[I’ve already offered some words on the ‘Vaudeville Vixen’, i.e. Eva Tanguay, a woman with a claim to have taught Mae West everything she would come to know. Here, again, taken in part from my study of women and slang Bitching (spayed1 by its publisher as Sounds & Furies (2019), I take a look at the role of (mainly) women blues singers in the magnificent proliferation of the lubricious double entendre. As usual, I have tried to fatten up the original material.

That embonpoint is very much thanks to new material sent to GDoS by regular contributor Jim Gibbons (I have mentioned him before, too): some 50-plus pages of material culled from the ‘dirty blues’ or ‘hokum’ which sparked this post. (I would stress that in no way am I a blues expert, barely a listener, and assess no more than the words it chose to use.) For instance, without his researches how else might I have found this heartfelt tribute to that oft-reviled profession, dentistry, as found in ‘Long John Blues’ and sung by Dinah Washington in 1949:

He took out his trusty drill and he told me to open wide

He said he wouldn’t hurt me but he’d fill my hole inside

Long John Long John, you’ve got that golden touch

You thrill me when you drill me and I need you very much.]

(PS The drill (as noun or verb) multitasked, also aiming for oil (vaginal fluid) and, blowing hard on his bugle, storming a lover’s trench, bayonet in hand.)

_____________________________

Slang has always found a powerful voice via popular entertainment, whether it be on stage, screen or in song lyrics. But while the ‘coster’ singers of Britain’s music halls touched on the vulgar, they still remained within ‘decent’ limits. Not so the blues singers of post-World War I America. Some of the coarsest, slangiest lines on record were sung by blues singers, many of them women, either side of 1930.

The blues, defined by the OED as ‘A melody of a mournful and haunting character, originating among the African Americans of the southern U.S.’ is first recorded as a term in 1912, in the title of W.C. Handy’s ‘Memphis Blues’. It was an extended use of the slang term blue, depressed, which had been used since the late 17th century when ‘The Wife’s Answer to the Henpeckt Cuckold’s Complaint’ of around 1688 told how: ‘He mutter’d and pouted then, the Widgeon (a fool and as such a play on gull) look’d wondrous blew.’ The OED suggests a possible link between the emotion and a physical condition whereby certain diseases render the skin colour bluish.

Initially merchandised as ‘race records’ the music was performed by and sold to the black audience. The blues offered a different take on life to the black music of the 19th century, which, in the form of spirituals, focussed on religion or its tropes. The singers, some of the best-known of whom were women, such as Ma Rainey (Gertrude Pridgett) and Bessie Smith, were talking about life in the here and now.

As its etymology indicated, that life was hard and painful, its unhappiness often engendered by failed relationships; fantasies of the hereafter with its delayed rewards, so central to African-American spirituals, did not enter the picture. As for punishments, they were already available on earth. The blues, again as opposed to spirituals, had no problem in including slang.

