[Herewith, part 2 of my chapter on Flappers from Sounds and Furies (2019). ]

********

Fast young ladies notwithstanding, it is hard to claim any other embryonic forms of flapperdom, a movement spearheaded by young women, almost wholly represented by their increasing numbers and which in its nascent form of girl power subordinated males to disposable, interchangeable boyfriends or fathers, their authority rendered zero, who served only as bankers. Created in Britain, remade and vastly popularized in the United States, it spread, still driven by that same highly identifiable cohort, across large sections of the world. There had been noticeable groups that were mainly composed of young people, before. The various gangs of New York City, typically the Bowery Boys, the larrikins of working-class Sydney and other Australian cities, the market-trading costermongers of London, but in every case, girls and young women were subordinate. What the American city gangs of the Fifties would term ‘debs’. Adjuncts to their boyfriends and lovers, they might ape but they did not yet initiate. Certainly not in the realm of the slang that came with such groups.

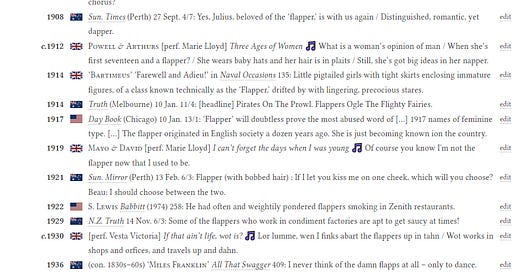

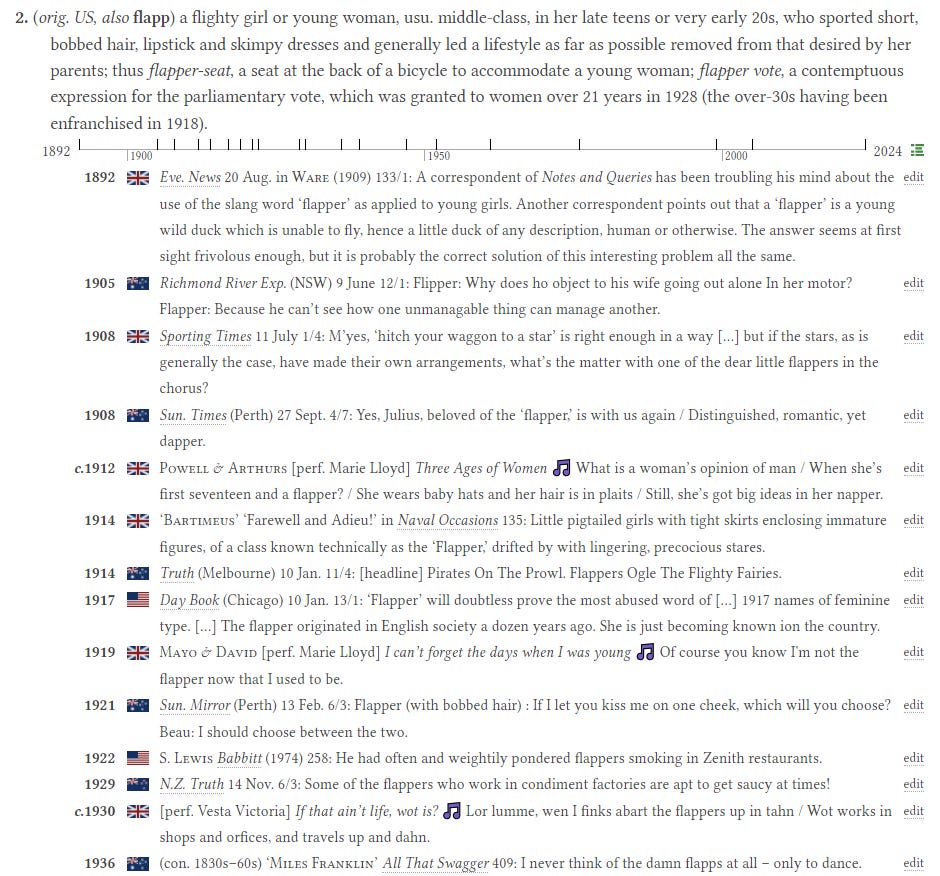

But if the physical flappers were seen as emerging almost from nowhere, or certainly in the highly publicized and increasingly stereotyped form they took in the 1920s, the word certainly has a linguistic background which one can assess. The story is, however, somewhat tangled. The prevailing belief is that flapper comes from an 18th century use of the word to mean an unfledged bird, typically a partridge or wild duck: its wings flap enthusiastically but give no traction. A secondary etymology, less common, is older still and given that the word at least emerged as slang, predictable: the 17th century dialect term flap, meaning ‘a woman or girl of light or loose character.’ As the author of a glossary of Northumberland Words put it in 1892: ‘A young giddy girl [...] or a woman who does not settle down to her domestic duties.’ Last, the Berkshire dialect vlapper, ‘applied in joke to a girl of the bread-and-butter age.’

The term was already common enough in 1892 for the London Evening News of 20 August to ponder its origins. It noted the ‘fledgling’ theory and agreed with it, and added something of its own: ‘The correspondent of Notes and Queries has been troubling his mind about the use of the slang word “flapper” as applied to young girls. Another correspondent points out that a “flapper” is a young wild duck which is unable to fly, hence a little duck of any description, human or otherwise. The answer seems at first sight frivolous enough [ed. little duck could be used of any alluring young woman], but it is probably the correct solution of this interesting problem all the same.’ That opinion stands, although the word may be underpinned by SE flap, to act in an emotional manner, supposedly typical of such young women.’ It was never noted at the time, but flapper also fitted perfectly into a long-established slang trope: the equation of women with birds. Aside from bird itself, such terms have included hen, biddy, chick, chickabiddy, quail and pheasant. None are actively abusive; all are somewhat condescending.

Thus the supposed roots. The usage is somewhat more contrary. The earliest slang use of flapper as applied to a girl is first recorded in Barrère & Leland’s slang dictionary of 1889: ‘Flippers, flappers, very young girls trained to vice, generally for the amusement of elderly men.’ A term that prefigures modern slang’s chicken.

First examples are ambiguous, and the earliest are all British: In 1909 the Tatler claimed that ‘ The first appearance of a ‘flapper’ at a ladies' golf championship was in 1895, ...in these two long-haired, long-legged colleens were the two most famous lady golfers the world has yet produced.’ Surely no naughtiness, let alone paedophilia implied there. Merely the patronising colleen for Irish women. The Sporting Times (11 July 1908), its roué’s eye always on ‘the ladies’, referred leeringly to ‘the dear little flappers in the chorus’ and in 1914 the usually squeaky-clean naval propagandist ‘Bartimeus’, in Naval Occasions, described how ‘Little pigtailed girls with tight skirts enclosing immature figures, of a class known technically as the “Flapper,” drifted by with lingering, precocious stares.’ Contemporary Australia had no underage trollops, but prior to 1920 generally used flapper in the Berkshire sense, to describe a young girl, probably a teenager, who is not yet considered old enough to be part of adult society. The image was often of a girl who had not ‘put up her hair’, and possibly still wore pigtails. Yet this too was debatable: thus the ogling men as recorded in a Queensland newspaper of August 1901, ‘Will you introduce me to those girls? That second one on the near side was simply perfection. The flapper didn’t look half so bad, either.’ ‘May I ask which of them you call the “flapper”?’ I said severely [...] ‘Why, the little one, the half-fledged youngster.’

