[I wrote this, or a version thereof, as part of my attempt to create a narrative thesarus of slang, Slang Down the Ages, in 1986. The aim was to look at the themes that underpin the great slang preoccupations. If my piece is long, so is the Jew-hatred that inspires it. Disdaining both triumphalism and victimization, I offer only one illustration. For those who prefer deeds to words, I offer this: https://pic.x.com/TNeHTEN5En. It is not coincidental that I have chosen this post today, when the stench of gloating, triumphalist, above all self-righteous anti-semitism reeks from social media and MSM alike. But then as one supposed human rights agency is keen to announce, ‘This didn’t start on October 7th’.]

The desire of race or faith or nation A to excoriate race or faith or nation B is hardwired within us. And if that ‘us’, whether based in geography or belief, represents those who sport the white hats, then it generates an irrepressible need to find a matching ‘them’ to model the black ones. From a lexicographer’s point of view such mutual vilifications represent a fruitful mini-lexicon all of their own. Whether the loathing is based on the concrete grounds of nationalistic geography, where ‘us’ delineates the denigrated ‘them’ as ‘alien’, or of belief, the multiplicity of mutually hostile superstitions that, gilded for mass consumption, are repackaged as ‘the great religions’, or on the grimly wide-ranging and usually spurious stereotypes that follow hard on the creation of the negative ‘other’, it all contributes to an extensive language of abuse.

This is not an equal-opportunity system. In sheer numbers, Britain’s old enemies - the Spanish, Dutch and French - still provide a large vocabulary, but such terms have long since lost their sting. Some we hate more than others and offer them up a greater proportion of the vocabulary of disdain. None surpass the Jews. From the Biblical linkage of abe to the jokey mispronunciation of zhoosh, GDoS records some 204 terms. No religous group comes near. In racial terms, only African Americans (388 terms) attract more opprobrium. It is interesting that Islam and its more radical devotees, openly determined to eradicate all who deny its precepts, barely attain double figures (23).

Read history and you will understand that the Jews of yesterday are the evil fathers of the Jews of today, who are evil offspring, infidels, distorters of [others’] words, calf-worshippers, prophet-murderers, prophecy-deniers... the scum of the human race ‘whom Allah cursed and turned into apes and pigs...’ These are the Jews, an ongoing continuum of deceit, obstinacy, licentiousness, evil, and corruption...

Abd Al-Rahman Al-Sudayyis, imam and preacher at the Al-Haraam mosque, Mecca 19 April 2002

In truth I admire such as Hamas and Hezbollah and their religious pupper-masters. I admire them for their honesty. They may have a little trouble with the ‘Zionist entity’ - what terrors the taboo word ‘Israel’ seems to conjure - but Jews as such? None of that mealy-mouthed ‘Zio’ bullshit as mouthed by their useful idiots, hidden behind adopted keffiyahs, all sanctimony and passionate intensity. For the terrorists (Hitler’s einsatzkommandos would have envied their body cameras) hoping to match deeds to words, it’s ‘Kill the Jews’. Straight, simple to the point.1

Just Jew-ish

Perhaps the simplest way to coin an insult is to do no more than deprive a noun of its article - ‘a’ or ‘the’. Somehow this linguistic foreshortening renders an otherwise respectable word vulnerable. A Jew, the Jew, both terms may well be used in some negative way, but stripping off the article and talking of Jew this, and Jew that confer an extra sneer, especially when the combination stresses some accepted stereotype: Jew banker, Jew pedlar and the like. Thus to reduce Jewish to Jew has the same unpleasant effect. As the polymathic Jonathan Miller noted, as part of 1961’s satirical revue Beyond the Fringe, ‘I’m not a Jew, just Jew-ish’, although that makes no-one immune.

