[Perhaps it’s these inescapably grim times, and really, how are we supposed usefully to flee, prostrate in Putin’s pit and awaiting Trump’s pendulum; maybe it’s the imminence of farewell (and the admission that hanging about is decreasingly worth the effort); maybe it’s just a recognition of the ever-widening abyss between the collector and the creators and users of the latest examples of what he has been collecting for multiple decades…whatever the excuse, I’m going ever-further back. Back that is, in slang research. Blessed by access to Early English Books Online (EEBO), some 146,000 texts from the late 15th century to c.1700, I am looking at the 7000-plus GDoS headwords (2,500 from 1500-1599, the rest thereafter; expansion being slang’s leitmotif as every year passes) that fit the bill and seeing, as it were, if with EEBO’s aid, I can move some of them a little higher on the roster. Most often I am finding interdates that plump up what I have already offered, but when the gods of lex are even kinder, I can push first recorded uses further back. As ever, such is the grail.]

‘He had strayed from conventional language into rough, truthful speech’.

Anthony Trolloppe The Eustace Diamonds (1871)

For those who would have answer to the perennial question, what is slang, there exist a variety of answers, both academic and popular.

Whether, as one observer suggested, it is the working man of language, doing the lexicon’s ‘dirty work’, the language that as the grindingly populist poet Carl Sandburg put it, ‘rolls up its sleeves and goes to work’, or, as John Moore offers in You English Words (1962), it is ‘the poor man’s poetry’ (refined in 2009 by the American academic Michael Adams as ‘The People’s Poetry’) standing up for the disenfranchised, or, as its many critics still proclaim, it has nothing but the most deleterious effects on ‘proper speech’, slang remains a law unto itself.

As a linguistic phenomenon it surely predates Christ1. The mid-nineteenth-century slang lexicographer John Camden Hotten, as keen as any other Victorian scholar to find antecedents in the classical and pre-classical worlds, offers the readers of his Slang Dictionary (1859) an alluring, if somewhat fantastical picture of this ‘universal and ancient’ species of language. ‘If we are to believe implicitly the saying of the wise man, that “there is nothing new under the sun” the “fast” men of buried Nineveh, with their knotty and door-matty looking beards, may have cracked Slang jokes on the steps of Sennacherib’s palace; and the stones of Ancient Egypt, and the bricks of venerable and used up Babylon, may, for aught we know, be covered with slang hieroglyphics unknown to modern antiquarians...’. And the Phoenicians, the Greeks and the Romans all, presumes Hotten, had their own slangy speech.

Greeks, Romans, yes.2 The rest, who knows. We must stick to proof (though proof, as one finds in pursuit of language, is always up for re-analysis). As a word in itself slang does not appear in the (printed) language before the mid-18th century. As things stand, it is generally agreed that the word’s first use as a reference to criminal language comes in William Toldervy’s four-volume novel The History of Two Orphans (1756): ‘Thomas Throw had been upon the town, knew the slang well.’ However the slang in question is somewhat vague: was it non-standard language pure and simple or was it more metaphorical, a style of dress and/or manner that set young Mr Throw among the fast-living men-about-town? Was he even a criminal? The line continues ‘…and understood every word in the scoundrel’s dictionary.’ But knowledge does not guarantee enlistment.3 There is an earlier instance - ‘My lord Slang is one of the merriest men you ever knew in your life; he has been telling me a parcel of such stories!’ in Henry Fielding’s comedy Don Quixote in England (1734) but again, whether milord is a raffish raconteur, or a gentleman’s master as well as a mere gent, is impossible to tell. And sadly, he remains off-stage.

Certainly by the turn of the century, when such young men were known as The Fancy (a term first used of pigeon fanciers but elevated to the prize-ring and the turf), a knowledge of slang was a prerequisite of the type. Pierce Egan’s bestseller, Life in London (1821), which first brought us that long-lived team ‘Tom and Jerry’, owed much of its success to its use of such terminology. And by the mid-19th century ‘slang’ had also begun to be used as an alternative to jargon (itself most simply definable as ‘professional or occupational slang’) and such luminaries as Charles Kingsley (in a letter of 1857) and George Eliot (in Middlemarch, 1872) referred quite naturally to the ‘slang’ of, respectively, artists and poets. In 1853 Dickens, through his mouthpiece George Augustus Sala, excoriated slang in Household Words, but his villain seemed to be verbal affectation, no matter what its source; the lists of ‘real’ slang are much too impressively knowledgable to suggest a genuine disdain.4 Meanwhile the modern meaning of the word, if not its vocabulary, had been enlisted in Standard English by the mid-century and dignified by John Keble (in 1818), Thackeray (in Vanity Fair [1848]) and many other respectable users. In 1858 Trolloppe, in Dr. Thorne, speaks of ‘fast, slang men, who were fast and slang and nothing else’, a citation that points up both their language and their rakehell, buckish style. But Trolloppe, as noted in my epigraph, also appreciated that slang, in more general terms, was ‘rough, truthful speech.’ Enough, as they are supposed to say, with the definitions.