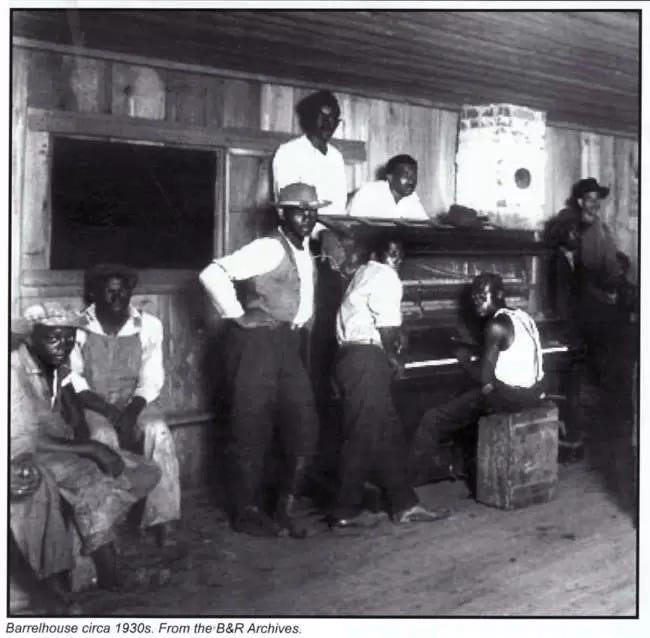

As Stephen Calt writes in his dictionary of blues language Barrelhouse Words, ‘Blues songs were not written compositions in the customary Tin Pan Alley manner, involving literary or poetic diction on at least a rudimentary level. As declaimed by the singer-guitarists and singer-pianists […] the blues lyric was a snippet of vernacular speech set to song […] Recorded blues of the period are so saturated in slang and assorted colloquialisms as to create a peculiar dialect that is only half-intelligible to present-day listeners..’[1] Blues singers used the language of the barrelhouse, the low-down nightspots where the African-American clientele could drink, gamble and hire prostitutes. The word meant the place and what one did there and it was a world that inspired W.C. Handy’s ‘Mr Crump Blues’ (1912) in which he declared that even if ‘Mister Crump won’t ’low no easy riders here. / I don’t care what he don’t ’low, / I’m going barrelhouse anyhow.’

The early blues were raw, both in emotion and vocabulary. Handy, looking to promote a wider commercialization, complained of ‘a flock of lowdown dirty blues’[2] but he was unable to stem the flow. Audiences seemed to relish the sexual references, the singers were happy to provide them. They could be unmediated, but often they resorted to double entendre. The dirty blues, as noted by Jim Gibbons, was also known as hokum. This, to me at least, is a new use of a term that the OED defines as ‘speech, action, properties, etc., on the stage, designed to make a sentimental or melodramatic appeal to an audience’ and sees as a blend of hocus-pocus, trickery and bunkum, nonsense. Quite how this links to the lyrics offered by such as Louise Bogan or Bo Carter remains debatable. Wikipedia (in an article impaired by ‘multiple issues’) suggests that while the dirty blues were ‘earnest and mature’, hokum is ‘full of sass and humor’ and has appropriated the term’s earlier use meaning coarse comedy acts as found in vaudeville. The accompanying music fits the verbal styles. Between 1928-32 ‘Tampa Red’ (Hudson Whittaker or Woodbridge on guitar) and ‘Georgia Tom’ (Thomas A. Dorsey on piano) performed as The Hokum Boys and recorded over 60 smutty songs (e.g. ‘It’s Tight Like That’, ‘Caught Us Doing It’). The genre continued into the 1950s, typically in ‘My Ding-a-Ling’, created by Dave Bartholomew in 1952 but immortalised twenty years later by Chuck Berry.

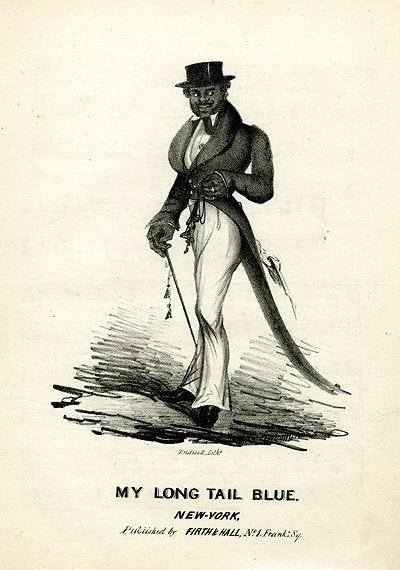

This thinly disguised smut might be discerned in 19th century minstrelsy – for instance such classic songs as ‘Long Tail Blue’ and ‘Coal Black Rose’, where Sambo alludes to being ‘’tiff as a poker’ and Rose replies’ ‘Cum in Sambo, don’t ’tand dare shakin, / De fire is a burnin, and de hoe cake a bakin’’ – but the blues singers took it to another level.2 Nor need the entendre be remotely double. Louise Bogan (born Lucille Anderson in 1897 and presumably taking the name of a well-known contemporary white poet purely by coincidence) left absolutely nothing to the imagination in ‘Shave ’Em Dry’ (1920s):

‘I got nipples on my titties, big as the end of my thumb,

I got somethin’ between my legs’ll make a dead man come,

Oh daddy, baby won’t you shave ’em dry?

while a later verse declares

‘Now your nuts hang down like a damn bell sapper,

And your dick stands up like a steeple,

Your goddam ass-hole stands open like a church door,

And the crabs walks in like people.’

In general use the song title suggests any form of aggressive, confrontational action. In terms of intercourse it has been linked to rough and peremptory sex without any preliminary foreplay by the man. To quote bluesman Big Bill Broonzy, ‘Shave 'em dry is what you call makin’ it with a woman; you ain’t doin’ nothin’, just makin' it.’ Bogan, one might suggest, assumes a good deal more female agency.

