[Impelled, not to mention impressed by Nancy Friedman’s study of beasel (here), I checked my 2019 book Sounds and Furies (orginal title Bitching - don’t ask) and disinterred what I had to offer vis-à-vis The Flapper in the context of her language. There is a whole chapter, and I have broken it down into three posts. A good deal, I acknowledge, but worth it, I hope, for what stands in my opinion as the first ever unarguably women-coined slang.]

********

She’s independent, full of grace, A pleasing form, a pretty face; is often saucy, also pert, and doesn’t think it wrong to flirt; knows what she wants and gets it too; receives the homage that’s her due; her love is warm, her hate is deep, for she can laugh and she can weep; but she is true as true can be; her will’s unchained, her soul is free; she charms the young, she jars the old, within her beats a hearty of gold; she furnishes the spice of life — and makes some boob a darn good wife!

‘Our Definition of the Flapper’ in The Flapper magazine vol. 1 June 1922[1]

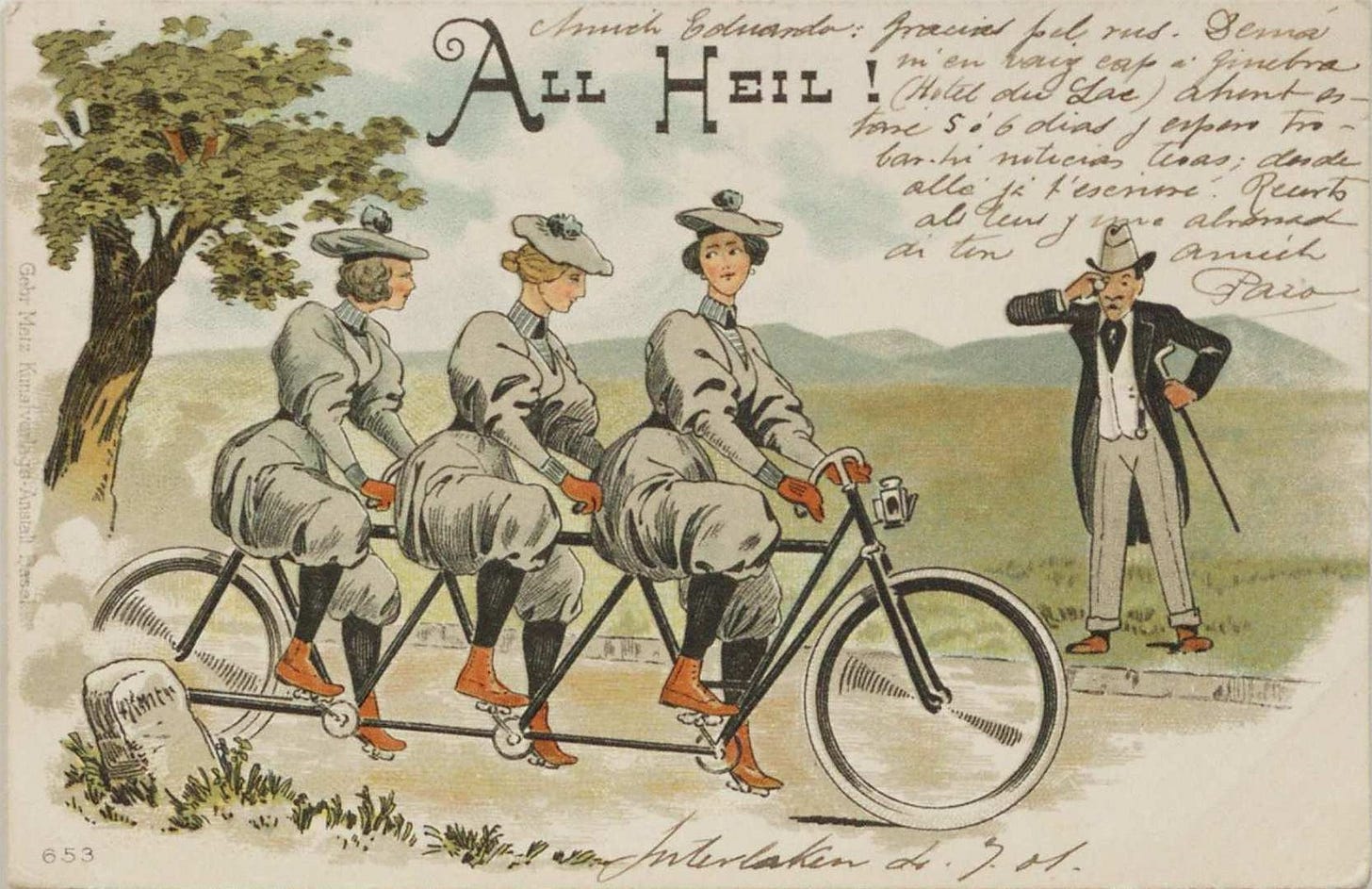

The flapper of the 1920s, whose moment in the sun paralleled what was typically termed the ‘roaring’ Twenties and the ‘Jazz Age’, may be said to embody the first ever ‘youth cult’. She had all the necessary kit: an unashamed exploitation of the generation gap (a concept, like ‘youth cult’ that would not enter the language for another 40 years), an immediately (and to many disturbingly) identifiable uniform that was all her own, a lifestyle and a language that she had created. She both shocked and delighted that vital ingredient of every such cult: an attendant media, who gleefully pursued her, whether to celebrate or condemn. Then there was one final and wholly unprecedented fact: above all else, the flapper was she.

The FAST GIRL

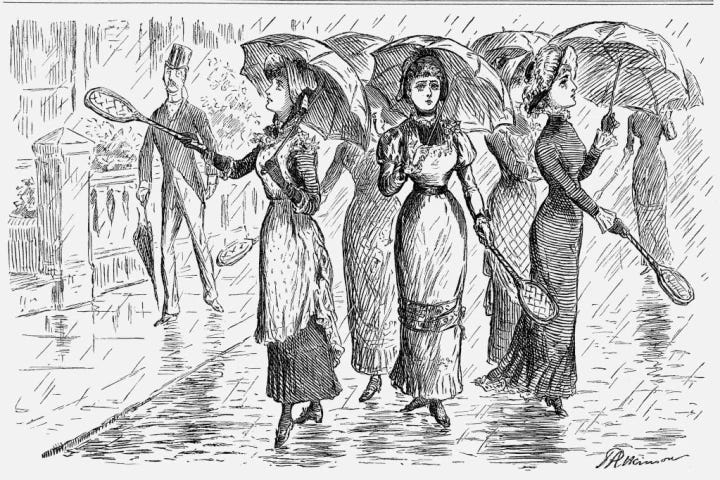

