgianera.wordpress.com/2024/09/16/the-women-behind-18th-century-condom-making - casts the icy waters of deep research on the tale.

A great one, Jonathon, thank you!

Thank you for another great read!