[Another extract from Bitching/Sounds and Furies. Women invaded the newsroom long since, but ’twas not always so. Not much over 150 years. I offered a brief rundown of the pioneers].

Journalism, hitherto a male preserve outside the predictable concerns of the ‘women’s section’ (fashion, children, all points domesticity), was invaded by the ‘stunt girl’, a young, purportedly respectable woman who thrust herself, at her editor’s behest and always undercover, into a variety of challenging environments. This was not what many felt should happen. It was the late 19th century and Victorian mores still ruled, albeit in theory. In the first place much of the work went on late at night, in the second, the ‘girl reporter’ might have to venture into unsuitable places, finally, working with men meant that she had to act like a man: journalism was ‘not an occupation which tends to the development of feminine graces.’[1] It all read clearly even if stunt never appeared in America’s short-lived lists of rhyming slang.

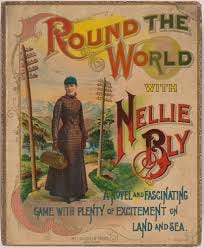

None of which stood in the way of the ‘stunt girls’. The exemplar was Nellie Bly. In 1887, aged 23 and despite a succession of knockbacks from male editors, Bly suggested a new feature to the man at the New York World. She would travel to Europe and come back in steerage class, i.e. surrounded by those huddled masses who, quitting their ‘old countries’ for whatever reason, were queuing to gain a foothold on the golden streets of the New World. The pitch fell foul of the predictable responses – she was too young, too inexperienced; the expenses would be too high – but the World had a counter-suggestion: why didn’t Ms Bly fake it as a loony and get herself locked up inside the notoriously wretched, filthy wards of the insane asylum on Blackwell’s Island. No tickets, no special wardrobe, even peasant rags, required. What followed was her series with its blunt title ‘Ten Days in a Madhouse’ recounting the adventures of one ‘Nellie Brown’ from committal to release.

A vast success, it spawned follow-ups such as ‘The Girls Who Make Boxes: Nellie Bly tells How It Feels to be a White Slave’ (in a non-sexual sense – the sexual trafficking sense had emerged around 1870 – though her report made it clear that managerial groping long predated #metoo), ‘Visiting the Dispensaries: Nelly [sic] Bly Narrowly Escapes Having Her Tonsils Amputated’ (and again seems to have fended off a male’s straying hands), ‘Nellie Bly in Pullman: She Visits the Homes of Poverty in the “Model Workingman’s Town”’ (‘I thought the inhabitants of the model town of Pullman hadn't a reason on earth to complain. With this belief I visited the town, intending n my articles to denounce the rioters as bloodthirsty strikers. Before I had been half a day in Pullman, I was the most bitter striker in the town.’) It also made room for Bly’s rivals: Ada Patterson ‘the Nellie Bly of the West’; ‘Annie Laurie’ (real name Winifred Black) or, ‘Nell Nelson’ (actually Nell Cusack) who had, among other topics, her own brand of ‘white slaves’: the makers of cigarettes. Unfortunately, projecting the ever-alluring image of ‘middle-class white girl in possible sexual peril amidst the ravening proles’, they eschewed the language of those they encountered. The white slaves provide no slang, nor do the inmates of the Island.

[1] q. in Victorian Periodicals Review vol. XXV (1992) p. 109/2

If we want to find slang in American journalism and with female by-lines, it is necessary to move on a decade or two. To a group of women, who with a fine sense of punning, have been named the ‘Mob Sisters’, the credit for which must go to Beth Fantaskey Kaszuba, whose PhD thesis on ‘women reporting on crime in Prohibition-era Chicago’ (2013) coined and incorporated the name.

Ms Kaszuba chose five female journalists, all working for the 1920s Chicago Tribune who were deputed to report on gangland when the ‘Roaring Twenties’ were at their height. They were, she explains:

Genevieve Forbes Herrick, whose byline was a fixture on the paper’s front page throughout the Roaring Twenties;

Maurine Watkins, who drew upon her work as a crime reporter to write the enduring social satire Chicago;

Kathleen McLaughlin, a confidante of mobsters whose crime reportage in Chicago earned her a coveted spot in The New York Times’s once exclusively male newsroom;

Leola Allard, who covered Chicago’s juvenile and domestic courts, reporting on crimes ranging from spousal abuse to kidnapping;

Maureen McKernan, whose clear-thinking, no-nonsense coverage of crime for the Tribune begins to move closer to the modern ideal of objective, factual reporting.

All, she suggests, shared the ‘three characteristics that defined the mob sister style: use of sarcastic humor; a pervasive cynicism; and the employment of popular, sometimes coarse, slang.’

