I am 76 and change. A number of little import save that male life expectancy for those born in England is currently around 80 and thus my days, without requiring the slightest mathematical expertise, may be numbered. Given the state of the country I left three months ago, I cannot pretend to much regret at my brevity, even if there are certain individuals whose death – accident, illness, I care not, but sustained and savage torture, the punishment properly fitting the crimes, would be most condign – I would delight in knowing were notched up before my own*. But even were that so, it has no bearing on the fate of the project to which I have devoted all but ten of my adult years: the seeking out, collection, elaboration of linguistic roots and setting out of (ideally) accurate definitions and senses and ultimately the sorting in alphabetical order of the terms that I glorify as the ‘counter-language’ and my fellow lexicographers and the wider world prefer to nominate as ‘slang’. The first of my hard-copy dictionaries appeared in 1984, the most recent in 2010, and this, after transmuting into an online digital version in 2016, enjoys a revision every 90 days.

I am 76 and change. I cannot continue for ever. But it is my wish that my lexicon should. OK, not forever, a dangerous promise, but I would certainly prefer that the ‘book’ should not vanish alongside its creator. GDoS offers 738 synonyms for ‘death’, ‘dead’ and ‘die’ and I see no reason to stop things there. Up till now continuation has been simple: I want another dictionary? that the last edition is now out of date and should now merely prefigure its replacement? then sit down at the screen for yet another day or many more, and make one. But without a sitter? Here comes the problem.

The Internet cut down some of the tallest poppies in reference publishing and I am the first to admit, for a big dictionary digital is the golden road. Both lexicographers and users have benefited enormously. The removal of space restrictions, which had played so dominating a role for the print OED, would be a triumph in itself. Add in the sophistication offered by digital search (not to mention its speed), the possibility of far more frequent updates…not to mention the economics: no more outlay on all those pages, all that print. GDoS has also benefited and I tip my hat every day.

Off the top of my head the only major dictionary (multi-volume, working on ‘historical principles’, which means usage examples or citations) that one might term ‘future proofed’ is Oxford’s OED. (Smaller ones, aimed at school/college presumably are more likely to appear, even in print). And we know from its histories, whether that of Katharine Murray or more recently Peter Gilliver, the extent to which every day of its existence has been a struggle against those who are allegedly its supporters and financiers. Bean-counters will count, whether Master of Balliol or otherwise. Publishers, however grand, are ‘trade’ and trade seeks, depends on profit. They may not tell you so as the flattery dances across that initiatory lunch table but thus it is. And if ‘they’ must be dragged like a genuinely unwilling Speaker when it comes to the national treasure that is the OED, am I really to expect a rush to support the unveiling of yet another synonym for gherkin-jerking?

So we have, thank goodness, Oxford. Is it the last lexicon standing? Is there, say, a US equivalent any longer? I don’t believe so (though I am wholly willing to suffer knowledgeable corrections on all my assumptions). Webster’s Third appeared in 1961 (amongst much controversy -who’d have thought the word ‘ain’t’ would be so terrifying?) and that mighty tome never arrived at a fourth edition though of course Merriam-Webster remains a power in the land. French? The Trésor de la Langue Française began publishing its 16 volumes in 1971, but shut up shop on ‘completion’ in 1994, leaving only an online facsimile with no intention of revision. Le Grand Robert is the go-to dictionnaire now, but while it offers some cites, it does not embrace full ‘historical principles’. German? Well, the great Deutsches Wörterbuch, pioneered by the Grimm brothers in 1838 and ‘finished’ (32 volumes) in 1961 is working on an update but we had better not hold our breath. Down Under? Better news: the Australian National Dictionary (with multiple citations) published a second edition in 2016 and the rival Macquarie reached its tenth, ever expanding edition in 2023 (again, sans citations).

So my sense is that while a few of the reference publishers have survived the Internet and successfully recreated themselves, the great ‘Victorian’ works of exploration, tied in their various ways to bigging up the nation of publication, are a thing of the past. Too big, too chronologically demanding. Too costly. Back we come to the OED. And is little GDoS, which may have sold 1800 sets of its three hardback volumes, but never really made penny one as a website, and has not had a supportive publisher since 2009, to challenge that new lexicographical order? I would set it alongside the 'Victorians' in its (author's) insatiable omnivorousness and its aim for completeness (or at least 'keeping up'), but get real... Yet I believe it to be of value in what it permits users (scholarly, civilian, journalistic, serendipitous...) to do and would like to preserve that value. I don't see it quoted as a source of authority as often as I do without feeling it is of worth. At the moment I can satisfy my side of the bargain by keeping working and as I have always said, I intend to draw my last breath crashing forward into the keyboard.