While jewy is an obvious pejorative, often applied to matters of taste, and America’s 19th-century jew-bastard requires no translation, jew-boy, now an undeniable negative, was not always so. The term emerged in the late 18th century, when it meant what it said: a boy who was a Jew. The mood shifted as the 19th century passed and by the 1920s, when D.H. Lawrence proclaimed his hatred for the ‘moral Jew-boys’, there was no doubt about the negative image of the term. Another term, one of the oddest, is Jews’ letters (or Jerusalem letters) which refers to tattoos. Given the prohibition on tattooing (‘You shall not make gashes in your flesh for the dead, or incise any marks on yourselves...’ Leviticus 19:28) such a term seems utterly anomalous. Various theories have been put forward: that the symbols were Hebrew, that they were inscribed in memory of pious trips to Jerusalem, but the most likely surely draws on the use of the word jew in nautical slang, where it means a ship’s tailor (irrespective of religion). The link between tattooed sailors, their tailor and his needles cannot be too distant. A sucker for rhymes, slang gives a small subset of terms based on ‘Jew’ or ‘Yid’. They include buckle my shoe, box of glue, fifteen-two, five to two, four by two, half past two, kangaroo, pot of glue, quarter to two, Sarah Soo, four-wheel skid and front-wheel skid.

Like nigger, Jew has been adopted for a variety of terms, often dealing with natural products, flowers, minerals and the like. The practice appears most common in English-speaking countries and in Germany and a sample, far from exhaustive, is included here. English, whether American or English, has jewbush: a tropical American shrub possessing emetic qualities, Jew’s fish (the halibut, a Jewish favourite), Jews’ lime: asphalt (sometimes, deliberately elided as Jew slime) Jew’s mallow: a potherb, Jews’ myrtle: the ‘butcher’s-broom’ or common myrtle, Jews’ stone: a hard rock that is related to certain basalts and limestones and is used for road-mending, a jew: a black field beetle in Cornish dialect (it exudes a pink liquid and children, seeing this, would chant ‘Jew, Jew, spit blood’) and jewing: the wattles at the base of the beak of some pigeons (the reference is to the hooked ‘Jewish’ nose). A Jew’s thorn (or Christ’s thorn), is the Paliurus Spinacristi, from which Christ’s crown of the thorns was allegedly constructed. Among the most interesting is Jews’ tin, the tin found in old smelting houses in Devon and Cornwall, known as Jew’s houses because once, around the late 11th century, the Jews mined for tin in those counties. (The black beetle reference above presumably refers to some ancient memory of these black-garbed exotics.) Meanwhile goose means a Jew. Whether, as H.L. Mencken suggests in 1936, this is a reference to goose: a tailor’s smoothing iron and as such the basic tool of many immigrant Jews, or whether it is no more than a deliberately coarsened mispronunciation of Jews, i.e. ‘Joose’, cannot be ascertained

Given Names

Like the French, who are traditionally enjoined to add a saint’s name to those given to every child, Jewish names, or at least traditional Jewish names are a rollcall of theological figures, in this case from the Old Testament. Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Rebecca...they and others have all been used as synonyms for Jew for many years.

Abraham, to start with the first of the patriarchs, gives Abe or Abie, both of which play the predictable role, with an additional use by African Americans in which abie means a tailor (as we have seen, a regular stereotype). Less well-known these days is Abie Kabibble, a name that is based on the American Yiddish ish kabibble: who cares, don’t worry, and which in turn comes most probably from the synonymous German Yiddish nish gefidlt. Adopted as a catch-phrase by the vaudeville superstar Fanny Brice, the term was picked up by America’s ‘dean of cartoonists’ Harry Hershfield who in 1917 launched a character called Abie the Agent, based on one ‘Abie Kabibble’. [I have written of Abie here.]

After Abraham, Isaac, or Ikey . Which as well as Jew can also mean pawnbroker and as an adjective, wide-awake or smart (1900). Ikey-mo, adding Moses to Isaac, means a Jew, as well as a fence, a bookie and a monyelender. Jake, from Jacob, Isaac’s son, is a third synonym. Similar generics include Max, a common Jewish given name, Sol (from the wise King Solomon), and Sammy (from Samuel, although the Dictionary of American Slang suggests that the name comes from the acronym Sigma Alpha Mu, a Jewish college fraternity, whose members are called ‘sammys’), and the women Rachel (Jacob’s wife) and Rebecca (or the Hebrew Ryfka, Abraham’s wife).

Several other names have been used as part of the abusive lexicon. Initially neutral, descriptive terms, they work almost as euphemisms, as if the simple word ‘Jew’ is too much for fastidious speech. Royal decrees, pontificating on the status of the Jews during the Middle Ages used the Latin term Secta nefaria: the nefarious sect. Israelite, like Hebrew another word that began as a simple description, but gradually, as anti-semitism gathered strength, came to be an implicit term of criticism.

