Slang is urban and so am I and horses have never entered the picture. Maybe it’s some residual memory of Cossacks. At the Lincolnshire Handicap of 1953, I was seized and brandished aloft by the tipster Ras Prince Monolulu who was neither the Abyssinian prince that he claimed, nor remotely of that name but actually Peter Mackay from the Virgin Islands. He may have blessed me with his trademark cry of ‘I gotta horse’ but that I cannot recall and while what I do remember is a top-hat, all pictures seem to feature some kind of head-dress. Three years on, visiting the Nottingham Goose Fair, my well-meaning parents, seeking no doubt to entertain me, placed me atop what was doubtless the gentlest of nags. It moved. I demanded instant rescue. (A contemporary invitation onto the footplate of the record-breaking loco Mallard produced similar results. Cowardy-effin’-custard!). In 1978 I compounded the aversion by failing to punt on that year’s outsider winner of the Grand National, its name almost that of my still very infant first-born. That was it for horseflesh.

But times would change.

Around 2010, I met Robert Smith Surtees. I had heard of him – usually via a variety of slang investigations – but had failed to bite. Kipling’s schoolboys Stalky & Co. read him religiously but they were not, to that extent, role models. I should have read further, or perhaps taken more punctilious notes. In Kipling’s short story ‘My Son’s Wife’ (1917) I would have found slang’s dream of perfect heaven.

The earnest young aesthete Frankwell Midmore is reading at random in the library of the country estate he has inherited and, wholly reluctantly, is visiting. The volume he has plucked down is Surtees’ Handley Cross, a sequel to his debut venture Jorrocks and one of his best-known, if not as magnificently, roguishly harum-scarum as some later titles. It was sufficient: in Kipling’s words, ‘It was a foul world into which he peeped for the first time, a heavy-eating, hard-drinking hell of horse-copers, swindlers, match-making mothers, economically dependent virgins selling themselves blushingly for cash and lands, Jews, tradesmen and an ill-considered spawn of Dickens and horsedung characters.’ To his credit his horror (though in terms of the delights of degeneracy the book is pretty restrained) turns to fascination with the author, who the modern publisher Jeremy Lewis, noting his ‘sceptical, brisk, tough-minded and unsentimental’ style [and] his ‘rumbustious, agreeably coarse-grained prose,’ termed ‘the hard man of the English novel’. Faced with a true page-turner, he takes the text to bed.

I had read foxhunting novels – George Whyte Melville and his coevals – but stuck to the slang chapters, usually occasioned by papa’s importunate descent into the hands of the Jews and the necessity for the young heir to masquerade as a stableboy, with language to suit, prior to winning the Derby and, his toff status reassumed, the conveniently wealthy heroine’s hand. Like many erstwhile Victorian best-sellers, they are lost to modern readers and the dust mounts ever higher on spines bedecked with whips and horseshoes. But following Christopher Hitchens’ then recent and sadly premature death, I found myself rereading his mentor Orwell, and through that Orwell’s take on Dickens, and in that, his encomium of Surtees. I do not argue with Orwell.

Surtees (1805-64) came from Co. Durham gentry, had gone down to London at 20 and while stumbling through an unsatisfactory career in law started freelancing for the Sporting Magazine, a slightly more raffish version of the Gentleman’s Magazine, once home of Samuel Johnson. There he would replace its hunting correspondent ‘Nimrod’ (C.J. Apperley) even if, while a lifelong foxhunter (and an enthusiastic shooter), and in time M.F.H., he was never considered an outstanding rider. In 1831 his elder brother died and Surtees quit London and the law for squiredom at the family home, now his own, Hamsterley Hall. That year he also founded the New Sporting Magazine, after being refused a share in the original one.

He published without distinction until in 1838, using columns that he’d been writing for the NSM, came his first best-seller, Jorrocks’s Jaunts and Jollities; the hunting, shooting, racing, driving, sailing, eating, eccentric and extravagant exploits of that renowned sporting citizen, Mr. John Jorrocks of St. Botolph Lane and Great Coram Street. Mr Jorrocks, a wealthy sporting and matter-a-damn vulgar Cockney grocer, was followed by other sportsmen, both of them far less honourable men, if far more accomplished riders than their predecessor. In good Jacobean style, as would be the case with all his characters, Surtees made that clear in his christenings: stars such as Mr Soapey Sponge of Mr Sponge’s Sporting Tour (1853) and Mr Facey (i.e. cheeky) Romford in its sequel Mr Facey Romford’s Hounds (1865) or lesser reprobates as the nominatively determined Duke of Downeybird, Lord Legbail, Sir Harry and Lady Scattercash or Captains Bouncey and Seedeybuck. Not to forget the glamorous Lucy Glitters (actress and equestrienne) and the parsimonious landlady Madame Nipcheese (slang for a miser, a ship’s purser and a grocer). There were other books, both sporting, e.g. Handley Cross (1854), or social, e.g. Ask Mamma (1858) and far from every title succeeded, but the hunting was what counted. Surtees died of a heart attack in 1864. For all his popularity, no newspaper carried a notice of his death. That he had never signed his work at least suggests an excuse but in the end he was just too gamey for contemporary moralising.