Nothing, even such a trail-cutting, quite possibly revolutionary social movement emerges without precedent. Thus the mid-19th century had witnessed the emergence of what might be termed the prototype flapper: the ‘Fast’ Girl. Her use of slang had been one of her identifying characteristics, and she was more happily independent than her mother (and society at large) might have desired, but her characterization seems to have been from the outside in and while commentators clamoured to analyse and (usually) condemn her, she did not self-identify.

The idea of fast in the context of lifestyle seems to appear in the very early 18th century. (Given its sense of movement it is the antithesis of those slightly earlier senses based on holding fast, i.e. stasis[2]). The use is not dissimilar to slang’s flash, but the female varieties, flash piece and flash woman, cut straight to whoring. Quoting Dryden on ‘The Good Parson’ – Of Sixty Years he seem'd; and well might last / To Sixty more, but that he liv'd too fast – the OED (in an entry composed in 1895 and as yet unrevised) defines the phrase live fast as ‘to expend quickly one's vital energy’ and in a second sense ‘to live a dissipated life’ quotes one of slang’s favourites, Dryden’s contemporary Thomas Brown, a popular satirist (and allegedly the first to place blanks in proper names so as to escape threats of libel, e.g. Mr J— G— ). Brown notes that by ‘living very fast’ a man ‘had brought his nobles [i.e. 6s 8d, and thus half a mark or one-third of a pound] to nine-pence’ [just under one-ninth of the original value]. That fast might be paired with woman, girl or, as the media seemed to prefer, young lady, was acknowledged, even if the original OED had only a single citation, dated 1856. ‘As applied to women’ it referred to those considered ‘studiedly unrefined in habits and manners, disregardful of propriety or decorum’. It was still sixty years premature, but it might equally well have served the flapper.