Australia also offered a male flapper, the inference being effeminacy, rather than the flapper’s own desirable and presumably heterosexual sheik of later years. (Even if the echt-sheik, Rudolph Valentino who starred in the eponymous movie, disturbed ‘real men’ who found his perfect looks lacking macho). Sydney’s satirical Truth noted in 1913 that ‘The male flapper is very prominent in Sydney just now.’ Calling him a ‘modern marvel’ the writer was unimpressed: ‘Some folks say that the haberdasher and tailor built him, and that the barber scented and perfumed him. As for perfume, the average male flapper [...] stinks as odorous as a patchouli-bespringled dame from questionable quarters.’ His wrists go unremarked: they were presumably limp.

Quite when the meaning shifted from vice to what was seen as frivolity, however shocking and socially disruptive at the time, is hard to judge. By the late 1910s the definition, while still that of a young girl, had softened: the flapper was now a flighty, but not actively ‘immoral’ girl or young woman, usually middle-class, in her late teens or very early 20s, who sported short, bobbed hair, lipstick, skimpy dresses and stockings rolled deliberately below the knee (indicating her lack of the corset to which they would otherwise have been attached) and generally led a lifestyle as far as possible removed from that desired by her parents. The type would become associated with America, but its origins, it seems, were British and Chicago’s Day Book newspaper, perhaps confusing its definitions, confessed in January 1917 that ‘The flapper originated in English society a dozen years ago. She is just becoming known in the country.’

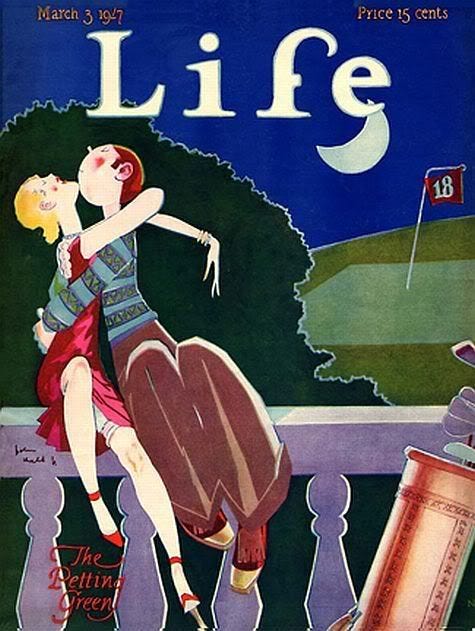

By 1922 when the flapper’s fictional antithesis, Sinclair Lewis’ mid-West bourgeois George F. Babbitt ‘weightily pondered flappers smoking in Zenith restaurants’,[1] the change was set in stone. She entered the movies, whether played by Colleen Moore or Clara Bow, the cartoonist John Held Jr. drew her for ‘slick’ magazines such as Vanity Fair [2], and her fictional embodiments were championed above all by F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose first collection of short stories in 1920 was entitled Flappers and Philosophers and whose wife Zelda was stereotyped as the style incarnate. Fitzgerald emphasized not just her independence, but also what seemed an outrageous sexuality. ‘None of the Victorian mothers,’ he put it in his best-selling novel This Side of Paradise (1920) ‘ — and most of the mothers were Victorian — had any idea how casually their daughters were accustomed to be kissed.’ Depending on one’s age, the subsequent line ‘any popular girl he met before eight he might possibly kiss before midnight’ was either appalling or aspirational. Popularized in America she re-crossed the Atlantic. P.G. Wodehouse hymned the fictional exploits of a number of her British sisters. Never one for sex, Wodehouse preferred what he termed the flappers’ espièglerie (playfulness): to steal from Richard Usborne’s Wodehouse at Work (1961), the only thing a Wodehouse girl such as Bobbie Wickham or Stiffy Byng would be doing in a Wodehouse chap’s bedroom would be making him an apple-pie bed.

She could be claimed for feminism and identified as a sub-group of another phenomenon of the post-World War I era, the ‘New Woman’, though her ambitions were less political than social. Still, earning her own money, and determining and pursuing her own desires (the more physical of which were helped by far more easily available contraception), the flapper offered at least one side of feminism. It may be hard to equate such gravity with the great army of wannabes from the sticks but she represented ‘a genuinely subversive force. Willing to run the risks of their independence as well as enjoy its pleasures, there were good reasons for them to be perceived as women of a dangerous generation.’ [3]

What she was not, however, was a modern teenager. She was sometimes of the right age, though generally a little older, she moved in a world distinct from that of conventional adults, and as we shall see, she was a great coiner of slang, but there one must halt. The word teenage can be found in 1921 (‘in one’s teens’ has been recorded in 1684), but the modern concept of the teenager as representing a segregated social group is a creation of the 1940s, if not the decade that followed; it required rock and roll for the teenager proper. The flapper cannot thus be a teenager any more than could her late 19th and early 20th century contemporaries, whether at school or college. Lists of high-school and college slang had emerged by 1910 but while a flapper naturally picked up the odd term from her college-attending boyfriends, typically those meaning drunk, she still chose her own coinages. In both cases examples of both slangs would, as youth talk does, eventually filter into each other’s world, and beyond that to the adults, but a distinct line can be seen between the nature of such lists and any representative lexis of flapper-talk.

What she was, undoubtedly, was part of what at least initially, was a closed world. It helped if you were rich, attractive and had access to the new and fashionable watering holes. A member of what the press, not to mention Evelyn Waugh in Vile Bodies, termed ‘the Bright Young People’. As such she elicited the inevitable mixture of fear and fascination, and once that had worn off and the guest list had expanded to take in the entire country, commercial exploitation. The media picked her up quickly: the coverage was almost benign. The often vituperative social critic H.L. Mencken, the scourge of so much that middle America saw as admirable, gave them a very gentle ride. Writing of the emerging style in his magazine the Smart Set in 1915, he explained:

Observe, then… this American Flapper. Her skirts have reached her very trim and pretty ankles, her hair, newly coiled upon her skull, has just exposed the ravishing whiteness of her neck. […] Youth is hers, and hope, and romance and —

Well, well, let us be exact: let us not say innocence. This Flapper […] is far, far, far from a simpleton. An ingénue to the Gaul she is actually as devoid of ingenuousness as a newspaper reporter, a bartender, or a midwife. The age she lives in is one of knowledge. She herself is educated. She is privy to dark secrets. The world bears her no aspect of mystery. She has been taught how to take care of herself. […] She is opposed to the double standard of morality and favors a law prohibiting it…

This Flapper has forgotten how to simper; she seldom blushes; it is impossible to shock her. […] She is youth, she is hope, she is romance — she is wisdom!