Ultimately slang seems to be what you think it is. An empty vessel into which any and everyone can pour the filling of choice. Fittingly, it parallels that other notorious defier of simplicity, obscenity, which, as a number of judges have declared, is something we know when we see it.

In the end, I’m with that old reprobate John Camden Hotten whose day-jobs moved between plagiarism and pornography. His Slang Dictionary appeared in 1859 and ran to five editions before its author died in 1873. It remained the best example of its kind for the next twenty years and it’s author’s comments remain pertinent.

‘[S]lang represents that evanescent, vulgar language, ever changing with fashion and taste,...spoken by persons in every grade of life, rich and poor, honest and dishonest...Slang is indulged in from a desire to appear familiar with life, gaiety, town-humour and with the transient nick names and street jokes of the day....slang is the language of street humour, of fast, high and low life...Slang is as old as speech and the congregating together of people in cities. It is the result of crowding, and excitement, and artificial life.’

So we have this slang, this counter-language, this lexis of synonymity, this ever-expanding temple of subversion. It must come from somewhere. People demand that such should be the case. It has creation myths. Like the Biblical original they are undoubtedly unsound. For criminals, they involve a great leader and his community of larcenous beggars and the establishment of codes both social and linguistic. In France it was le Grand Coesre, a word surely linked to Caesar, who, clad in a coat of interlinked coins, gathers his followers and lays down the laws, including those of secret communication. In England it was one Cock Lorel, King of the Beggars, who performed the same office, bringing his people together at the pleasingly named Devil’s Arse Peak in Derbyshire. But since cock lorel means no more than what modernity terms a ‘top villain’, then, or so I hope, slang’s creator was his successor, another pleasing name: Jenkins Cowdiddle.5 What we do ‘know’ is one Cock Lorel invited the Devil to dinner.6

But if as I believe slang is hard-wired - if linguistically we have a yay (standard) then its nay (slang) follows as night does day - then creation myths are just that: myths. The French term argot denoted a people before it was a language (or rather jargon) and when it became a language, then it was for criminals only. In France, at least, this was probably true until the last world war: the milieu had its own lexis (la langue verte, the green tongue: perhaps from the green baize that covered gaming tables or from the ‘green’, i.e. raw crudity of its lexis) and it, as much as any street, delineated its boundaries. It was not the same as l’argot commun, the slang of civilian life.

To keep it anglophone there is argot’s equivalent, cant, the language of full-time crims (and attributed at first to scofflaw mendicants), which comes from the sing-song chanting (Latin cantare, to sing) of prayers as offered by slapdash priests and their bored congregations. It is harder to see where cant and the slang of the common user draw their lines. On which side is Henry Lemoine’s poem ‘Education’ (1791): ‘A very knowing rig in ev’ry gang, / Dick Hellfinch was the pink of all the slang’, with its use of the term for people not speech.

Cant-specific dictionaries abounded, albeit plagiarizing relentlessly each from its predecessor, until the 19th century. But by the end of the 17th they were already being overlapped and the cant words that appear in volume after volume are estranged ever further from their original users.

My long-held belief, the stimulus for this post, is that despite the lack of records, there was a non-standard language long before 1756. That it was spoken by London’s non-criminal working class and that it forms the foundations of my own work.

If one does a count, then by the time Thomas Throw and his creator are credited with associating the word with such language, then, at least as recorded in GDoS, there are 9,297 earlier terms that are accepted (at least by me) as part of the slang canon. Which makes around 11% of the current 83,500+ headword lexis (though the maths gets slippery, given that no two databases offer the same answer.)7

I have been trudging through EEBO, trying to keep focused, trying not to linger on some particularly choice text (I own to an irresistable evisceration of Richard Brathwaite’s Ar’t Asleepe, Husband (1640)8) since early November. I have reached (one’s) fingers are made of lime-twigs, used (by ‘civilians’) to denote a thief, whose fingers, like the tree’s sproutings, are ‘sticky’. Its first use GDoS is 1596 and I hope that if EEBO has noticed it, then it will be sometime earlier. So far I have touched on 369 terms. In most cases I am seeing infill, covering often substantial gaps in the record, but there is a steady flow of predates. It is (nearly) always older than you think.