The lexicographers were running slow: the phrase and the concept of ‘the fast young lady’ was hard-wired into the lexicon of disapproval by the mid-19th century. Hotten, defining it for his slang dictionary of 1859, showed that the term played by the usual male-female double standards: ‘A fast man – a person who, by late hours, gaiety and continual rounds of pleasure, lives too fast, and wears himself out [...] a fast young lady is one who affects mannish habits, or makes herself conspicuous by some unfeminine accomplishment, – talks Slang, drives about in London, smokes cigarettes, is knowing in dogs, horses, &c.’[3] A year later the Saturday Review explains the fast woman as one ‘who has lost her respect for men, and for whom men have lost their respect also.’[4]

Neither definer notes class, but that was there too. Working-class women were not fast. They might be just as hedonistic as their wealthier, better-born sisters, but had the idea existed, they could not be seen, unlike the latter, as class traitors. Working class girls, after all, weren’t meant to have standards. The middle and upper class young lady was, and thus their betrayal of such standards – their failure to emulate their ‘slow’ sisters (slow being defined by slang as unfashionable, dull, lifeless and insipid) who did not smoke, did not drive around London (quite possibly unchaperoned), did not offer her expert knowledge of horseflesh or hunting packs and perhaps most important did not talk slang – was all the more reprehensible.

The identification of fastness with non-standard speech seems to have been worldwide. In 1871 Tom Taylor (who had talked in another script of ‘The “horsey” woman of fashion, who lisps slang as easily as French’[5]) put on New Men and Old Acres and in the play characterizes a rebellious young woman as ‘dreadfully addicted to slang’.

In 1862 the Melbourne Punch offered a series of ‘Sketches of Society’. Among them was: ‘The Fast Girl’:[6]

The fast girl is a ‘gent’ in petticoats, a connecting link between the two sexes, and exhibits some of the most unattractive qualities of both. Her voice is loud, her utterance voluble, and she has a copious vocabulary of slang at her command, upon which she makes large and frequent draughts. She has neither the modesty nor the winsomness of womanhood. She affects masculine pastimes, smokes cigarettes on the sly, and goes the pace furiously in dancing, when the centrifugal tendencies of her skirts give her the appearance of a ballet girl on the stage. At such times she is as flushed as a Bacchante, and, in the wild disorder of her spirits, might pass for one. On occasions she can tipple, and has been even known to talk incoherently and to be unsteady in her gait. She excels in ‘chaff’ and is proud of the accomplishment. In conversation she is loud and confident, ‘stiff in opinions,’ and is uneasy if she does not succeed in drawing the eyes of the whole company upon her. She knows a little of everything, and vents her observations with an entire disregard of their crudity. She has a predilection for novels of the French school and for erotic poems. She is positive in assertion and abrupt in contradiction. She cultivates a taste for sarcasm, and has no mercy on the reputation of even her dearest friends. She aims at saying smart things, and faintly resembles Lady Mary Wortley Montague, minus her wit, her ability, and her tawny linen.

If nature had made the fast girl a man, the creature would have been a fluent stump-orator or a knowing horse-jockey, or a lively Merry Andrew, or a dissipated pleasure-seeker. As it is, she possesses some of the most offensive characteristics of the gent, but none of the graces of a lady, nor the charms of a woman. She votes the more feminine heroines of Shakspere [sic] ‘slow,’ and speaks contemptuously of the few genuine gentlewomen to be met with in society.. The gracious dignity, the sweet repose, the fortifying self-respect, the delicate courtesy, innate gentleness, modest reserve, and moral elevation of the perfect lady , she can neither comprehend nor admire – therefore she depreciates and dispraises them. If she marries from affection the chances are that she will ruin her husband by her extravagance, and persecute him with her jealousy. If she marries for a settlement, she will degenerate into a married flirt, or subside into a confirmed tippler. In any case, she is pretty sure to be both fast and loose.