Other of her songs hymned streetwalkers – ‘Tricks [i.e. customers] Ain’t Walking No More’ – and cocaine – ‘Baking Powder Blues.’

Few singers, male or female, could follow Bogan, though ‘the master of the single entendre’ Bo Carter (Armenter ‘Bo’ Chatmon) did what he could, even if he did feel it best to mask his sexual references in somewhat obvious double entendre. His song titles included ‘Pin In Your Cushion’ (1931), ‘The Ins and Outs of my Girl’, ‘Banana in Your Fruit Basket’ (1931) and ‘Let Me Roll Your Lemon’ (1935). (‘Roll’ seems anomalous, but the lyrics make clear that ‘rolling’ is merely prefatory, perhaps a form of ‘softening up’ foreplay, to the inevitable ‘squeezing’ and the production of ‘juice’ by both parties that follows.)

In ‘Banana in Your Fruit Basket’ he sang:

Now, I got the washboard, my baby got the tub,

we gonna put 'em together, gonna rub, rub, rub

And I'm tellin' you baby, I sure ain't gonna deny,

let me put my banana in your fruit basket, then I'll be satisfied.

The ‘occupational’ lyrics of his ‘All Around Man’ could have been been taken from its forbears, with the similar sexualising of otherwise everyday jobs by eighteenth century balladeers (and collected by such as Thomas D’Urfey in his Pills to purge melancholy in 1719) home to as many species of nudge-nudgery as could be crammed in:

‘Now I ain't no butcher, no butcher's son,

I can do your cuttin' 'til the butcher man comes

'Cause I'm a all-around man, oh I'm a all-around man,

I'm a all-around man, I can do most anything that comes my hand’

Subsequent verses play on the miller (‘grindin’’), the milkman (‘pull your titties’), the plumber (‘screwin’’), the spring-man (‘bounce your springs’), and the auger man (‘blow your hole’).

Whether dirty blues or hokum, it was open to both genders. Lil Johnson brought such songs as ‘Press My Button (Ring My Bell)’ (‘Come on baby, let’s have some fun / Just put your hot dog in my bun’), ‘You’ll Never Miss Your Jelly Until Your Jelly Roller Is Gone’ (1929: ‘If you don't like my sweet potato, what made you dig so deep? / In my potato field three, four times a week’), ‘ My Stove is in Good Condition’ (1936) ‘Meat Balls’ (1937) and ‘If It Don’t Fit (Don’t Force It) (1937: ‘Now it may stretch, it may not tear at all / But you'll never pack that big mule up in my stall’). Bessie Smith sang ‘Need a Little Sugar in My Bowl’ (1929; further requests from the song included ‘a little hot dog on my roll,’ and ‘a little steam-heat on my floor’) and Dinah Washington praised that ‘Big Long Slidin’ Thing’ (1954: the ‘slidin’ thing’ was, of course, a trombone and other instruments simply didn’t cut it: ‘He brought his amplifier / And he hitched it in my plug / He planked it, and he plunked it / But it just wasn’t good enough’). Finally Julia Lee’s repertoire included the phallic worship of ‘Gotta Gimme Whatcha Got’ (1946), ‘King Size Papa’ (1948: ‘Everything that I need he carries in his king size pack’) and ‘My Man Stands Out’ (1950: ‘Down at the beach when we walk by / The other girls give him the eye / ’cause my man stands out’).

At times Bogan may have made no compromises but she was also happy to wear the mask of double entendre. She hymned the baking powder man, a braggart who like a cake had been ‘blown up’, barbecue, the vagina, i.e. ‘hot meat’, boogie alley, another term for vagina and a couple of phrases for intercourse: grind one’s coffee and get one’s ashes hauled, where ashes was a variation on ass. She also told of the B.D. Woman, who ‘ain’t gonna need no men’, and she was the first, at least as so far recorded, to use b.d. standing for bulldyke (or bull dagger) a ‘masculine’ lesbian; her younger partner, a femme, was what Bogan called a juve, i.e. juvenile.

B.D. women, they all done learnt their plan

They can lay their jive just like a natural man

B.D. women, B.D. women, you know they sure is rough

They all drink up plenty whiskey and they sure will strut their stuff

She used clap, gonorrhoea, cock, the African-American and white Southern term for the vagina, from coquille, a cockle-shell; cold in hand, impoverished, fuck (‘So I fucked all night and all the night before, baby / And I feel just like I want to fuck some more’ [3]) and fuck it, get one’s habits on, to be intoxicated by narcotics, jump-steady, alcohol, roller, a hard worker, suck for oral sex of both varieties (‘If you suck my pussy, baby, I’ll suck your dick’ [4]), tommy, a girl (around 1790 the term had originally meant a lesbian), possibly a prostitute and trick, her client.