The initial recording of non-standard English (and presumably French, Italian, German, Spanish and others) was patchy. All the countries I mention focused on the languages used by their criminal classes. There seems to have been little attempt to look at the language of the law-abiding working-class. Decades prior to the first English-English (i.e. not English-Latin, English-French etc.) dictionary (Cawdrey’s Table Alphabeticall of 1604) the 16th century saw a number of specialist collections, be they of husbandry, archery or, with no difference other than the words and no doubt the sales, criminal jargon. But if there was a vocabulary coming out of the city, which in England meant London, it found no lexicographical home. There must have been a working class, servants of course, but in, for instance, the manufacturing and food-and-drink providing trades too. The prototype of Thackeray’s Jeames might have aped the masters and mistresses whose farts he caught, but the porters of Smithfield, the bummarees of Billingsgate, the landlords and ladies and the staffs of inumerable inns and taverns did not. They did not, surely, speak the language of the nobs. But the embryonic lexicographers either didn’t care or didn’t know. Printing was still new and promoted elitist texts, often religious. The masses, anyway, often didn’t read. But crime sold, as ever it would, and it dervived authenticity, as it still does, from embroidering criminality with the words it created and used.

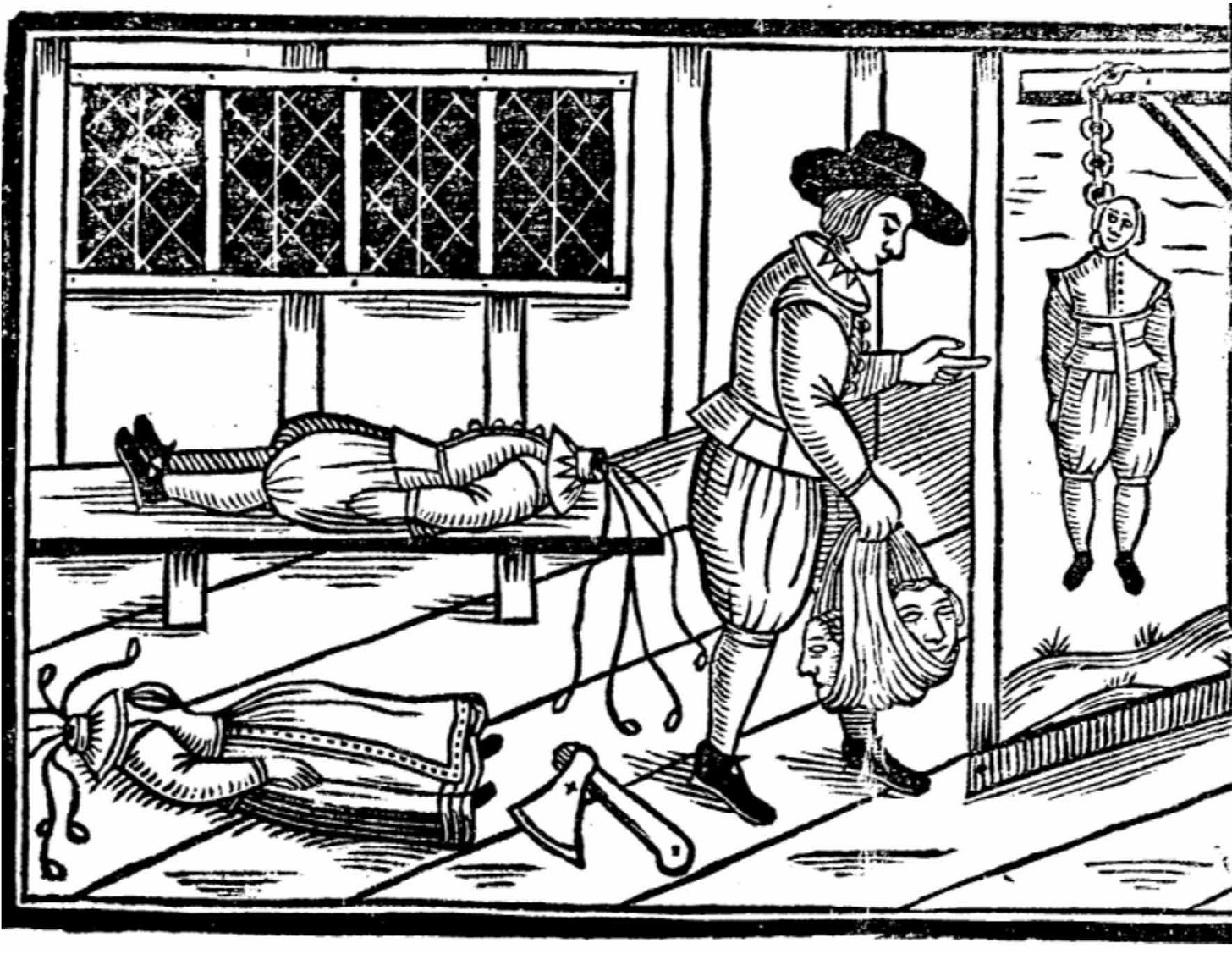

Because cant sold, we know where to find it: a succession of short books that appeared in the mid and late 16th century. France had started fifty years earlier, other states followed suit, but the style, known as the ‘beggar book’ was pretty much the same. You laid out the main villains, named them, explained their speciality and perhaps threw in some allegedly ‘real-life’ anecdotes. To round it off there would be a vocabulary, for the punters to ‘take home’ with them, as it were. Maybe illustrated by some stilted, but cant-filled ‘conversations’.

None of which was extended to city’s cits or cockneys. Let alone its Master and Dame Average. Yet reading through EEBO, checking off and ideally improving on the early material that research has piled up, one can see that there was another non-standard language, even if this version lacked the melodramatics of cant. When the time come, and like its standard peers, it would move not into mainstram lexica, but in 1698 into the slang lists of the otherwise anonymous B.E. Gent and, a century on, the highly visible Francis Grose.

My excursion into EEBO helps, but it is limited. The beggar books are here with the arcana of their vocabulary, plus authors such as Thomas Dekker and Robert Greene who followed and exploited them and published their own canting pamphlets. There is also a good deal of language that, while not cant, will find itself already listed in my database. It is that which I am pursuing and checking. It is likely that in many cases such language was not classified as ‘non-standard’ as yet. But the sense is of words and phrases that in time and for whatever reason, didn’t make the cut. Like the obscenities which were once used quite casually - simple bodily parts and functions, why make a fuss? - they were set adrift, to be rescued by my welcoming predecessors.