The press vied to condemn her. ‘Fast girls’ were ‘masculine hoydens—boys in petticoats, who flavor their conversation with slang, call their male friends by their abbreviated Christian names, or by their nicknames, and who are simply despicable as vulgar Amazons, or brazen flirts.’[7] They were ‘the wildest, pertest, rudest, and most viciously impudent animals yet ever met with, their brothers having been their principle companions, they swear like hovelers of a seaport town, and are perfect adepts in the slang of the day.’[8] They were nothing good.

The American lexicographer Schele de Vere, whose Americanisms appeared in 1872, saw the problem as rooted in the foolish fashion of permitting women to say what they wanted, which license included the use of slang:

‘American cant and slang have some peculiarities unknown to the old World. The women even contribute to it largely, availing themselves of the national gallantry extended to their sex on all occasions, for the purpose of indulging to the utmost in unbridled license of expression, both in public and in private. There is as much truth as wit in the conundrum: Wherein do the women of the day resemble St Paul? In that they speak after the manner of men.’[9]

Slang, as the clips suggest, was their primary sin. Taylor’s pert young heroine may have justified her off-piste vocabulary and challenged her mamma’s disapproval by claiming that ‘men like it’, but the leader-writers were far from appeased. Australia seemed especially perturbed. Thus the Sydney Mail in 1871:

If it is necessary that any one in the family should [talk slang], let your big brother, though I would advise him not to talk ‘Pigeon English’ when there is an elegant systematized language that he can just as well use, but don’t you do it. You have no idea how it sounds to ears unused or averse to it, to hear a young lady, when she is asked to attend some place of amusement, answer — ‘Not much;’ or if requested to do something she does not wish to— ‘Can’t see it!’ Not long ago I heard a Miss, who is educated and accomplished, say in speaking of a young man, that she intended to ‘go for him!’ and when her sister asked her assistance at some work, she answered, ‘Not for Joe!’

Now, young ladies of unexceptionable character and really good education, fall into this habit, thinking it shows smartness to answer back in slang phrases ; and they soon slip flippantly from the tongue with a saucy pertinence that is not lady-like or becoming. Young men who talk in that way do not care to hear it from the lips they love or admire. It sounds much coarser then. And really, slang does not save time in use of language, as an abbreviation. No! is shorter and more decided than ‘Not much.’ And I am sure, Yes! is quite as easily said as ‘I’ll bet.’ More than one promising wedding has been indefinitely postponed by such means ; for however remiss young men may be themselves, they look for a better thing in the girls of their choice, and it does not help them to mend a bad habit to adopt it too.

It was axiomatic that ‘the loud, confident, slang-loving, fast-living women of fashion [have] unfurnished heads and vacant hearts.’[10] The over-riding inference: unfettered immorality: another paper savaged a well-known beauty: ‘she knows as much slang as a cabman; she drinks as much as a fish... she gambles like Fox and Sheridan together ; she wears a dress which the French police would exclude from the Jardin Mabille.’[11]

Yet she had her defenders. In 1860, at the height of the moral panic, The Inquirer of Perth, Western Australia, offered a cheeky and supposedly first-person summing-up – in verse[12]:

FAST YOUNG LADIES.

Here's a stunning set of us,

Fast young ladies;

Here's a flashy set of us,

Fast young ladies;

Nowise shy or timorous,

Up to all that men discuss.

Never mind how scandalous.

Fast young ladies.

Wide-awakes our head adorn.

Fast young ladies;

Feathers in our hats are worn,

Fast young ladies;

Skirts hitched up on spreading frame.

Petticoats as bright as flame,

Dandy high-heeled boots, proclaim

Fast young ladies.

Riding habits are the go,

Fast young ladies;

When we prance in Rotten Row,

Fast young ladies;

Where we're never at a loss

On the theme of ‘that ’ere ’oss,’

Which, as yet, we do not cross.

Fast young ladies.

There we scan, as bold as brass,

Fast young ladies,

Other parties as they pass,

Fast young ladies;

Parties whom our parents slow.

Tell us we ought not to know;

Shouldn't we, indeed? Why so.

Fast young ladies?