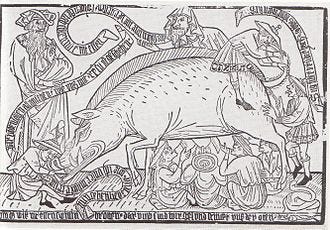

Levi refers literally to a descendant of the tribe of Levi, the third son of the patriarch Jacob; like the Cohens (occasionally used for a bookmaker), the Levites are hereditary priests, in their case responsible for such temple rituals as animal sacrifice. In the 18th century the levi was briefly a fashion accessory: a form of dress popular among women but described by Horace Walpole as ‘a man’s nightgown bound round with a belt’. Late 19th-century Britain read the Daily Levy, formally the Daily Telegraph, named for its former owner, Joseph Moses Levy while the navy’s HMS Leviathan was known by nautical wits as the Levy Nathan. Moses, another Biblical figure, has also been a source of abuse. Moses slone means Jew but in 1785 Francis Grose notes the term stand Moses, used of a man who ‘has another man’s bastard child fathered upon him, and he is obliged by the parish to maintain it’. As defined in New York police chief George Washington Matsell’s Vocabulum (1859, America’s first homegrown slang dictionary) Moses is ‘a man that fathers another man’s child for a consideration’. The phrase appeared, according to Randal Cotgrave’s Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues (1611), because traditional images of Moses show him ‘hauing [sic] on either side of the head an eminence, or luster arising somewhat in the forme of a horne’, an image reminiscent of the cuckold’s horns, and as such causing ‘a prophane Author to stile Cuckolds, Parents de Moyse’. From there Moses himself became the cuck.

Ishmael, Abraham’s son by Hagar, means literally ‘God will hear’ and has been used to mean both a Jew and an outcast, thus the celebrated first line of Melville’s Moby Dick (‘Call me Ishmael’) and Ishmael’s description in Genesis xvi. 12 as ‘one whose hand is against every man, and every man’s hand against him’. His outcast role links to another staple figure of Judaeo-Christian mythology: what France calls le juif errant and the Germans term ewiger Jude, respectively the wandering or eternal Jew. The legend of the wandering Jew, who supposedly insulted Christ as he toiled up the via Dolorosa towards Calvary and was thus condemned to wander the earth eternally, appears during the 13th century. According to Roger of Wendover’s Flores Historiarum (c.1235) an Armenian archbishop, visiting England, claimed that in 1228 he had entertained at his own table a Jew named Cartaphilus, once Pontius Pilate’s porter, who had foolishly uttered the insult, asking ‘Go faster, Jesus, why dost thou linger?’ Christ’s response, ‘I indeed am going, but thou shalt tarry till I come’, set Cartaphilus, off on his travels, never to cease until the Day of Judgement. The story took on its modern form in 1602 when a pamphlet claimed that in 1542 Paulus von Eizen, bishop of Schleswig, had met a man, this time calling himself Ahasuerus, who claimed to be the wanderer. Combining both Moses and Ahasuerus is moisher: to wander around, used in Derek Raymond’s seminal novel of upper class low-lifes, The Crust On Its Uppers (1962). The book also coined morrie, for a sharp hustler; the inference is Jewish, but those so-termed are seemingly CofE Etonians.

Another Jew, even more vilified in the Christian pantheon, is Judas Iscariot (literally ish-qriyoth: ‘man of Kerioth’), the betrayer of Christ. Judas itself means an informer, the Judas kiss is a kiss of betrayal and in prison, the Judas-hole, is a spyhole in a cell door. The Judas-colour, used of the hair or beard, is red (from the medieval belief that Judas had red hair and a red beard); Dickens’ echt-wicked Jew, Fagin, sported such a crop.

Cheats

It might be suggested that if one segregates a given individual, cuts them off from all forms of employment bar one, and ensures that the one permitted is despised by the rest of the community, then it is to add gross insult to equally gross injury to attack and pillory that individual for performing the task in question. Thus the role of the Jew: forced by Christian piety to take on the role of money-lender, he is then cursed by the pious for performing the very task with which he has been saddled.