This slang came naturally with the territory: reporting on Twenties gangland turned papers like the Tribune into adjuncts of the burgeoning world of pulp magazines and their women writers into prototype Hildy Johnsons (created in 1928 by Ben Hecht and Charles Brackett as a man in their movie The Front Page, but in the 1940 movie His Girl Friday a feisty hackette portrayed by Rosalind Russell [above]). The ‘girl reporters’ (to use their own possibly self-conscious coinage) interviewed the male gangsters (and their families, adding weddings and other social occasions to the usual roster of rods and gats and cold meat and stiffs) and descended enthusiastically on the imprisoned female occupants of what was termed Murderesses’ Row. All seemed to be perfectly aware of the necessary pose, and all came over as pleasingly hard-boiled.

Much of the slang came between an interview’s quote marks, but the writers employed it too. Thus in a Forbes Herrick interview of June 1926 her subject, an alleged cop-killer, explained how ‘You birds caught me napping...I didn’t mean to kill the dick but he had a gun and I had to plug him’ and a year earlier, kicking off a piece telling how Chicago’s Cardinal Mundelstein had refused to permit a burial service for gangster Spike O’Donnell, she wrote ‘He doesn’t carry a gat or pack a mean wallop with his fists but a middle aged man, alone and quietly, yesterday defied the O’Donnell Brothers, there are eight of them and they are mighty.’

As was she. A typical Forbes Herrick piece put her readers right next to the action:

‘Say, lady,’ shouted the sergeant over the wire when I finally got him, ‘you know the dame you wuz just chinnin’ with? Well, she done it.’

‘Done what?’ I queried stupidly. For the moment I had quite forgot that an ugly murder with a packet of poison had probably been ‘done.’

‘She bumped her old man off . . . She’s just confessed . . .’

Sophie’s in jail. Her trial’s coming along . . . And if there is a Polish equivalent for the phrase ‘nine o’clock lady,’ I’m sure Sophie will use it the first time she gets a chance on the witness stand.[1]

Elsewhere she threw in ‘slugs’ for bullets, ‘leggers’, ‘rats’ (traitors), and a reference to the rough area known as ‘the back of the yards’ (i.e. the holding pens of the city’s stockyards).’ Her colleague McLaughlin peppered her accounts with terms such as ‘chic young gun widow,’ ‘alky dealer,’ ‘moonshine’ and ‘moonshine joints,’ ‘booze sellers’ and ‘synthetic booze,’ ‘the bridewell,’ ‘on the spot’ and ‘taken for a ride.’

The era was especially fruitful in female killers and the ‘mob sisters’ lapped them up. Maureen Watkins covered the trial of alleged murderess and triple-divorcee Belva Gaertner. Faking it or for real, Gaertner seemed blithely unworried. She laughed as she told Watkins:

‘Gin and guns – either one is bad enough, but together they can get you in a dickens of a mess, don’t they. Now, if I hadn’t had a gun, or if Walter hadn’t had the gin — . Of course, it’s too bad for Walter’s wife, but husbands always cause women trouble... Now that coroner’s jury that held me for murder,’ she said, ‘That was bum. They were narrow minded old birds – bet they never heard a jazz band in their lives’.’ [2]

In what might be a foretaste of today’s ‘fake news’ and ‘clickbait’, Ms Kazuba notes a newspaper reader of 1925 declaring ‘O, I never read the papers for facts, just for thrills.’[3] Gaertner, like seemingly any attractive woman up before the Chi-town beaks, was acquitted (‘gallant Cook County’, teased the mob sisters, mocking the local authorities, and as they regularly pointed out, things were not quite so promising for plain girls); she died in her bed in 1965. Meanwhile Maureen Watkins had quit the Tribune and parlayed the Gaertner story and that of another murder suspect Beulah Annan (again attractive, again acquitted), into a play: Chicago. Originally and ironically titled Brave Little Woman, it opened in 1927 (Gaertner was at the first night of a solid Broadway run that lasted for 172 nights in all) and was filmed and revamped as a vastly successful 1975 musical (filmed in 2002). The Gaertner character, relatively minor, was ‘Velma’ (later ‘Velma Kelly’); Annan (notorious for watching the boyfriend she had just shot bleed out for two hours as she serenaded the cooling body with repeat plays of the foxtrot ‘Hula Lou’) was showcased as ‘Roxie Hart...the prettiest woman ever charged with murder in Chicago.’

The massed sob sisters appeared as a single character, ‘Mary Sunshine’. Make what you will of the fact the ‘she’ was revealed at the story’s end to be a man.