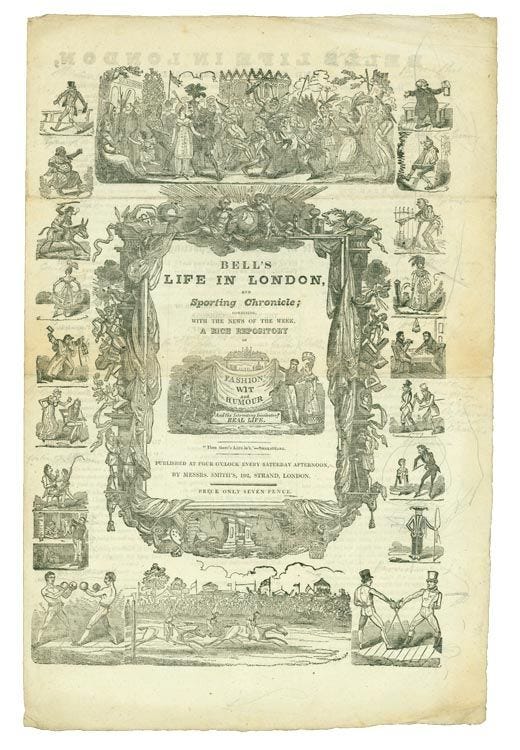

On the Turf we show our face.

Fast young ladies;

Know the odds of every race,

Fast young ladies;

Talk, as sharp as any knife.

Betting slang — we read Bell's Life:

That's the ticket for a wife,

Fast young ladies!

We are not to be hooked in.

Fast young ladies;

I require a chap with tin,

Fast young ladies.

Love is humbug; cash the chief

Article in my belief:

All poor matches come to grief,

Fast young ladies.

Not to marry is my plan.

Fast young ladies,

Any but a wealthy man.

Fast young ladies.

Bother that romance and stuff!

She who likes it is a muff;

We are better up to snuff,

Fast young ladies.

Give me but my quiet weed,

Fast young ladies.

Bitter ale and ample feed,

Fast young ladies;

Pay my bills, porte-monnaie store.

Wardrobe stock — I ask no more.

Sentiment we vote a bore,

Fast young ladies.

But on the whole, slang was a no-no for girls. Or what passed for examples of the lexis. On 16 January 1860, writing of ‘American Slang for Ladies’ the Melbourne Age recalled:

I remember once being in company with a belle — one who had had a winter’s reign in Washington. Some kind of game was in progress, when in a moment of surprise, she exclamed ‘My gracious!’ [...] I tell you that woman fell as flatly in my estimation as if she had uttered an oath. A lady, fresh from Paris, once informed me that it would do the residents of a certain village a great deal of good to be ‘stirred up with a long pole.’ Let us see how you like this kind of talk: — If you wish to be an ‘A No. 1’ woman; you have got to ‘toe the mark,’ and be less ‘hifalutin.’ ‘You may bet your head on that.’ You may [...] ‘spin street yarn’ at the rate of ‘ ten knots an hour you may ‘talk like a book;’ you may dance as if you were on a regular ‘break down,’ you may ‘turn up your nose at common folks,’ and play the piano ‘mighty fine’ but I tell you, ‘you can’t come to tea.’ You may be handsome, but ‘you can’t come in.’

You might just as well ‘cave in,’ first as last, and ‘absquatulate,’ for ‘ you can’t put it through,’ ‘any way you can fix it.’ If you imagine that you may ‘ go it while you’re young, for when you’re old you can’t,’ ‘you won’t come it by a long chalk.’ ‘ Own up’ now, and ‘ do the straight thing,’ and I’ll ‘set you down’ as ‘ one of the women we read of.’ If you cannot ‘ come up to the scratch,’ why I must ‘ let you slide.’ But if you have a ‘ sneaking notion’ for being a ‘ regular brick,’ there is no other way — ‘not as you knows on.’ If a young man should ‘ kind o’ shine up to you,’ and you should ‘cotton to him,’ and he should hear you say ‘ by the jumping Moses,’ or ‘ by the living jing,’ or ‘ my goodness,’ or ‘go it Betsy, I’ll hold your bonnet ‘ — ‘you bet!’