The condemnation is international with ‘proverbs’ to match. They can be German: a real Jew never sits down to eat until he has been able to cheat, the Jews use double chalk in writing; they can be Russian: The Jew will cheat himself, when the idea strikes him, Jews do not learn cheating; they are born with it; or Polish: only the devil can cheat a Jew; or Moroccan: when a Jew smiles at a Moslem, it is a sign that he is preparing to cheat him. They can express superlatives of cunning: he can cheat a Jew, or jokily suggest the near-impossible: a Saxon [i.e. peasant] cheated a Jew, the German equivalent of a man biting a dog. They are part of the strange calculus of national abuses: One Jew is equal in cheating to two Greeks, and one Greek to two Armenians, or a Russian can be cheated only by a Gypsy, a Gypsy by a Jew, a Jew by a Greek, and a Greek by the devil (both Russian).

It is all very respectable. One need only browse the citations offered by the OED, which not until its Supplement of 1976 and subsequent Second Edition agreed to add to its entry on the noun Jew ‘As a name of opprobrium: spec. applied to a grasping or extortionate person (whether Jewish or not) who drives hard bargains’ the note ‘offensive’. To Jew: to cheat or overreach, in the way attributed to Jewish traders or usurers. Also, to drive a hard bargain...to haggle,’ and ‘to jew down, to beat down in price’ have been treated similarly: ‘These uses are now considered to be offensive.’ Nonetheless the uses are there, a positive roll-call of literary stars: Washington Irving, Henry Mayhew, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Emily Dickinson, J.M. Synge, T.S. Eliot,2 Anthony Powell (albeit in the mouth of a fictional character). If the luminaries find no problems with the concept, hallowed by centuries of Christian doctrine, why should the lumpen? And of course they do not.

In the same idiom are the nouns Jewish lightning: deliberate arson in order to gain the insurance on an otherwise unprofitable business; a Jewish waltz: the process of deal-making and haggling. The use of the bald ‘Jew’, rather than the notionally softer ‘Jewish’ merely underlines the aggression in such terms: a Jew trick: an advantage taken that is not strictly dishonest, although supposedly out of keeping with a notional business or professional code; or the verb to jew out of: to use petty, quasi-criminal means to ‘do someone out of’ something. Slang adds nearly 60 more.

Food

‘Let the goyim sink their teeth into whatever lowly creature crawls and grunts across the face of the dirty earth, we will not contaminate our humanity thus... a diet of abominable creatures well befits a breed of mankind so hopelessly shallow and empty-headed as to drink, to divorce and to fight with their fists... Thus saith the kosher laws, and whom am I to argue that they’re wrong.’ Thus also saith the fictional Alexander Portnoy (Philip Roth, Portnoy’s Complaint, 1969), and along with circumcision and a big nose, nothing defines the Jew like their abstention from pork. It has also engendered a number of put-downs. Like the ‘jokes’ that term Blacks ‘snowballs’, the charm is apparently in the opposition. The pig is the Hebrew’s enemy and pork and its other by-products Jew food, while the Jew himself is a porker, porky or pork-chopper. If we wish to describe absolute uselessness it is one of the 20 variations on ‘a pork chop at a Jewish wedding’. In the language of America’s short-order cooks, a sheeny’s funeral is roast pork and a Hebrew funeral pork chops. A bagel or bagel-bender is a Jew, as is a motza, the unleavened Passover biscuits, which can also mean money. Lox, or smoked salmon, the ‘automatic’ accompaniment to bagels (and cream cheese) gives lox jock, another synonym for Jew. Bagel has another meaning in South Africa where it denotes a spoilt, wealthy, upper-class young man; his female equivalent is a kugel, the Yiddish for cake.

Physiognomy

On a physical level, only circumcision – generally invisible – is an equally infallible guide to the semite in our midst as is the shape of their nose. Hook, hooknose, banana-nose and eagle-beak (not, of course, to be confused in any way with the proud aquilinity of the Roman nose) and schnozzole or schnozzola, best known for its application to the comedian Jimmy ‘Schnozzle’ Durante, (1893-1980), whose Italian surname, if nothing else, proves that physiognomy and ethnicity are not always so easily linked. Schnozzle comes from the Yiddish shnoitsl and, in turn, from German Schnauze, both meaning snout. The big nose imagery extends into nature, where Australia’s Jew lizard has an especially prominent snout, while in America the jewbird is a nickname for the ani, a type of cuckoo, with an arched and laterally compressed bill, and the jewcrow is the chough, another bird with a big bill. A Jew wattle is a coloured skin projection on the carrier pigeon’s bill and a Jew monkey is a type of macaque, sporting an outsize nose.