These were early days: her skirts had some way to rise, and bobbed hair would leave no need for coils, but Mencken’s positive take was not that different to The Flapper’s description of the type. Not everyone agreed. In 1920 the London Times, debating what would come to be known, dismissively as ‘the flapper vote’, i.e. allowing the vote to women under 30, railed against the ‘frivolous, scantily-clad, jazzing flapper […] to whom a dance, a new hat or a man with a car is of more importance than the fate of nations’. As Judith Mackrell notes [4] ‘newspapers […] bristled with warnings of the destabilizing effect these flappers might have on the country, as an unprecedented generation of unmarried and independent women appeared to be hell-bent on having their own way.’ That, given the near two million imbalance between the decimated male survivors of the War and their female compatriots meant that such women were labeled as ‘surplus’ in the tabloid press, did not allay any fears. On the other hand, even if sidestepped by the moralists, all these women were good for business, be it providing them with fashion or entertainment.

In 1922, back in America, when the world had reached what modernity might label ‘peak flapper’, the Los Angeles Times chose to quote the machine politico and ex-masseur ‘Bath-house John Coughlin,’ better known as a Chicago alderman of more than usual corruption than a reliable social commentator. ‘A flapper is a youthful female, beauteous externally, blasé internally, superficially intelligent, imitative to a high degree. Her natural habitat is the ballroom, the boulevard and the fast motor car. She browses about the trough of learning, picking as her tidbits smart phrases which she glibly repeats without sensing their meanings. She comes from all walks of life and has for her main requirement nerve, a face and figure, either actually beautiful or susceptible to artistic effort.’ The attack on flapper superficiality was no doubt meant to sting, but perhaps the old ward heeler recognized some of his own. His remarks as to her enjoyment of ‘smart phrases’ and her coming ‘from all walks of life’, were actually right on the ball.

Some critics might have been expected to know better. On the other hand, perhaps not. Mae West, who was hardly over the hill herself, indeed in the midst of penning some of the Jazz Age’s most sexually controversial plays, turned out in this interview of 1929 not to be a fan. But then again, her style, if not the moment of her celebrity, was based thirty years in the past.

‘The wicked women of old days were more fascinating because there was real get-up and glamour to her. Nowadays the flappers take the edge off it for everyone else. Even if flappers aren’t “mean” they look it. They don’t conceal a thing, either of their feelings or otherwise....Nowadays the girls all look alike – same build, slim and sexy, short skirts, same kind of stockings, same kind of paint, same kind of hairdress, and same kind of thoughts, if only they’d admit it. So it’s just like seein’ the chorus of a show go down the street. That’s why I say that the dames of the old Bowery days had it all over the women of today for originality, and looks too, for that matter. Am I right?’ [5]

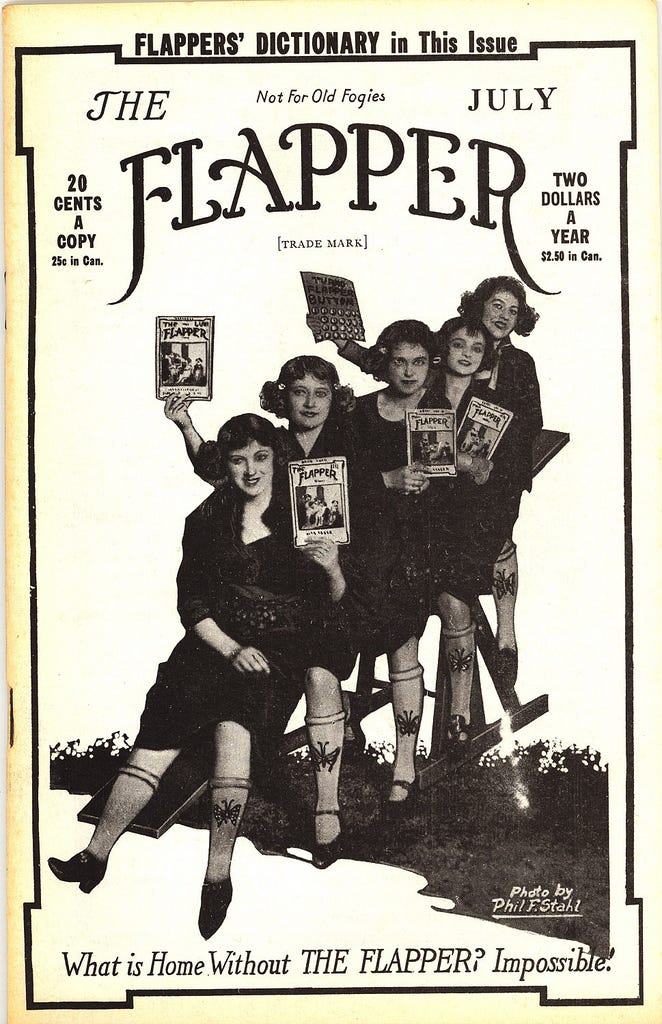

The larrikin’s donah, the coster’s best girl and the Bowery B’hoy’s g’hals had undoubtedly embraced slang, conversation would have been hard without it, but it was not their own: as their overall style, philosophy and preoccupations, it was that of their male companions; the flapper’s slang, as much as her rolled stockings, her shingled hair, her cigarettes and her petting parties, underlined how much her lifestyle reflected what would in time be called the generation gap but beyond that, her gender. That slang is not all her own work - though it appears that, quite at odds with the usual generation of slang, much was indeed her own work rather than that of her beau – and the line between flapper slang and contemporary college usage is hard to define, and there are inevitable overlaps with general usage, nonetheless a good proportion is something quite different to that of the wider world. Such talk, of which a glossary was compiled in 1922 and reprinted as ‘The Flapper Dictionary’ both as a short book and in a number of local newspapers, had its own themes. The flappers themselves, their boyfriends, the parties and dances they attended, the dancing and sexual activity they enjoyed (which latter appeared to stop short of intercourse, or certainly as regards descriptive slang coinages), drink, automobiles and so on. The over-thirties were barely mentioned, and if so, only with the brash dismissals of the young. Here at least Coughlin’s jibes cannot be denied: it is a vocabulary that voices ephemerality and hedonism and while some seems contrived, it flourished alongside its much publicized speakers.

The FLAPPER and Its DICTIONARY

The Flapper Dictionary, the contents of which were included with the first issue, in June 1922, of The Flapper magazine, its masthead proclaiming ‘Not for Old Fogies’, is an odd confection.[6] So too is the complementary list of ‘Flapper Filogy’ (a conscious mis-spelling that prefigures the far more extensive exploration of such orthographical games in the hip-hop era) that was compiled in 1927 by the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin and another list, under the rubric of ‘Judge Junior’s Dictionary’ and like today’s Urban Dictionary, compiled at least partially by readers, that came out in 1926 and 1927 in New York’s Judge magazine. The intention, as ever the case with specialist glossaries, was to help readers understand what they were meeting in the magazine’s pages, not to mention the world at large, thus permitting ‘the uninitiated’ to enter the magic circle.