So onward to flesh-hooks, flirt-gill, furze-bush and beyond. Take up thy quill, Mr Slang, and labour. Scholar or otherwise, that lurking skull won’t wait for ever.

Christ himself, or rather those who sermonise in his name and are recorded in EEBO, use a surprising amount of it, at least of words that will make their way to GDoS.

I offer as an example Prof. J.N. Adams The Latin Sexual Vocabulary (1990). Different words, the same old imagery: the penis as a weapon, the vagina both desirable and terrifying. Imagination has always had its limits and slang, bowing to archetypes, is a good Jungian.

As for on the town, GDoS does not really help. All senses specify lifestyle: 1 (1727+) is prostitution, 2 (1756+) professional criminality, 3. (1819+) social sophistication. But my dating of 2 is based on Toldervy and do we really know?

I refuse to accept Dickens as anti-slang. Of all his contemporaries he is, in this as in so many other ways, the most sophisticated user of the lexis. He may have consulted a slang dictionary, but you do not see the joins. He is cited 624 times in GDoS.

Whether or not Jenkins’ surname had been earned via quite literal fieldwork has been long unanswerable; diddle - https://greensdictofslang.com/entry/fdmiapi - certainly existed in the required sense.) It may, now I ponder further, have been simple stereotyping of the rural Welsh.

The proceedings - featuring the consumption of, inter alia, various authorities, a nun and a priest, a lecher and a cuckold, a usurer and ‘a harlot’s head with garlick’ - are recounted in the broadsheet ballad A Strange banquet, or, The Devils entertainment by Cook Laurel at the Peak in Devonshire with a true relation of the severall dishes printed sometime between 1678-1680 (you can read it here, albeit in black-letter.)

For instance my research database, the one into which I put the raw data and tag it up for XML recognition, tells me I have 57,335 headwords which in turn hold 144,415 senses. GDoS, the digitized, online transmutation of that research into mass accessibility, comes up with 83,414 entries, holding 127,101 senses. I have no idea of the underlying count mechanisms that give such widely variant answers. I cannot even play lexicography’s game: size does matter, because there is no consistency in that either. Back to work.

The full title: Ar’t asleepe Husband? A BOULSTER LECTURE; stored with all variety of witty jeasts, merry tales, and other pleasant passages; extracted, from the choicest flowers of philosophy, poesy, antient and moderne history.

More usually a curtain lecture or sermon, as in those that surrounded a four-poster bed, the term, featuring the (likely justifiably) nagging/scolding wife and a husband who is trying, at least pretending to sleep, flourished from the early 17th century to the early 20th. My last example is from ‘the Jane Austen of the 20th Century’ (J. B. Priestley) who noted in her novel The Priory (1939) ‘Curtain lectures are often the only ones a woman is allowed to give.’ (more illustrations here: https://sarahalbeebooks.com/behind-the-curtain/)

You write beautiful prose, fully worthy of its subject