Cut-Cocks and Clip-Dicks

And then, circumcision itself. Thus, starting with the Latin curtius Judaeus: ‘the curtailed Jew’, such terms include clip(ped)-dick, snipcock (beloved of Private Eye), cut-cock and skinless. The US gay lexicon offers a Jewish compliment, a Jew’s lance, Jewish corned beef and Jewish National, which last refers to America’s Hebrew National brand of kosher salami. One who is circumcized but not Jewish is Jewish by hospitalization. A Jewish nightcap is the missing foreskin. Finally another go for Abraham: Abraham’s bosom, usually a euphemism for death, comes from Luke xvi. 22, where the phrase describes ‘the abode of the blessed dead’. Here it means the female genitals, a mysogynistic pun. Like her sisters of every origin, the Jewish woman’s images underpin the way in which stereotyping demands (and creates) extremes, even contradictory ones. She can be a wanton slut (America’s kosher cutie), from whose lascivious eyes no simple goy is safe, and almost simultaneously a frigid, sexless, castrating kvetch or ‘nag’. The popular joke defines Jewish foreplay as ‘the man pleads for sex, his partner refuses all physical contact’. And if the most alluring of all Balzac’s courtesans is the Jewish Esther (errant, beautiful, ultimately tragic daughter of the miser Gobseck), the JAP, or Jewish American Princess (all shopping, no fucking), is the fount of myriad jokes. ‘What does a JAP do with her arsehole? Send him off to work every morning’. ‘Why does the JAP like sex doggy-style? She hates to see anyone else having a good time.’

‘My Jewish Gaberdine’

Mocking the supposed Jewish propensity to pose as experts in whatever occupation they pursued, the Yiddish proverb notes that ‘When the Jew buys a gaberdine, he becomes an expert on cloth’. What is interesting is not the self-deprecation, but the term gaberdine. First encountered, in a racial context, in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice (1596), when Shylock accuses his enemies ‘You...spit upon my Jewish gaberdine’, the word seems very far from the homely gaberdine which, well known to generations of English schoolchildren, is usually called a macintosh. However the religious link is far more valid than the modern one. The term appears to come from the Old French gauvardine, galvardine or gallevardine, perhaps a derivative of Middle High German wallevart: a pilgrimage (in the same way France’s pelerin: a pilgrim, gives pelerine, a long narrow cape or tippet, usually of lace or silk, with ends coming down to a point in front). Immediate roots presumably lie in the Italian gavardina and Spanish gabardina. As used in English gaberdine has meant a form of loose smock, the garment worn traditionally by almsmen or beggars, a child’s loose frock or pinafore, a type of twill-woven cloth, usually of fine worsted, as well as the ‘Jewish’ reference. One last term, a coat-and-suiter (with its cognates suit-and-cloaker and ready-to-wear-set) refers generally to the Jews, traditionally prominent in the clothing trade. So too does ole clo (old clothes) the street cry of that other Jewish cliché, the second-hand-clothes dealer.

Health

Mockie, a slur nickname for a young Jew, may come from the proper name Moses or it may, especially in its alternative form mouchy relate to the smous or smouse, a German Jew and thus a Jewish pedlar. However a third etymology is also feasible: the Yiddish word makeh: meaning sore, pest or plague. The American term Jerusalem parrot, meaning a flea, with its implication of the ‘dirty Jew’, may well be linked to the earlier parchaty zhyd: Polish for ‘mangy Jew’. The foetor judaicus: the Jewish stench, a medico-theological term coined in the Middle Ages, could still be found in supposedly authoritative, if undisguisedly anti-semitic, tomes of the 20th century. However, as one commentator remarked, with regard to the Jews, ‘after a sprinkling of baptismal water, the Jew ceases to stink’.

One last link between Jews and illness is less unpleasant. Jewish penicillin, a joking description of chicken soup, that staple of the Jewish kitchen, and prescribed by Jewish mothers for a wide range of illnesses, really does seem to work. At least as far as colds and ‘flu are concerned. The hot soup encourages the flow of mucus through the nose, which is of proven benefit to such diseases.