Setting aside the terms they adopted, and looking at those for which the Dictionary is a first, and sometimes only example, flapper slang is perceptibly different to its mainstream equivalents. And by mainstream, it should be acknowledged that term refers to that bulk of slang that had been largely and traditionally coined by men. Groups of women had coined their own lexis, typically prostitutes, but flappers are the first to do so as ‘civilians’. Its pre-occupations are not all unique – the mainstream also notes physical attractiveness or lack of it, drinking and drunken-ness and of course wealth and poverty – but some are. It is often a matter of a new emphasis, a different point of view. That, for once, of a woman. Parties and dancing play a far smaller role in general slang; men are assessed there, but usually in terms of their own self-images and the cold light – veering between cynicism and pity – that flappers could cast on them is the reverse of the way the male mainstream dealt with such calculations. Marriage is the usual bad joke but in this case the laugh is on the groom and not the bride,

Flapper slang acknowledged sex, as we have noted, but only, it would appear, sex within limits: the physical exploration of petting, with its emphasis on kissing, but, as far as her language went at least, stopping short of intercourse. The harsh, unbridled sexism of male slang is wholly absent. Indeed. the aggression that underpins so much of male-generated slang is not for the flapper. In parallel, her slang seems to suggest a different class background. Male slang is gutter-upwards; flapper, that is female slang, seems far more middle class. This may be an assumption too far, but the flapper certainly lived a life some way beyond the usual slang-coining proles. She might not be a Zelda Sayre, but neither was she Stephen Crane’s fictional Maggie, ‘a Girl of the Streets’.

In retrospect and at the time, the flapper may have been claimed for feminism, but the magazine’s content gives little evidence. The ‘Monthly Chat’ column preached that ‘The Flapper stands for knickers’ (knickerbockers as used for sporty activities rather than any ‘naughty’ reference to underwear) and a story, ‘Class for the Thin: Slender, Lean and Slim’ was addressed to the ‘chiclets.’ (This may have been a reference to the popular brand of gum, but equally so, a diminutive of the centuries-old chick, itself shrinking chicken and now, if not perhaps then, seen as wholly demeaning). The magazine’s agony aunt signed her advice ‘Kewpie’, presumably in conscious reference to the kewpie doll of carnival stalls, traditionally won for young women by their boyfriends. Nor are references to the flapper’s female ‘sisters’ within the lists of her vocabulary especially charitable. There is no sense of sorority in *fire alarm, a divorcee or *fire bell, a married woman, only the sense that such supposedly predatory women represented a threat. (We must eschew slang’s uses of fire as venereal disease or the vagina). As for her own ambitions, it was every girl for herself. The *strike breaker, taking advantage of a *flat shoe, a lovers’ tiff, ‘goes with her friend’s steady while there is a coolness’. (She needed to get in fast, if the couple stepped on it, made up, she was out of luck). That this rendered her a sheba, snake or flamper, ‘a flapper vamp’ (vamp itself dates to 1915), mattered not bit; the nickname veal, i.e. a little cow, and one who ‘sets out to vamp with malice aforethought’, might have hurt.

Like the hippies of the Sixties, the flapper had no time for the over-thirties. Such oldies were *green apples (their disapproving, jealous ‘sourness’? their ignorance of flapper ways?) or *old fops. Older women were particularly scorned: the *bent hairpin, *covered wagon (who was fat too), or *face stretcher was ‘an old maid who tries to look younger’, while one who was seen as having given up that fight was simply a *rock of ages, i.e. ‘any woman over 30 years of age’. Her male equivalent was Father Time, first used in 1559 and, as the OED explains ‘conventionally represented as an aged man carrying a scythe and frequently an hourglass; sometimes also as bald except for a single lock of hair'. Her father was a dapper (presumably dad + flapper), and mother a wrinkle (surely the ancestor of today’s wrinklies, the old in general). Cruellest of all was Trotzky, an ‘old lady with a moustache and chin whiskers’; the goateed Bolshevik leader himself would have been termed a *Charlie or *whiskbroom.

Not that such old folk could be completely ignored. There were still chaperones: the *alarm clock, bidding flapperdom’s Cinderellas to cease their fun long before they might have wished, and the *fire alarm, dousing whatever current passions she was indulging. Actually talking to the old biddies seemed a man’s job. The *crumb-gobbler or *bun duster ‘an effete young man who attends smart tea parties and charms old ladies’ was of course nothing new, an earlier age would have termed him, less than flatteringly and equally suspicious of his sexuality, a jemmy jessamy; the *cake eater, ‘a Piker who frequents teas and other entertainments, without ever trying to repay his social obligations’, was possibly simply hungry.

RICH & POOR

Hunger was perhaps permissible, mean-ness was not. The Dictionary did not flatter the flat wheeler, ‘a young man whose idea of entertaining a girl is to take her out for an ankle excursion’ i.e. a walk (ankle as walk was another recent coinage) rather than ride, ideally in his sumptuous *cake-basket, his limousine (and both items bedecked in chrome). In fairness, he might simply be poor. He was also known as *Johnnie Walker (a tip of the hat to another liquor brand now forbidden by Prohibition). A *slip was a ‘one-way guy’: he took but failed to give back, as did the similarly despised *one-way kid, while the *Smith Brothers (punning on a slogan for America’s then best-known brand of cough drops) were those who ‘never cough up’. The finagler or phenogler played for time until a fellow-diner or drinker picks up a bill. The word borrows the verb finagle, originally dialect and meant to shirk or to fail to keep a promise. In 1839 a glossary of Herefordshire words explained, ‘If two men are heaving a heavy weight, and one of them pretends to be putting out his strength, though in reality leaving all the strain on the other, he is said to feneague.’ Like the chiseler (more usually a cheat), the *finale hopper was another cheapskate: as the cartoonist and word coiner TAD (T.A. Dorgan) put it, ‘a finale hopper is a jobbie [a diminutive of job: a type rather than modern Scotland’s term for a turd] who never takes a twist to a dance but who horns in on the last dance as the band is playing Home Sweet Home.’ It could also be applied to a man who was somehow never there when it came to paying his share of a bill.

Money itself was always important. Among the flappers’ terms were buffos and boffos, kale, dough, berries and jack. There were plenty of choices, maybe 70 others were coined in the period and of course hundreds predated it. If you were broke, then you were *on the stub which presumably referred to the fag-end of one’s funds, though maybe one’s comfortingly bounceable cheque-book. Your only hope was a *touchdown, a loan, which expanded on the 18th century’s touch and referenced the sheik’s on-field football prowess. More specific, and all the flappers’ own, was her take on *hush money, coined for bribes in 1709, but in her purse, an allowance from daddy. Whether it was meant to quiet her demands or offer him a sense of cross-generational philanthropy, who knows. *Mad money, also tweaked a known commodity. Rather than money for self-indulgent splurging, the more modern meaning, it was a stash carried by any sensible flapper out for the evening. She might need it for cab or bus if she was abandoned far from home by a boyfriend who tossed her from his car when she didn’t agree to sex; the ‘madness’ was his anger, though some might say her foolishness for accepting the ‘ride home’.