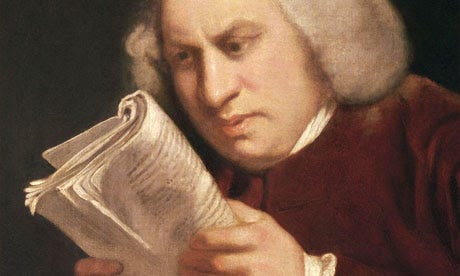

But as Johnson noted of the breadth of his hopes for his own dictionary: ‘...these were the dreams of a poet doomed at last to wake a lexicographer'. Of course he failed, we all do, but he failed better than most. But SJ, had he glanced down mid-19th century from his posthumous drinking and arguing with Captain Grose and his other, grander acquaintances, would have been able to see, here was this cleric, Chenevix-Trench, proposing a successor, and this madman who multi-tasked editing academic journals with conducting a teashop girls' rowing eight, Furnivall, taking on the job and this Lowlands teacher, Murray getting it done. I cannot claim such hopes. I am not, I trust, so arrogant. My work has long since become co-terminous with my life but that is no-one’s problem beyond mine. It is not the ‘Green’s’ that matters, but the ‘Dictionary of Slang’.

Nonetheless, while I shall have left the building, we must assume that there will remain a future. And if the building stands, though I will be scattered elsewhere, I would like GDoS to find its corner, minuscule though it must be.

Though what I (and those others to whom I am so grateful) have made, let me ’fess up, is no mighty edifice; the words string and gaffer-tape spring lipwards. It was always so. It exists ‘despite’ as well as ‘thanks to’. The great John Mitchinson, then boss of Cassell, where I had produced two editions of the Cassell Dictionary of Slang (no cites, too much Eric Partridge), commissioned the big one. But was it two or three years later when Cassell was gobbled up and John moved on. The new owners, somewhat higher up the Pacman scale wherein saurian publishers munched on each other’s still-warm vitals, informed me that the contract would hold and that they would publish, ‘if we have to’. I started looking for an alternative backer.

Nearly, oh so nearly – when they said ‘yes’ I cried with relief – but even as we danced altar-wards, the pre-nup reared up and frankly my dear, I did give a damn. No fucking way was I signing that. No tears, other than those of rage, this time. Then a proper offer. I took it. We published a single-volume subset of the on-going GDoS together. But was it even two years before they too went tits-up. An even vaster monster pronounced, reluctant as ever (fair enough, they had already eaten two of my lesser friends, and, preferring juicer morsels, spat me out), that they would abide by some of the contract (no digital version, and if I complained…then no version full stop.) The print version appeared in 2010. I shall whinge no further. The digital, thanks to a remarkable piece of unexpected happenstance, in 2016. I revise every three months. I shall die at work, if it does not kill me first.

Which brings us back: I shall die but GDoS may perhaps live. I have been talking to my co-conspirators and supporters Jesse Sheidlower and James Lambert. Jesse, formerly of the OED in New York, has been a friend of my dictionary for maybe 20 years. James, late of Macquarie in Australia, is my contributing editor and his contribution is mighty. They are younger than me, they are keen to make things continue. But I say again: string and gaffer tape. During pre-print the years of research I used a couple of piece of database-cum-editing software (they changed when Cassell went under). The owner of the second of these, Philippe Climent of IDM (who also services the OED and other reference publishers) was kind enough to offer me free access to the software once I had no publisher to pay the bills. For ‘kind’ please read whatever superlatives you prefer. No software, no GDoS. It really is that simple.

Thanks to a legacy, itself properly Victorian in its unexpectedness and its munificence, I have been able to assume that desirable but on the whole vanished role: the ‘gentleman scholar’** (I suggest the word ‘independent’ is more my style. There is much solitude, but I have no problems with that. Scholar? Eyes of the beholder, I guess.) In other words working very hard without an actual income. This has proved useful: no-one, as I have noted, has offered me one. Between 2010 and 2014, when my digital saviour emerged via what was then a Twitter that still worked for good rather than its antithesis, I searched for a patron. Publishers simply barred their door. Academic institutions pleaded either lack of funds or of digital skills. Businesses asked ‘what’s in it for us’ and at my answer ‘the pleasure of supporting something of value’ only managed to halt their laughter when they realised they must summon an underling to escort the loony from their premises.

Why should any of that change? That’s the question now. Like ‘retire’ the word ‘monetize’ remains a stranger to my database. (If there are two stereotypes of my race – the pedlar and the Talmudic scholar – I am a half-assed version of the latter.) I can, on the other hand, write letters and I shall. Back in 2010 I essentially arranged my own publicity and begged acquaintances for reviews. I can unlock that box again. My co-conspirators will undoubtedly have their own suggestions. It is a decade since I last searched and much has changed. Let us see.

Meanwhile, work beckons. Time for another look at Sydney Baker’s list of ‘Australian Vulgarisms’. How’s about a quick sandscratch? Now that’s my comfort zone.

_________________________

*Yes, this is utterly appalling and I am perfectly well aware of it, but I am fortunate in having side-stepped that belief system which adjures its adherents to turn their other cheek, opting instead for that which takes eye for eye and indeed flays the smirk and smugness from the lips.

**The definition of ‘gentleman’, to me, is one who would never hit his wife without previously removing his hat. I have believed for decades that this was a Raymond Chandler coinage, but it seems otherwise. I begin to wonder if I made it up myself.

Benjamin, You are truly far kinder than I deserve. But GDoS, yup, I'll accept all bouquets on the old thing's behalf. Not to mention everyone who in one way or another has made it happen. And now I have to keep breathing: online hits a decade in 2016.

I stand, somewhat shakily, amidst the ruins of publishers who went before.