According to Genevieve G. McBride and Stephen R. Byers[4] if there was a real-life model for fiction’s Hildy Johnson (female version), then it was Ione Quinby. Quinby, with her trademark cloche hat invariably pulled down over her fashionably bobbed hair (she claimed it gave her confidence), plus a penchant for flapper-style short skirts, covered Chicago news for the city’s Evening Post. She did stunts: the first involved applying for psychotherapy. Turned down because she didn’t seem to have any problems, she only achieved the analysis when the male photographer the paper had sent along assured the shrink that she was indeed sufficiently off beam: there was the hat thing plus an apparent obsession with where her desk was placed in an otherwise male newsroom. (Quinby consistently refused to be relegated to any form of ‘hen coop’.) Another stunt took her to the circus where she appeared in full costume atop an elephant. But her story turned out to be not so much the ‘stunt’ but that of the women animal trainers and other circus females.

1She did her stints as a mob sister (covering mob weddings and funerals, major trials and interviewing Al Capone himself) and like her peers wrote up the 1924 trial of rich boys Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb (aged respectively 19 and 18), charged with killing fellow junior plutocrat, 14-year-old Bobby Franks. She liked a good gangland widow and wrote them up, no doubt, as they would have liked: When Mrs ‘Big Tim’ Murphy (given name Margaret, known as Flo) returned from church ‘to find her husband’s body sprawled lifeless on the floor’ (Tim having answered the door to the wrong visitor, most likely hitman Murray ‘The Camel’ Humphreys) ‘she threw herself down upon him and cried, “Oh, Tim, darling, why didn’t they take me too? But then I must live to avenge you”.’ After noting a marriage that had been ‘blissfully happy’ for 17 years, Quinby added ‘Except for the little interlude when Tim spent a year or two [for which read seven] at Fort Leavenworth, their home was a haven of peace and quiet.’ In the event Flo decided to pass on revenge; she wiped her tears and in time remarried John ‘Dingbat’ O’Berta, one of Big Tim’s pals.

When required, Quinby could play the sob sister, but the overall verdict was what she did was take risks. Equally important was her news policy: when she wrote about women, murderesses or otherwise, what qualified them as ‘stories’ was that what they did was news. They could be politicians, movie stars, business-women, visiting foreign royalty: for Quinby the angle was always that they were women.

The execution of killer Ruth Snyder pushed all her buttons. Light on slang, but unrestrained when it came to the lurid image, her piece was more mob than sob:

They had assembled to see a woman killed, and centuries of man’s chivalry to women seemed to rise up at that moment in a desperate urge to save the woman now crouched before them…[Ruth Snyder] whimpered again as she gazed straight toward them. The silence!...A crunching sound as the grim executioner rammed down a lever! A sinister, crackling whine, and a sputtering noise…Fascinated, unable to move, the twenty-four men were like creatures in some diabolical nightmare….As they watched, blue darts of electricity emerged from Ruth’s body in sinister spurts like small pale devils dancing about….Then came a weird silence that strained at their ears and bore down upon their minds as if weighted by sash weights….Seconds crawling slowly like wounded soldiers dragging themselves back to the trenches….Finally the guards reassembled about the chair, picked up Ruth’s inert body, and wheeled it out of the room.[5]

On the other hand when a teenage mother was jailed and was parted from her daughter, ‘Tootsie’, it was Quinby who semi-adopted the child, bringing her to the jail to see mom (the child thought she was in hospital and the matrons gave her milk and cookies).

[1] Forbes Herrick, “Nine O’Clock Ladies,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 1 May 1927, J4; ‘nine o’clock lady’ was a Herrick coinage referring to the good-time girls who invariably claimed to lead a blameless lifestyle, eschewing excess and getting to bed by ‘nine o’clock every night’

[2] “No Sweetheart Worth Killing – Mrs. Gaertner,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 14 March 1924, 17

[3] Genevieve Forbes Herrick, “Married Men in Demand as Stokes Jurors,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 5 Feb. 1925, 1.

[4] MacBride & Byers On the Front Page in the ‘Jazz Age’: Journalist Ione Quinby, Chicago's Ageless ‘Girl Reporter’ Jrnl. Illinois State Historical Soc. vol. 106 (Spring 2013) pp 91-128

[5] q. in MacBride & Byers op.cit.

from ‘Nellie Bly’ (1850) by Christie minstrel Stephen Foster; more recent (2012) and more germane is Ellis Paul’s ‘Nellie Bly’: ‘Nellie Bly, she was sly, she was like a private eye / She went under cover into a women's mental ward / Her pen was like a sword.’ © BMG Rights Management, ELLIS PAUL PUBLISHING