Some people had it, and flaunted it too. A *lamp-post was a particularly ostentatious piece of jewelery, the woman who wore it, usually some plutocrat’s wife or girlfriend, was a showcase (used for objects rather than people, since 1834) or billboard. *Darbs (from darby, meaning money since 1688) described ‘a person with money who can be relied on to pay the check’, otherwise known as a sugar daddy or butter-and-egg man (coined by the nightclub hostess Texas Guinan it meant a rich dairy farmer visiting the big city from the sticks: looking for fun and usually finding exploitation; Guinan’s invariable greeting, unsurprisingly, was ‘Hello, sucker!’). A fortune-hunter looking for a flesh-and-blood version of the California Gold Rush, was a *forty-niner. *Ritzy, from the luxury hotel, was another term for wealthy, though it could mean stuck up and snobbish, and as a noun, a flapper who aped a vamp: ‘black dress, jet earrings, black socks.’

PARTY TIME

If the flapper had know modernity’s party animal she would surely have embraced the term. Evelyn Waugh, looking back at London society from 1930 in his novel Vile Bodies, recalled a hyper-frenzied world of

‘Masked parties, Savage parties, Victorian parties, Greek parties, Wild West parties, Russian parties, Circus parties, parties where one had to dress as somebody else, almost naked parties in St John's Wood, parties in flats and studios and houses and ships and hotels and night clubs, in windmills and swimming baths, tea parties at school where one ate muffins and meringues and tinned crab, parties at Oxford where one drank brown sherry and smoked Turkish cigarettes, dull dances in London and comic dances in Scotland and disgusting dances in Paris’.

Memoirist he may have been, but Waugh’s fictive world was not especially productive of slang. Vile Bodies, set amidst the loucher end of the British upper classes, offers bogus, tight, whoopee (as a noun and meaning a party), the abbreviation N.B.G. (no bloody good) and the all-purpose suffix -making (‘The door opened and in came a sort of dancing Hottentot woman half-naked. It just said, “Oh, how shy-making,” and then disappeared’) but little else. This is doubtless accurate; in social terms, slang tends rise up, rather than trickle down.

The names and geography were naturally different across the Atlantic, but the atmosphere, as reported in gossip columns, high-circulation magazines and popular novels, was much the same.

Of all the era’s flapper coinages, parties and dances topped the list. The aim was to be invited but that never worried the determined. The era gave us the word crash (an abbreviation of crash the gate), to come in uninvited, the crasher and the crashing party. The young man who turned up from nowhere was a *walk-in. You danced to whangdoodle, jazz music, which was either echoic of the sound, or back-referring to a mythical beast, lurking on the wild frontier around the mid-19th century. Whether, given the jazz context, the ‘beast’ in question was black was unspecified.

Dance-bound you dudded up (from the 16th century’s duds, clothes) in your *urban set (a new dress) and dolled up in *glorious regalia. The whole process was known as *gandering, which seems to have come from French gandin, a dandy. It might include a visit to the *hen coop, the beauty parlor, though that had already served Brits as a brothel (1821) and US women students as a campus dormitory (1896). You abandoned your *false ribs (a corset), flattened your breasts with some kind of binding and unless your flawless complexion rendered you *waterproof, in which case the process was un-necessary, readied yourself for the evening’s battles with a coat of *munitions (the synonymous war paint was 60 years older), basically powder and rouge, making sure to avoid an *overdose of shellac, too much of a good thing, or at least of powder: no one wanted to be branded a *flour lover. As for the boyfriend, the ideal type seems to have been the *Brooksey Boy, one who is dressed at New York’s then epitome of preppie style, Brooks Brothers.

The dance was a blow (first used at Harvard in 1827), a wrestle or a struggle, which upped the ante on the earlier bun struggle, the somewhat more genteel tea party otherwise known as a bun-rush, bun and sandwich scuffle, muffin-struggle or tea-scramble. If it was out of town it was a dragout and in either case, the girl of a couple was a drag (as in taken along and borrowed from the campus). Dancing itself was button shining (very close, and such cheek-to-cheek gyrations were known as *giving the knee), *dragging a sock or shaking the rug. A good dancer was a *rug shaker, a boy or ‘a girl addicted to shimmying’, a *hot foot or hot sock, an *Oliver Twist, a stepper, *hopper (boy) or *sip (girl). A large male was a *scandaler, or as the glossaries put it, ‘a dance floor fullback. The interior of a dreadnaught hat, Piccadilly shoes with open plumbing, size 13.’ A *sharpshooter didn’t just dance well but splashed his money around; a dance-mad boy was a*floorflusher or *sap. If he was eying up the refreshments over your shoulder he was a hoof and mouth. Their flapper equivalent was a *sloppy or a *beazle or beasel, which suggested a certain sexual precocity known as vampishness, and which made him a *beasel hound. Flapper-world also coined *tomato for an attractive girl, but the Dictionary modified her as a ‘good looking girl who can dance like a blue streak, but is otherwise a perfect dumbbell.’ Bad dancers included the feet, the heeler, the cluck (dull and stupid ‘the brains of a chicken’ since 1906). A boy who trod on your feet or dogs was a *corn shredder or *horse prancer; your *dog kennels, shoes, would never be the same.

It was not mandatory. Some girls were bashful and dancing with them was known as getting the *absent treatment. And just as the chaperon persisted, so too did the wallflower (coined 1819), known unsympathetically as a *cancelled stamp or a *dud (coined a century earlier in Scotland for a ‘thowless,’ i.e. spiritless man). Worse still was the dumbbell (1858), not just a wallflower but stupid with it. Nor did everyone even want to go out. The rug hopper, parlor hound or parlor leech stuck to staying home, playing the gramophone for music. His similarly domestic partners were *ground grippers, *gussies (hitherto meaning a gay man), *Priscillas or *wooden women, none of whom wanted to go out partying. Nor did everyone want the middle-class social whirl; there were other allurements, notably the bohemian world of Greenwich Village where ‘artistic’ studio parties – dago red and spontaneous poetry – welcomed slummers, even if the word had emerged in 1887, describing a less hedonistic form of class voyeurism.

DATING / RELATIONSHIPS

Clothes and hairdo aside, if anything differentiated the flapper from her predecessors it was sex. The calculatedly buxom Gibson Girl of the 1900s, all whalebone, big hats and décolletage, may have fuelled male fantasy, but if she put flesh on dreams she wasn’t talking (though Mae West, for whom she remained a role model, was vastly loquacious). The flapper was consciously outrageous. Or so she told the world. Contraception was more easily available, but while she was unashamedly happy to indulge in modernity’s ‘slap and tickle,’ it’s hard to tell whether what the Dictionary defined as ‘love-making’ was what we term making love. She was seen as sexy, but there is a far stronger sense of playfulness and experimentation. So far, but no further; kitten but not yet cat. However much she wished to upset her ‘Victorian’ mother, that mother had still brought her up and instilled an older set of values. In Elinor Glyn’s Flirt and Flapper dialogues of 1930 the Flapper shocks her ancestor with tales of hands-on exploration, but beyond that she can only resort to an evasive ‘er…’. Neither great-grandmother nor readers ever discover quite what ‘er…’ may imply though the former is keen to find out. Perhaps the clue lies in the era’s primary term for such enjoyments: petting, carried out at what Scott Fitzgerald in 1920 termed ‘that great current American phenomenon, the “petting party”,’ a phenomenon that today seems somewhat structured. For instance etiquette permitted postponement. One could ask cash or check? which meant ‘do we kiss now or later?’, and if the answer was check, the intention was to mark some kind of sexual dance-card and get back together at a later stage. But petting, even if it reached the stage of what the Beatles so memorably termed ‘finger pie’, does not equate with intercourse.