The blues might deal with traveling (specific towns were often named), violence, partying, work and prison (some singers included the names of real-life prison wardens and guards in their songs). But many were about sex, and specifically sexual intercourse. For the last one finds action, to jam, to ring someone’s bell, to ball the jack (which is also used to mean move fast) to grind and thus coffee grinder, a lover, to jazz, to rock (and roll), and to squeeze someone’s lemon, immortalized in Robert Johnson’s ‘Travelling Riverside Blues’ (1937). In ‘Empty Bed Blues Part 1’ (1928) Bessie Smith talked about cunnilingus: ‘He’s a deep-sea diver / with a stroke that can’t go wrong, / He can touch bottom, and his wind holds out so long.’

The penis was a biscuit, thus the female lover is a biscuit roller (sex itself was a cookie and thus ‘Papa wants a cookie right now, now, now / Papa wants a cookie, papa needs a cookie / Papa’s gonna get it somehow’), the stick of candy, the lollipop, the all-day sucker, the hambone (which doubled as a vagina) and round steak; semen is jelly, baking powder, medicine and sugar. It was also a hot dog and bread, which like dough ‘rose’ and grew bigger when placed in a hot oven or stove. All good fun unless his pencil lost its lead and her ‘handy man ain’t handy any more’. The vagina is found as the coal bin, the jelly and most popularly jelly-roll, the sweet potato and the potato field; and makes regular appearances as cock, in the Southern sense. A tight one was a mouse’s ear with the pseudonymous ‘Bob Clifford’ promising in 1933, ‘Gonna take my mouse’s ear for a midnight ride (I sure am, man) / Gonna use my old straight eight ’cause it’s long and wide.’ The mainstream straight eight being an engine found in top-of-the-range automobiles. Adultery was a regular theme: the lover was a back-door or outside man (or woman) or a triflin’ man; to cheat was to dog, run around or mess around (which could also mean dance), to tip, to steamroller; an ex-lover was a used-to-be.

Sex wasn’t, however, everything, many lyrics had other subjects and offered other slang words. Examples include arnchy (i.e. ‘aren’t you…’, one who puts on airs), have a ball, boog or bring down (to annoy or depress), burner (a pistol), cop your broom (to leave), eas’man (i.e. a kept man whose life is ‘easy’) and kidman, an older woman’s younger lover, eight rock (one whose complexion is notably black), fatmouth, loco, get off or raise sand (to enjoy oneself), gimmies (a bad mood), high-stepper and high-stepping, red-hot as in ‘red-hot mama’, knock a jug (to drink), jump salty (to become aggressive), Jim (as a term of address), burn leather (to dance energetically), market (a prison), mojo, monkey man (a weak-willed man), Mose (generic for a black man), piccolo (a jukebox), play for a chump (deceive), rat (a straight-haired wig), run one’s mouth, the square (honest), strut one’s stuff, stuff (narcotics), sugar (money), Stavin Chain (a womanizer or wanderer and most likely rooted in name of the John Henry clone, and another railroad worker of legendary strength and stamina) and turn one’s damper down (to calm oneself). The phrase too bad Jim, means serious, no excuses.

[1] S. Calt Barrelhouse Words (New York 2009) p. xi, xiii

[2] q. in Calt op. cit. p. xiv

[3] ‘Shave ’Em Dry’ (1935)

If, like me, others wonder as to spay’s etymology, the OED notes that it is rooted in the Anglo-Norman espeier and the Old French espeer to cut with a sword, i.e. espee and in modern French épée, a sword.

This is a hoe, as in the agricultural implement, and not a very early use of ho, a prostitute. Popular etymology claimed that the original hoe cakes, a form of pancake and otherwise known as johnny cakes, would be baked on the flat of a hoe held over a wood fire. This has been debunked and hoe was an alternative name for a griddle: (http://www.historiclondontown.org/files/Hoe-Cake-Etymology-web.pdf)

Now I want to listen to some old blues. A favorite R&B tune of mine is "Nosey Joe" by Bull Moose Jackson, of "Big Ten Inch Record" infamy.