Surtees’s world embodies what Orwell termed ‘the boxing, racing, cockfighting, badger-digging, poaching, rat-catching side of life’, a reality of contemporary life that Dickens almost wholly sidesteps, even if Pickwick was perhaps conceived as a potential rival to Mr Jorrocks, who at the time had yet to enter hard covers. Unsurprisingly, though here he and Dickens have something in common, his is a world that embraces slang and he offers 602 terms (Dickens has just over 730). Some of it comes from Pearce Egan, and Surtees’ characters provide a solid link between the Regency’s Tom and Jerry and the Sporting Times’ Pink Uns of the ‘Naughty Nineties’. Like Egan, but so unlike Dickens, let alone his lesser literary contemporaries, Surtees makes no pretence at imposing morality. Soapey Sponge and Facey Romford are out-and-out bounders, and their success comes from the willing, greedy gullibility of those they meet, each desperate to befriend and/or exploit the images that the pair create. Suckers every one, they receive no breaks, even or otherwise. All are against all: a properly Hobbesian state of nature for the country. Yet Surtees’ satire is not cruel, simply acute. We laugh at the humanity, necessarily exaggerated, on display.

Surtees offered an unvarnished world: his rakes were rakish and his women far from simpering caricatures. His language was suitable. As the New DNB has it, ‘His books ran counter to the currents of his age in their lack of idealism, absence of sentimentality, and almost wilful flouting of conventional moralism. His leading male characters were coarse or shady; his leading ladies dashing and far from virtuous; his outlook on society satiric to the point of cynicism.’

John Shand, writing in The Atlantic in January 1945, sums up:

‘If he has no taste for the ideal, he at least enjoys the real without bitterness. If he does not see his fellows as angels walking, he does not in disappointment call them devils. If his lovers never believe the world well lost for love, it is also true that they do not believe the world well lost for any consideration. The way of the world perfectly suits all his characters. They are completely selfish, and they view unselfishness in others with high suspicion. They adore riches and despise poverty. Altogether they imitate humanity pretty closely.’

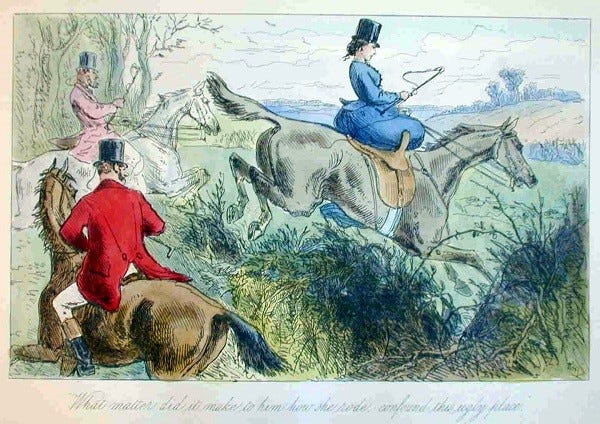

Surtees’ women, unlike those of Dickens’ usually two-tone menu of comic hags and vapouring saints, are either cold-blooded realists, if pretty, and money-grabbing matchmakers if old, or at least maternal. Not only foxes are hunted. Lucy Glitters, the London actress who marries Sponge, is described as ‘tolerably virtuous’. What’s not to love? There is sex, albeit offstage, but no religion, only hunting parsons. If there are no politics and this world cannot thus resemble Gillray it is still Rowlandson, or Cruikshank before he took the pledge. And the actual illustrator was John Leech, a Punch regular who had worked with Cruikshank, illustrated Dickens’ Christmas Carol (1843) and who with Surtees texts to help him consolidated an already substantial reputation; when he went Surtees took over Dickens’ old ally ‘Phiz’ (Hablot K. Browne). Leech’s skills also gave critical moralists an out: frustrated by the seeming popularity of so reprehensible an author, they attributed the books’ success to the illustrations.

Whether, as sometimes claimed, or not Dickens ‘borrowed’ the idea of Pickwick (serial 1836-7, book in 1837) from Jorrocks (serialized 1831-4 though not in book form until 1838), Surtees cannot step into Dickens’ light as regards literary quality, but he can do description as well as the master. Better? His hunts, unsurprisingly, are outstanding and even this rootless cosmopolitan is drawn in. He takes on men’s and women’s dress, the design and furnishings of their homes, their horses and coaches, staff and equipages. Nineteenth century readers must have gathered more from these lost social indicators than can we but they fascinate us through the sheer observation. And his meals, which put Mole and Ratty’s picnic to shame, leave one awestruck at the era’s appetites, at least for those who could afford to indulge them. Course after course, soups and fishes and meats and poultry and game (always after the beef: one does not eat the farmer after the gentleman) and desserts. And before them and with them and after them, drink. In one climatic dinner party Mr Jorrocks finally subsides briefly beneath the table only to re-emerge demanding that he be tied to the chair rather than abandon the procession of liquor.

I have not properly excerpted and without quotes, without rich helpings of all these hunts and houses, menus and wardrobes, not to mention the language, enslanged or otherwise, one cannot do the man justice. You can take it is as read but why do that when, so much better, you can read him.