You set up your date – *book-keeping – and the first job was to *Houdini (named for the famous escapologist) out of the parental house. Then unless either partner were a holaholy, a prude, and declared *the bank’s closed, which meant nothing doing, the games were on. She was a biscuit, a ‘pettable Barlow or Beasel, a game Flapper.’ He was a *snuggle-pup or -puppy. If he was a smooth talker (if such time-consuming seductions were even required) he was a big timer, defined as ‘a charmer able to convince his sweetie that a jollier thing would be to get a snack in an armchair lunchroom’ or to put it another way, ‘a romantic.’

They were both smudgers (from the older smoocher), neckers, cuddlers (a cuddle-cootie liked to do it in cars), and of course petters. What they did was lollygag, which gave lollygagger, ‘a Bell-Polisher addicted to hallway spooning.’ (A bell polisher was the sort of young man who turned up in the early hours, leaning on the apartment bell). Alternatively the words were *barneymugging or just mugging. The first seems to mix barney (1859), a jolly social party, and mug, to kiss (1821). Kisses were rated; no-one wanted a *cherry smash, a half-hearted effort. Nothing was certain. He might be goofy, stuck on her, but that still didn’t save him from the icy mitt (1898), and being given the air. She might, after all, have fallen prey to a weasel (1624), a ‘girl stealer’. Even worse he might be streeted, tossed out of the party. In turn he might toss and hike: tell her goodbye and set off to look for something better. Either way, someone was going to be *grummy, perhaps from grumbling and meaning depressed. On the seemingly rare occasion that flapper opted for a long term relationship, she was known as a *monog; the term worked for the boy too. If they were engaged the boy was a *police dog, presumably another put-down: he followed you around and offered (unnecessary) protection.

SHIFTERS & SHEIKS

Perhaps it was through her role as coiner of the lexis, that the flapper found fewer words for girls than boys. She could be a *flap, a *barlow, a *shifter and although Mencken’s encomium claimed otherwise, a chicken. The shifter was defined as a ‘grafter,’ but whether that means hard worker or con-woman (both slang senses) is hard to discern. One theory has linked Barlow to Marie Barlow, a popular cosmetics brand of the era; slang’s eternal punning would suggest a tie-in to the widely sold Barlow knife, because she’s ‘sharp’. If she was a weed, she was a girl who took risks, though the reason is obscure. She could be a jane, with its slightly noirish-overtones, though the Dictionary terms her ‘a girl who meets you on the stoop.’ This presumably implied the flapper’s rejection of the parental grilling of her beau that represented part of the traditional dating ritual and took place in the parlor, while somewhere upstairs she primped and prettified. (It might also have used Jane as generic for a servant girl, forbidden to meet her boyfriends in the house). She aimed for meringue, personality (presumably light and frothy) and swanned rather than simply walked.

Somewhat oddly, the Dictionary, published in 1922, does not mention sheik, for all that it has become the flapper’s male antonym as far as history has decided, and gave only such derivatives as sheiky, sheiked out, and sheik oneself up. It came from E.H. Hull’s prototype bodice-ripper The Sheik, published in 1919, then vastly popularized by the 1921 movie starring Rudolph Valentino, either ‘Latin lover’ or ‘pink powder-puff’ according to taste, or more usually gender. It was perhaps Valentino’s ambivalent image that had the Judge’s glossary define sheik not as a male flapper, but as a ‘male vamp.’ Perhaps sheik was ambivalent too; a little over-exotic: the Dictionary, and many other sources, opted for the jocular flipper. It can already be found in 1905 and was common in flapperdom’s heyday. As a boyfriend he was a goof, more usually found meaning fool and as such suggesting the flapper’s cool assessment of her beaux. He could also be a high-john or highboy, a sweetie or cutie (these latter a reversal of the usual male-to-female christenings); his blue serge, which points once more to Brooks Brothers tailoring. Slat, elsewhere meaning ‘rib’ may or may not offer another role reversal, on slang’s own use of rib, meaning wife. His innate disposability is reflected in umbrella, who could be used when convenient, folded up and tossed aside. The rainy weather that was implied presumably meant a lack of more attractive partners.

On the whole the flapper was quite disdainful of her male equivalents. The dewdropper, either rich or lazy, did not work, and slept all day (its origins lay on campus where it was seen as a grudging compliment but the energetic flapper would not have been impressed); the dingle dangler would never stop telephoning (a possible link to the 18th century dangler, a suitor, but we shall assume that the flapper had missed a contemporary usage: the penis); the punning mustard plaster (coined in a British music hall song and thus a rare import) was ‘an unwelcome guy who sticks around’) and the pillow case a young man who is ‘full of feathers’, feathers abbreviating horse-feathers which in turn euphemized the earthier horseshit. The flapper was doubtless aware, and it was one of her very rare approaches to actual obscenity. The potato was stupid, the monologist a young man who hated to discuss himself and a blushing violet one who resisted attention. The assumption for these latter pair is somewhat heavy-handed irony. No irony was required for the lens louse, though it did tweak the usual use, one who monopolizes the camera into one given to monopolizing the conversation. A smooth, too smart for his own good, failed to keep his promises. Perhaps the oddest, at least chronologically, was wally, defined as ‘a goof with patent leather hair.’ Given wally’s subsequent career in slang this may be assumed to be derogatory, but the possible origin, Italian guaglio, a boy, may give a somewhat racist clue to the focus on grooming. Finally one has the drugstore cowboy, and cowboy alone, ‘a young fellow who doesn’t pay much attention to girls.’

MARRIAGE / DIVORCE

If their world joined those other things that could not survive the Wall Street crash of 1929 – we hear very little of flappers other than as a historical curiosity after that – it has also been suggested that by then she had grown up and surrendered to domesticity. Yet if the flapper did get married it was surely after trying all the alternatives. Her take on the institution was far from positive, in slang terms it fitted almost perfectly with the traditionally skeptic male view. He might call her his storm and strife (a variation on the UK’s original trouble and strife) but ‘obey’ didn’t seem to be part of her version of the wedding service. To be engaged was to be insured, which sounds like a sensible economic approach: certainly love didn’t enter the calculation; but the deal soon soured and marriage itself was an eye-opener, i.e. a nasty surprise, the ring a manacle or handcuff (the feeling was mutual: ball and chain for a wife or girlfriend was coined almost simultaneously, in 1924) and a divorce was a *declaration of independence. To secure a divorce was dropping the pilot, echoing Tenniel’s famous cartoon of Bismarck’s departure from the helm of German politics) and once divorced a woman was *out on parole. She was not unconditionally free: one might, she accepted, fall for the same old snares.