‘One Who Killed Our Lord’

Of all the stereotypes the Jews qualify for two above all: the murder of the Christian messiah and an obsessive involvement in commerce and its product money. Religious prejudice underpinned anti-semitism from day one, so let us look at the first.

‘Now a Jew, in the dictionary, is “one who is descended from the ancient tribes of Judea...”, but you and I know what a Jew is: One Who Killed Our Lord [...] a lot of people say to me “Why did you kill Christ?” “I dunno, it was one of those parties, got out of hand, you know”. We killed him because he didn’t want to become a doctor, that’s why we killed him.’ Thus the Jewish-American satirist Lenny Bruce, but the black humour masks centuries of grim propaganda. As far as the Jews are concerned, the main product of nearly two millennia of Christian theology found its logical conclusion in the ovens of Auschwitz, Treblinka and the rest.

The term Christ-killer is absent from the OED, a tribute perhaps to Sir James Murray’s admirable liberalism but not to his usually all-encompassing lexicography. The term is recorded in 1830 (‘The bloody Jews, the Christ-killing rascals [...] the Christ-killers’) and is used by one of Henry Mayhew’s interviewees (‘Swindling Sal’) in his 1857 study London Labour and the London Poor, and the concept, even then, was moving towards two millennia of use. Its first dictionary citation is in Ware’s Passing English of the Victorian Era (1909). He notes that it is ‘passing away – chiefly used by old army men’ and indeed it does seem shortly after the Mayhew citation to have taken up a more prominent residence in America, its use fuelled, no doubt, by the predominantly Catholic Irish, Polish and other Central European immigrants who continued to flood the country. It lives on. One can find citations as recently as the late 1980s, and these are not historical references.

‘How odd / Of God / To choose / The Jews’: thus the clichéd jingle, but odd or not, the idea of the Jews as being chosen for a special role in the divine scheme can be found throughout the Bible. Exodus xix has God promising the Israelites a role as ‘my treasured posession among all the peoples’ and Deuteronomy x claims that ‘He chose you...from among all peoples’. If, even to believers, these are not ‘God’s words’ but a rationalization by the Jews of their apparently unique role in the world, then so be it. The image of a chosen people, a term that starts appearing in English in the mid-16th century, has persisted, as much mocked as celebrated. Another collective term is ghetto-folk, a much newer phrase, but one which stems from the placing of Jews in carefully segregated areas of towns and cities, sometimes surrounded by an actual wall. The first ghetto appeared in Venice in 1516 and its modern use, an urban area (often one of its poorest) in which a given minority group is concentrated, emerges in the late 19th-century, and was initially used to describe the East End of London - then the home of England’s Jews.

Like chosen people, the Hebrews, and thus the modern abbreviations hebe, heeb, heebie and occasionally heebess, start life in the Bible. The word began life in the Aramaic hebrai (and Hebrew hibri) which literally meant ‘one from the other side of the river’. Thus Abraham ha-hibri, in Hebrew, meaning literally ‘Abraham the passer over’ or ‘immigrant’ (to Palestine), becomes ‘Abraham the Hebrew’. The word lost its ‘h’ in Middle English, and became ebreu but regained it by the 14th century.

Other ‘Biblical’ references include America’s house-of-David boy, which refers to the second King of Israel, David, whose story is found in the book of Samuel (although in no ancient non-Biblical work whatsoever). It was King David to whom God promised that his kingdom would endure for ever and it is thus that the New Testament sees Christ as one of his lineal descendants. The ‘House of David’, nonetheless, is seen as a Jewish phenomenon, and it is that image that is mocked in the phrase.