This is an odd list and there were few that really reflected the potential of the mid-century slang vocabulary. At least half the ‘American Slang’ is image rather than actual slang. Sometimes the commentator – again in Melbourne Punch, near-obsessed by the idea of slangy girls – managed something better. In its series, ‘Women of the Time’ the paper offered ‘The Melbourne Barmaid’ and nicknamed her ‘Miss Slang’.

On your approach, [she] offers you her hand in the approved (so far as I am concerned, disapproved) manner of the class [...] the fair paw is not always clean; it is, alas! too often clammy, through frequent recourse to damp glass-cloths; sometimes it is sticky, owing to the viscid quality of some of the beverages, and this is a ‘cordial’ description of hand-shaking that I cordially hate. [...] After the invocation of manipulation, she inquires whether you prefer a ‘nip’ to a ‘long drink;’ shall it be ‘malt’ or ‘soda and a dash?’ Do I go in for Prunier or stick to battle-axe? She knows all the sporting youths of the town— those flashy boys who affect brass horse-shoe scarf-pins, the coat of the species, and the tight-legged trouser, the last worn to indicate that they are, or would be, legs. She talks to these precious youths in their own language, discourses of horses likely to be ‘'scratched,’ and can tell the chances of each for the ‘cup.’ She alludes to meals as a ‘feed,’ and I think I once heard her speak of a dinner as a ‘blow-out,’ and a supper as a ‘tightener.’

In truth the fast young lady’s slang is pretty vapid. Certainly the mildest end of the lexical spectrum. The Illustrated Police News of 1 June 1889 noted ‘awful’ ‘lawfully,’ ‘nice,’ ‘pretty,’ ‘lovely,’ and ‘jolly’ (‘Lillian’ - the News’ generic FYL - prefers ‘jol’ and also uses ‘floored’, ‘old fogy’, ‘cram’ [and] comments that, ‘Altogether, they are such a game!’) The News categorizes them as ‘young lady slang words’ and rejects the lot since, however well they work in standard English, once slanged they ‘suffer from the defect of being absolutely meaningless.’ The Times added its male condescension to ‘the feminine adverb “awfully”,’ the Pall Mall Gazette damned female slangsters with the faintest of praise and the Sydney Morning Herald, with galumphing, condescending humour, paraphrased the lot:

‘Awfully is a schoolgirl's idiom […] It is a hen word, the hen of our fathers’ more robust expletive ‘deuced’ or ‘devilish,’ just as ‘fib’ is the hen of ‘lie,’ and ‘poorly’ is the hen of ‘seedy.’ A ‘hen word’ is good...but a schoolgirl idiom must surely be a pullet word.

The real masculine of ‘awfully’ is a six-lettered participle, which the Pall Mall no more dare print unasterisked than it dare call a spade a spade in this spadonic age.[13] Expletives of this sort, whether strong or weak, of course prove poverty of imagination and unreadiness of speech [...] And for the ladies, who must devote so much time to flirtation, and to decoration of themselves […] we think much allowance should he made. Let them have their ‘little language,’ their slang in petticoats. Shall we make it classical by publishing a lexicon of it?

In 1879 the Burlington Free Press (VT) kept up the attack. ‘The poorest, feeblest and most vicious slang [...] is the fashionable slang which pollutes the lips of young girls. ‘Awfully jolly,’ ‘Immense,’ ‘Ain’t he a tumbler?’ ‘He has a great deal of the dog on to-day,’ ‘Good form,’ ‘Awfully first-rate’ [...] ‘Didn’t we have a stationary fling though?’ meaning [...] a stupid evening ‘Quite too awfully handsome,’ ‘Pitch on your hat, and let’s go for a picturesque’[14] It was all getting very rote.

The moral panic, like all such eruptions, burnt high and hard but soon guttered out. If for no other reason than from contemporary reports, its target seems to have been a class-ridden creation. Her slangy, cigarette smoking, huntin’, shootin’ and ridin’ persona could never embrace the great unwashed. Not only that, there was an even more immediate failing that must, it was promised with undisguised relief, bring about her decline: male disapproval.