FOOD/DRINK

The flapper liked her liquor. That it had been purged from the national digestive system by the 18th amendment merely gave it extra oomph. To drink was to lap (which went back to 1819); throwing it back was all great fun and in the spirit of things she called it slightly jokey names such as alky, jazz water, joy juice, giggle water, tonsil varnish, hooch and of course good old booze; the era came up with 100-plus coinages. To be drunk was to be feeling no pain, over the line, shnockered, cooked, laid out, embalmed, shellacked and hundreds more, among them half-cut (1802), jammed (1844), soaked (1852) and shined (1900).

The man who supplied the goods was an embalmer (embalming fluid had meant rotgut whiskey since the Civil War) or a legger. The cellar-smeller had started life as a prohibition agent, but for flappers he was a young man who made sure he was always around when free liquor was handed out; he was probably a punch rustler too, one who hung around the party’s drinks table. Both were almost certainly armed with luggage, a hip flask. Noodle juice, which was tea, stood out against the alcoholic parade, but whether the noodle meant a fool, or whether it was the head and the liquid thus brain food, is unknown. She ate, and a restaurant, though they don’t seem to have played anything like the role of speakeasies (the bar proper being in legal abeyance) was a nosebaggery. This drew on the late 1890s nosebag, a hotel or lodging-house, and the older put on the nosebag, which had meant to eat hurriedly, sometimes even as one worked, since around 1870.

That the flapper drank was bad enough, that she compounded it with smoking may have been even worse. For those who assessed such things, both were the unarguable badge of the loose woman. The flapper could have cared less. Much less. She enjoyed her ciggy (1912), handed round the pack, the hope chest, and punned it as a lip stick (stick for cigarette was about 20 years old). Once consumed the remains were a dinch or dincher. Those who begged cigarettes from others were grubbbers (it had meant a plain beggar since 1772) and a heavy smoker a smoke-eater. Cigarettes also lay behind the –me coinage as a way of asserting a demand. The locus classicus would come in the film The Sweet Smell of Success (1957) where the venal columnist J.J. Hunsecker confirms his absolute power over the submissive, scrabbling press agent Sidney Falco with the command, ‘Match me, Sidney,’ i.e. Light my cigarette. But the flapper had been there first,

WALK / TRANSPORT

She was a girl on the move and urged her companions, let’s blouse, which may have come from let’s blow and both meant time to hit the road. Ideally via limousine, but she acknowledged the dipe ducat, a subway ticket, the stutter bus which meant a truck and, presumably in smarter circles, the stutter tub which was a motor-boat. Failing a limo the vehicle of choice was dimbox, i.e. a taxicab, its ill-lit backseat doubtless useful for the inevitable petting. If all else failed one could even ankle.

TALK

Feathers, as noted, meant idle chat, and there was plenty of that. To talk thus was to *punch the bag or *spill an earful and such *low lid (i.e. the opposite of ‘high brow’) chit-chat was also known as *static, although not yet accompanied by its overtones of argument and irritation, *oatmeal mush (the spiel of choice for a voluble cake-eater) and chin music (1821). Everyone liked a gossip, known as *prickers or clotheslines (the idea of negative if fascinating information as dirty laundry had been around since 1863), but if gossips turned gimlet, a chronic bore (another flapper pun), the cry, even if was 40 years old, was pipe down! To Edison was to subject to interrogation while a bean picker was emollient figure; patching up wobbly relationships and ‘picking up spilled beans’. Boasters were false alarms (1902) or wind-suckers (which went back to the 17th century).

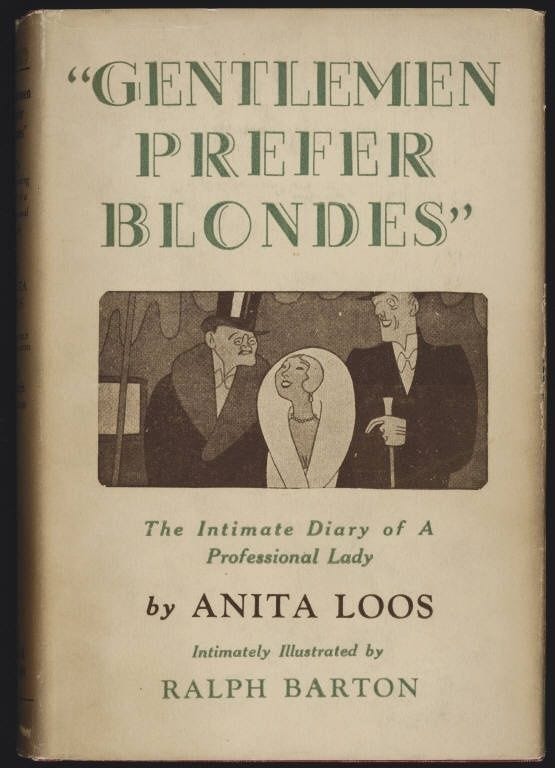

Flapper talk was liberally laced with exclamations. Some were all her own work: for crying out loud! (a euphemism of for Christs ’sake!) *check your hat!, *nerts! (as in nuts!, nonsense!), *not so good, *di mi! (i.e. dear me!), *woof! woof! for ridicule or indignation, *rhatz!, which was the older rats! with added orthography and a very modern ‘z’, and *you slaughter me! which had been around as ‘you kill me’ since 1881. There was also *I should hope to kill you! More violence was on offer with variations on knock or knocked for a row of…ashcans, ...flat tires, ...latrines, ...Mongolian whipped cream containers, ...Portuguese flower pots, ...red-headed Riffians, ...shanties, ...shitcans, ...silos, ...sour apple trees, ...stars, and ...totem poles. The imagery seemed, logically enough, to have emerged from the recent world war. Still destructive, she liked to break things down with sounded, if not actually spoken hyphens: ab-so-lute-ly , pos-a-lute-ly and pos-i-tive-ly. And how! Others, coined elsewhere, included it's the bunk! (1893), zowie! (1902), hot (diggety) dog! (1906), ’stoo bad and oh yeah! Finally there was a creation plucked from Anita Loos’ Gentlemen Prefer Blondes of 1927, wherein the heroine Lorelei Lee, a showgirl rather than an actual flapper, noted ‘When I went up yesterday to meet she and Major Falcon for luncheon, I overheard her say to Major Falcon that she really liked to become intoxicated once in a “dirty” while. Only she did not say intoxicated, but she really said a slang [word].’

Ms Lee’s reticence seems – though the slang word was far from necessarily coarse – to have been echoed by her flapper contemporaries. If one lexical style differentiates their slang from that of the male contemporaries it is its ‘cleanliness’. Or, one can never be sure, the seeming absence of recorded obscenity. She remained, in this at least, her mother’s daughter. She may have replaced soap and water with paint and powder, but its threat still lingered for a ‘dirty’ mouth.

GOOD & BAD

The flapper was definitely judgmental. If she encountered offensiveness, whether in person or circumstance she fought back. Not for her the sniveling self-infantilism of ‘micro-aggressions’ and the cringing ‘safe space’. She had an identity, she needed no accompanying politics.

