John Phillips: a slang Don Quixote

A new hero of slang

The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha by the Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (?1547-1616) was originally published in two parts (1605, 1615) and is widely acknowledged as the first, and posibly greatest modern novel. To date there exist 29 English translations, the first by Thomas Shelton (1612) and thereafter there came a regular succession. Their reception, as such things go, was varied. Some good, some bad, some found a curate’s egg, others the golden one of goose production. One alone seems to have elicited complete agreement. The second translator after Shelton, John Phillips (nephew of John Milton and brother to the lexicographer Edward) received a resounding nul points. As decades and centuries passed there has been not a single-nay-sayer. As Samuel Putnam, whose own translation appeared in 1949, declared: Phillips’ version of the classic tale ‘cannot be called a translation.’

Phillips1 had begun his ‘literary’ career as a pro-Commonwealth pamphleteer, weighing in on behalf of his famous uncle, author of Paradise Lost and much else, in the wordy wars that accompanied the English Civil War and its aftermath. Milton was happy to acknowledge his ‘low style’.

From here his prolific output focused on the piss-take: his special targets were superstition, excessive religiosity and all forms of credulity. In 1660 he created his own satirical almanac and a ‘wizard’ to helm it: Montelion, 1660, Or, The Prophetical Almanack [...] by Montelion, Knight of the Oracle, a Well-wisher to the Mathematicks [i.e. both mathematicians and astologers] (1660). One good thing required another another, or at least a sequel and it came in 1672: Montelions Predictions, or the Hogen Mögen [i.e. both ‘great’ and ‘Dutch’] Fortuneteller.2

There was also a mock romance Don Juan Lamberto, or a comical history of late times by Montelion Knight of the Oracle (1661), which mocked the excesses - political, apocalytic - that followed Oliver Cromwell’s death.

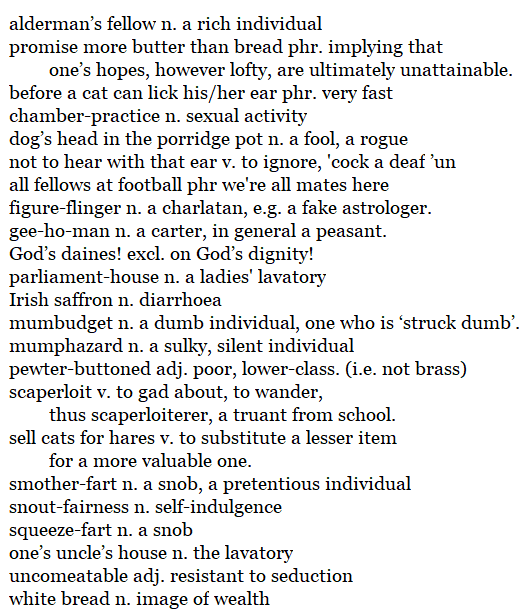

Reading through Phillips’ spurned translation, we find (and may well have missed a few, thus is reality) 43 terms that I at least have yet to list. I offer 23 examples, with definitions. What Phillips offers is, so far the sole citation. But a further pursuit, researching the researched for post- and pre-1687 examples, may change all that. Enough with those concrete but fallible ‘first use’ dates. Wait and see.

What is notable and perhaps to be expected, since 1687 is far gone even for standard English, is that most of these have slipped quietly away. If I put them in GDoS, as I shall come the next update, it is to record that once they lived, but not to suggest lexical longevity. Some lasted a while, if changed, but not many. Irish saffron (the ‘real’ version of which was an Irish export at the time), remade as Hibernian saffron, returns in Peter Motteux (another who reviled Phillips’ Quixote), in a burst of faecal synonyms as found in his Gargantua & Pantagruel (1694):

‘Do you call this what the cat left in the malt, filth, dirt, dung, dejection, faecal matter, excrement, stercoration, sir-reverence, ordure, second-hand meats, fumets, stronts, scybal, or spyrathe? ’Tis Hibernian saffron, I protest.’

Farts are smothered and squeezed, but not in nominal compounds and no snobbery or pretention is involved. The figure-flinger, the fake fortune-teller, exists, but by other names, and white bread, a survival, has been tweaked to mean establishment or conservative.