Coined c.1820, and until World War II most common of anti-Jewish terms has been sheeny, and it remains one of the most elusive to pin down. A variety of etymologies have been proposed: the American lexicographers Wentworth and Flexner suggest, the German word shin, a petty thief, cheat or a miser. Leo Rosten, the great popularizer of Yiddish, prefers the German-Jewish pronunciation of the German schön, beautiful, fine, nice, and a word Jewish peddlers supposedly used to describe the merchandise they offered. More complex is that proposed by Nathan Süsskind in 1989. His etymology is based on the Yiddish phrase a shayner Yid: a pious (literally ‘beautiful-faced’) Jew and thus an old-fashioned and traditional Jew and one who, according to the Talmud sports the religiously proper full beard. The term was then taken up, mockingly, by assimilated German Jews who had immigrated to England, as meaning ‘an old-fashioned Jew’, i.e. in habits, clothing and religion. These ‘modern’ Jews mocked their less sophisticated successors, who followed them from Germany and clung on (at least initially) to their old-fashioned ways. The first half of the phrase, which the ‘uncultured’ Jews pronounced sheena rather than the more Germanic schön was taken up by gentile Jew-baiters to create sheeny.

A small group of religiously inclined place-names complete this section. In 1930s England the Holy Land was any predominantly Jewish neighbourhood, specifically Goldberg’s Green and Abrahampstead; the Holy of Holies was the Grand Hotel at Brighton, which around 1890 became a favourite with Jewish customers, while Brighton itself was known facetiously as Jerusalem the Golden.

Money

And finally money. The stereotype. Setting aside usury, the world of money and of commerce provides a vast arena for those who wish to typify the Jews as money-orientated. (That poor Jews are as loathed as much as are the rich is another truism).

Less popular today, but always available, America’s kike appears to spring from commercial roots. Although its etymology remains something of a mystery, and there is a reasonable case for suggesting that it comes from the Yiddish kikel: a circle, the mark used by some illiterate Jewish immigrants - rather than a cross - when signing papers at Ellis Island, New York (the immigrants’ ‘gateway to America’), others refer to the common ‘Jewish’ suffix -ki or -ski. The most likely origin may be that suggested by the etymologist Peter Tamony. He opts for the German kieken: to peep and links it to Jewish American clothes manufacturers who ‘peeped’ at smarter European fashions and produced mass-market knockoffs, popular among their poorer customers.

America also offers allrightnik, a Yiddish term that describes one who has succeeded, one who has raized himself from immigrant poverty to material success; especially used of New York Jews, it gives Allrightnik’s Row: Riverside Drive, once home to many successful Jews. Similarly Washington Heights, New York City was the Jewish Alps. The obvious etymology is all-right, as in the phrase ‘do all right for oneself,’ but in fact the term comes from the Yiddish olraytnik: an upstart, a parvenu. Such ‘new money’ does not, of course, pass unnoticed. Jewish or Yiddish Renaissance refers to any over-elaborate furniture in doubtful taste as does the upper-class English Jewy Louis, with its emphasis on fake and flashy Louis XV or XVI furniture.

But if Jews see their material success in a reasonably, albeit ironically positive light, few others share their optimism. The Afro-American term slick-’em-plenty refers to the unscrupulous trader, using his patter to gull the credulous. Late-19th-century London sneered at the Judaic superbacy: ‘a Jew in all the glory of his best clothes’ (Ware); Jews after all were more usually found in the context of rags, thus the Abraham (store) or Jew joint: the lowest level of clothes shop, usually selling second-hand goods. In law an Abraham suit is a bogus or illegitimate lawsuit, brought simply for the purpose of extortion. The Jewish or Yiddisher piano and Jewish typewriter are both a cash register or till, while the Jewish or Jew flag is a dollar bill. In US college slang a course in Jewish engineering is one in business administration and, in a similar construction, the British Army’s Jewish cavalry is the quartermaster corps, whose duties feature not gallant charges but mundane, if vital supplies. A Jew sheet is an account, often imaginary, of money lent to friends, and London’s Cockneys use as thick as two Jews on a payday as a synonym for intimacy.

Yet paradoxically, in that way that lays at the alien’s door every extreme of conduct, the Jews, with all their smartness, their money-grabbing and their avarice are simultaneously mean, cheap and impoverished. The taxation of Jews gives Jew’s eye, as in ‘worth a Jew’s eye’: something valuable or desirable. The phrase refers to the medieval practice of extorting money from the Jewish community on pain of the threatened torture of its leaders; such torture may or may not have involved blinding. Another version suggests that every organ carried a price, and that the ultimate was the eye, which would be gouged out were a wealthy Jew not to disgorge his fortune. However a further etymology, the French joaille: a jewel, cannot be discounted. In a wider sphere one finds such terms as Jewish airlines: walking on foot; Jew-bail: insufficient bail (or a promise of bail, which is not paid when the criminal absconds); Abrahams or Jewish sidewalls: white rubber sidewalls glued on blackwall tyres to make a cut-rate imitation of the real (and once fashionable) thing. Still in an automobile world, Jewish overdrive is freewheeling down hills to save petrol, while the assonant Jew Canoe refers in America to a Cadillac and in the UK to a Jaguar (commonly stigmatized as a nouveau riche, and de facto Jewish mode of transport).