Let us ponder her admiration first. Cat’s pyjamas (or pajamas), along with bee’s knees probably the era’s best-known term for excellence, is so far first recorded in 1918 and credited to the cartoonist T.A. Dorgan, known as TAD and, like Oscar Wilde before him or his contemporary Dorothy Parker, credited with most of the funny lines that emerged at the time, and especially in TAD’s case the slang. That said, he seems only to have used ‘the cat’s’ and that in 1923; our current first use comes from the journal Dialect Notes, and no source is offered. In addition, the format may not even have begin in America. Australia’s slang-dense compilation known as ‘Duke Tritton’s Letter’ is thought to have been published in 1905. It runs, in part, ‘I’m teaching Mary and all the Tin Lids in the district to Dark An’ Dim, and they reckon I’m the bees knees, ants pants and nits tits all rolled into one.’ However Tritton’s missive may have appeared later, though still prior to 1918.

But if the flapper did not coin the phrase that she used so often, then she undoubtedly popularized it and elaborated upon its potential. Among its variations, then and later, are: the cat’s meow and cat’s particulars, the frog’s eyebrows, goat’s whiskers, duck's quack, bee's knees, kitten’s ankles, monkey's eyebrows, bullock’s bollocks, cuckoo’s chin, duck’s nuts, elephant’s (fallen) arches, elephant’s manicure, gnat’s elbow, nit’s tits, owl’s bowels, snail’s ankles, hips or toenails, turkey’s elbow, and turtle’s neck. As the lexicographer Tom Dalzell, in his book on teen slang, Flappers to Rappers, explains, ‘whatever the origin [of the phrase] the same enthusiastic praise garnered by cat’s pajamas was conjured by the combination of practically any animal and any part of its anatomy.’ He then lists some 42 terms.

Two other words, even if coined at other hands, were much loved. One was lallapaloosa (first recorded in 1881 and variously spelt as lalapalooza, lalapazaza, lalaplunko, lalapoloosa, lalla, llallapalooza, lallapaluza, lallypaloozer, lolapaloosa, lolapalooza, lollapaloosa, lollapalooza, lollypalooza, lollypaloozer, wollapalooza). It was defined as something or someone outstandingly good, stylish or pleasing of its kind. The other being copasetic. If lallapaloosa had problems with its spelling, then copasetic was not to be outdone, with: copa, copasetic, copasetty, copesette(e), copissettic, copus, kopacetic, kopasetic, kopasetee, kopasette. It has yet to find an unimpeachable origin. Among the suggestions are the Chinook jargon copasenee, everything is satisfactory, especially as first found on the waterways of Washington state. Others include: (i) the painfully contrived phrase ‘the cop is on the settee,’ i.e. the cop is not paying attention, which elided into copacetic and was supposedly used as such by US hoodlums; (ii) a word presumed to be Italian but otherwise unknown; (iii) French coupersetique, from couper, to strike; thus striking or worth a strike; (iv) the Yiddish phrase hakol b’seder, all is in order or, earlier, kol b’tzedek, all with justice. We are perhaps best advised to dismiss the lot and accept the dictionary’s dour, but safe declaration ‘etymology unknown’.

On the whole the flapper’s approval was directed at boys (which makes change from her generally skeptical, even jaundiced eye). The good-looker could be tight or airtight, his style could be klippy, i.e. neat, and his clothing ducky (first applied to a moustache in 1851 Australia). Other positives included the berries (1908), keen (1899), nifty (1865), swanky (1846), swell (1812), tasty (1788) and the real McCoy, which evolved in the early 20th century. Perhaps the most interesting is unreal, a term that would not reappear until the 1960s, and then used by Australian surfies.

As for negatives, they too hit out at items and individuals. The great cover-all was the mysterious (to us) *seetie, ‘anybody a flapper hates.’ Its etymology defeats modern research but might this be a rare example of flapper obscenity, taking seetie as ‘C.T.’ and thus, in the widest sense, ‘cockteaser’, coined quite recently in 1890?

Much was nonsense; blooey (1910), fluky (910), apple-sauce (1884) and which perhaps comes from an old minstrel show joke, based on the problem of dividing 11 apples equally among 12 people and horses: the answer, one makes applesauce. There was baloney (1885), banana oil (1925), bunk (1893), blah or blaah (1918) and hokum (1908). There was dumb, which applied to people as well as objects, ideas or places, punk (1904) and a lob, which originally described a useless racehorse but for flapperdom meant a waste of time.

For individuals the greatest crime seems to have been stupidity. One might be a dumb dora (another alleged TAD-ism), a *bozark (from bozo, a fool), an egg (1917), a dumb-bell (1858), or a dumkuff, from the German dummkopf and found as the literal dumb-head in 1887. An oilcan was ‘an imposter’, not necessarily stupid, even ingratiating (oil had long implied verbosity), but lacking real social grace. And lack of brains segued into lack of social skills, making one a *wurp (perhaps from twerp), a *boiler factory, a dud (1825), a *gobby, usually meaning over-talkative, was defined as a ‘Dumbell who has no style, no pep, no nothing.’ Those who thought too much of themselves were *high hatty (which came from contemporary vaudeville where a topper, symbolic of prestige and wealth, was known as a high hat), grungy, envious and perhaps from grudge, and upstage (1901). After that an *airedale, a ‘homely man’ and which seems to render the long-established dog more specific, almost kind.

Finally came the outside world, the realm of the nay-sayer and the censorious. They, represented those in authority or power, the Establishment. The pronoun, as the Dictionary added, was ‘used by Flappers with tone of disgust to denote the older generation.’ They provided the crepe hangers, the killjoys (1776), the pills (1830), the wet blankets (1810) and the *slapper who presumably slapped down one’s enjoyments. The outside world went further: beyond the city. Being, at least at her birth, an urban creature, the flapper had little time for the peasant. Not enough time even to coin any new descriptions; the country folk, stupid and dull by default, were *bush hounds, brush apes (1913), apple knockers (1913), hicks, hay-shakers and country jakes. They were beyond her pale. They were not her problem.

A WORD of HER OWN?

Do not trust the dictionary, especially when, as for too much of our knowledge of flapper-speak, that lexicon must fall back on no more than three random glossaries, culled from and perhaps created for the newspapers and magazines that featured them. If they are relatively consistent, then one senses simple plagiarism. The core list appeared in The Flapper, was immediately disseminated through America’s network of small-town papers, and pretty much remained the authorized version. We are lost for the vital information: who assembled the lists, who or what (books, magazines, movies?) were their sources, was there any field-work? And beyond that, one step nearer the ‘truth’, who coined the words in question.

[1] S. Lewis Babbitt (New York 1922; 1974) p. 258

[2] the illustrator Edward Gorey also went back to the ‘classic’ flapper when drawing a vamp in a number of his books, typically the sexually adventurous but ultimately unfortunate ‘Alice’ of The Curious Sofa (1961)

[3] Mackrell op.cit. p.11

[4] Mackrell op.cit. p.5

[5] Chicago Evening American Feb. 1929 q. in Louvish op.cit. p.163

[6] of the terms that follow those included in the Dictionary are preceded by an *

Fabulous. Thank you.