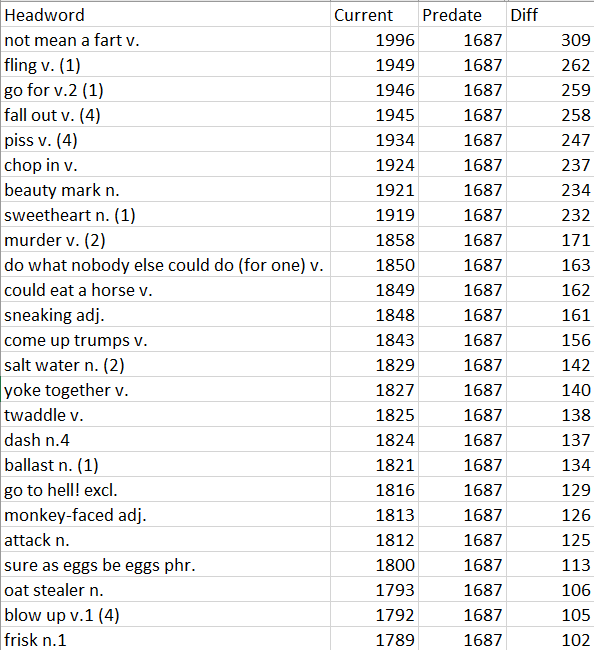

There are 61 predates, pushing known ‘first recorded uses’ backwards. I offer those 25 that exceed a century in their revision date. These are, of course, wholly temporary. Definitions, etymologies, senses and of course cited examples can be checked in GDoS.

A last thought. Phillips, writing in the late 17th century, amassed so many new terms and predates of known ones, and the text in all brings 313 citations to GDoS. This makes him, beyond the nascent ‘slang lexicography’ of purpose-researched glossaries (still primarily of cant or criminal slang), a heavy hitter. As I read on, and these major predates and as-yet unknown coinages rolled off page after page I kept asking: how did he know this stuff? where exactly did he find it all. My instant thought was The New Dictionary of the Canting Crew, by the otherwise unknown ‘B.E., Gent.’ but that appeared in 1698, 11 years later. They overlap but Phillips takes pride of place. As far as we know, there are no previous ‘dictionaries of slang’ in the 17th century; glossaries, yes, plays which showcased a small set of terms, yes, the odd criminal confession, yes…but nothing that he could pluck from the shelf as Harrison Ainsworth might do in writing Jack Shepard (1839) or similar criminal mellers. The simple possession of so wide-ranging a slang vocabulary (and the vast bulk is slang and not cant) makes him a rare figure for his era.3 Checking a selection of his terms - neither ‘new’ nor ‘predates’ - the sources are varied and inconsistent. Did he read and note all these texts? It may not have been the library, but the tavern, where he found his necessary vocabulary. This was the stuff that he found within his own head. Just as, and he was much reviled for it, he substituted British for Spanish topography, for instance in this rollcall of some of London's top sordid centres:

[H]e himself had pursu’d the same Chace of Honour in his Youth, travelling through all parts of the World in search of bold Adventures; to which purpose had left no corner unvisited of the Kings-Bench Rules, the skulking holes of Alsatia, the Academy of the Fleet, the Colledge of Newgate, the Purliews of Turn-boll, and Pickt-Hatch; the Bordello’s of St. Giles’s, Banstead-Downs, Newmarket-Heath : the Pits of Play-Houses, the Retirements of Ordinaries, the Booths of Smithfield and Sturbridge.

A paragraph wherein we find two contemporary criminal sanctuaries, two prisons, two red-light zones (near one of which - Turn-boll, or these days Turnmill St - I was was lucky enough to live), an all-purpose criminal centre, a couple of race-tracks, the front rows at the theatre and the back-rooms of eating houses, and a couple of big annual fairs.

John Phillips. A true hero of slang.

for an authoritative treatment of Phillips’ seditious and satirical career, his influences and his works, with a focus on his Don Quixote, please see Anna K. Nardo ‘John Phillips, John Milton, “Don Quixote”, and the Disenchantment of Romance’ in Mosaic 47:2 June 2104 pp 169-86.

The origin of this slang use was the Dutch Hoogmogendheiden, literally ‘High Mightinesses’, the title of the country’s ruling States-General. As a slang adjective it meant variously pretentious, strong (as in drink) and Dutch.

The exemplar, of course, is Thomas Urquhart, whose translation of Rabelais’ Gargantua & Pantagruel was published in 1653. The ‘logo-fanatic’ Sir Thomas provides me with 180 citations, 149 of which were previously unrecorded (and often coined by the autor himself).