‘No Christian is an Vsurer’

Writing in 1551, the scholar and politician Thomas Wilson (?1525-81), stated (in The Rule of Reason), ‘No Christian is an vsurer’. Given the expanding economy of Tudor England, his remark was hardly accurate, but as a figurative statement it served perfectly to sum up the position of the men who lend money and take interest for their pains. But if the usurer was not a Christian, then who was he? The answer, as any of Wilson’s readers would have known instinctively, was a Jew. (Even if Jews, expelled in 1290, would not return until 1656. The thought, in Jew hatred, always suffices). Based in the Latin usus: use, and thus to ‘use’ money (to make a profit), usury had always been reckoned amongst the greatest sins by Christian theologians. Its practice became grounds for excommunication and the Jews, who were in any case forbidden to involve themselves in any of the more mainstream trades, were conveniently positioned to be given this theologically burdensome but economically vital employment. If the fictional Jew has two predominant images, then while one is Charles Dickens’ Fagin, a repository of centuries of grim stereotyping (for whose creation Dickens would never really make amends), then the other is Shylock, created by Shakespeare in The Merchant of Venice.

The play premiered c.1598, yet for all the anti-semitic mythology that runs with the profession, the use of Shylock as a synonym for usurer is a mid-19th-century construct. It remains popular: Peter and Iona Opie reported in 1959, in their collection of schoolyard wit and wisdom, that among the names schoolchildren used for Jews were ‘Yid, Shylock, or Hooknose’. Meanwhile the term had crossed the Atlantic, to be used by such slang-wise writers as Damon Runyon. A shylock or shy became the accepted term for a money-lender. His ethnicity was irrelevant. The American cant term shyster, a dispreputable lawyer, may have links to shylock, but may equally well come from shicer, itself based on the German scheiss: shit. A twist on the usual meaning came in the 1920s when, with a (subconscious) nudge at the old stereotypes, America was known in Britain as Uncle Shylock (a play too on Uncle Sam) thanks to her insistance on repayment of the debts incurred by Europe during World War I.

Conclusion

My subtitle notes ‘weeper’ to ‘zio’. For the former one thinks of the long payes, sideburns, worn by the ultra-orthodox and thence the Piccadilly weeper, similar but sported by 19th century toffs. But semitic weeper is a mid-17th century one-off and probably refers to a goyish image of Jews imploring God. As for zio…but wait: we are assured by the current zealots, that they have no animus towards Jews (whatever their mentors in Hamas and environs may more honestly proclaim). Fair enough, but like so much else in their monochrome cosmography, what a lexis they reject.

I looked, for Israeli terms for Arabs, at a list of IDF slang, armies being great generators of such. I suggest this: https://sonicinbeijing.blogspot.com/2011/06/slang-army-hebrew-klalot-curses.html. One might expecta solid block of racism, but the primary role of Arabs seems to be supply root terms for many words. Such insults there are are as often aimed at Sephardi (North African) Jews, who are considered de facto stupid and vulgar.

Had one doubts about the Anglo-American poet Eliot, a devoted High Anglican, his deliberate juxtaposition of the two kinds of ‘vermin’ in Gerontion (1920) — ‘The rats are underneath the piles / The jew is underneath the lot. Money in furs’ — makes his position clear.

Great post, Jonathon. Btw, Ish Kabibble was the stage name of Merwyn Bogue (1908-1994), a Jewish American comedian and cornetist in the Kay Kyser band. https://www.eriehistory.org/blog/the-history-of-ish-kabibble

Thanks for writing. I was looking primarily at pejoratives, but I do have _rabbi_ in GDoS: https://greensdictofslang.com/entry/hpnzafi. Maybe I should have included it. My first recorded use is 1932, it may be older but searching online would be challenging.