In March 1868 London’s Saturday Review forecast her decline, and hoped for the resurgence of her sister ‘the simple and genuine girl of the past, with her tender little ways and pretty bashful modesty.’ The bottom line, suggested the Review, was that men, whatever these new-fangled girls might believe, were unimpressed. ‘She thinks she is piquante and exciting ...and will not see that though men laugh with her they do not respect her, though they flirt with her they do not marry her ; she will not believe that she is not the kind of thing they want, and that she is acting against nature and her own interests when she disregards their advice and offends their taste.’ It might not happen at once, acknowledged the writer, but there was time a-plenty and ‘all we can do is to wait patiently until the national madness has passed, and our women have come back again to the old English ideal, once the most beautiful, the most modest, the most essentially womanly in the world.’

She did, at least in this incarnation, fade away, but she would be back, and far more threatening to an established order. Let us leave her with this piece in the Leeds Times of June 1895:

THE ALPHABET OF SLANG. A prize offered by the ‘Gentlewoman’ for the best ‘Society slang alphabet’ has been won by Miss Moutray-Kead, a Herefordshire lady, with the following :

It's ‘awfully’ difficult everyone knows.

A ‘bally’ slang alphabet thus to compose ;

I feel more like ‘chucking’ the whole blessed show,

Being ‘dotty’ and ‘done’ at the very first go.

It's ‘evens’ my getting as ‘edgy’ as you

Will become if you do not ‘funk’ reading it through.

‘Get out! Hook it! Hang it all!’

This is ‘intense;’ If I ‘jack’ it up now that would be ‘jolly’ dense,

Why, even a ‘kid’ would scarce ‘kick the bucket!’

So why, for a ‘lark,’ should this ‘lunatic! chuck it!’

I'd wager a ‘monkey,’ if I had the ‘needful’

But the ‘oof-bird’ is moulting, so needs must be heedful

That some other ‘pals’ are now having a shy

For a Q. Will they find one? ‘Query,’ say I

What ‘rot’! This is ‘riling’; but most so to me.

Don’t get ‘shirty,’ or lose your wool over a ‘spree.’

Excuse this bad language, and just take my ‘tip,’

Don’t try for slang prizes betwixt cup and lip, Etcetera

To go to their ‘uncle’ would anyone choose

(I’m hard up, as you doubtless already ‘vermoose’).

The ‘wherewithal, X,’ minus quantity, ’s wanting,

Preventing the buying from P. R. or Ponting,

Where ‘yellow boys’ only they’ll take, they’re such ‘zanies.’ [15]

[1] for whatever reason, while the text rhymes, it was laid out as continuous prose

[2] the mobile and static versions of fast are both based on Gothic fastan, to keep guard; the first suggesting the vigorousness that underpins the act of guarding, the second its immobility

[3] ‘A London Antiquary’ A Dictionary of Modern Slang, Cant and Vulgar Words (1859)

[4] Saturday Review (London) 28 July 1860

[5] T. Taylor A Lesson for Life (1867)

[6] Melbourne Punch 20 Nov. p. 7/1

[7] Melbourne Punch 12 Dec. 1861

[8] Melbourne Punch 5 Feb. 1863

[9] M. Schele de Vere Americanisms (1872) p. 574

[10] Wallaroo Times and Mining Journal (Port Wallaroo, SA) 16 Nov. 1867

[11] Melbourne Age 7 Mar. 1868; the Bal or Jardin Mabille (1831-75) was an open-air dance-hall in Paris, known for its population of prostitutes, and birthplace of the polka and the can-can

[12] Inquirer (Perth, WA) 28 Nov. 1860

[13] presumably bloody, aka ‘The Great Australian adjective’

[14] Burlington Free Press (VT) 1 Aug. p. 4/2

[15] Leeds Times 16 June 1895

Well. Thanks for the infuriating reminder of how women have historically been relegated to the bottom of societal respect for daring to be humans, to live in equality, for wanting joy, comfort, and freedom that men take, not as privilege, but as a given. And because we are constantly denigrated for wanting the same human rights as men, and are losing our rights apace, let me just say Fuck This.

Thank for another great essay.