He Knew, You Know

Charles Mackay and Victorian Catchphrases

Of late Bluesky along with much of the media has noted a new (pre-)teen expression, specifically 6-7 (now extended by -8-9). I have no wish (and honestly little interest) in pursuing this for GDoS. It is a fad among the tinies and I wish them luck. If nothing else it will ideally impart that vital lesson: if your once-prized expression, a positive baffler for the parents and kindred oldies, has reached the stage where a number of your peers lend themselves to intoning it with the current prime minister beaming and doing the hand gestures, it is time to bid it farewell. Smartish, and all.

A grown-up volunteered a far older instance of supposedly juvenile sloganeering: ‘Kilroy was here,’ from World War II. Unable to zip my own lip, I went back a further century to ‘’as you muvver lorst ’er mangle’ from c.1840.

For my sins, though perhaps apposite in this era of the iffy plagiarism machine, I failed a. to cite correctly, the phrase was ‘‘Has your mother sold her mangle’ often extended by ‘and bought a piano?’ and b. to credit the, if not originator (who knows with such street-born ephemera), but its collector. This was Charles Mackay a Scottish journalist whose two volumes of Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds appeared in 1841.

I wrote at reasonable length on the catchphrase in my Stories of Slang (2017). I offered music-hall, radio and TV intonations bringing them as near to publication date as I could. I gave pride of place to Mackay.

I posted but days ago, but fads fade, and I though I’d better get on with it. Which, I hope, is nice.

_______________

The mid-19th century was catchphrase heaven. Among them ‘all serene’, ‘go it you cripples (crutches are cheap)!’, ‘Jim along Josey’, ‘do you see any green in my eye?’ ‘who shot the dog?’ and ‘not in these boots.’ The origins were various but they sprang mainly from the music hall and from popular plays.

Some, however, had no obvious origin. Such was bender! which appears in 1812 and in effect meant bullshit! As defined in James Hardy Vaux’ Vocabulary of the Flash Language it was ‘an ironical word used in conversation by flash people; as where one party affirms or professes any thing which the other believes to be false or insincere, the latter expresses his incredulity by exclaiming bender! or, if one asks another to do any act which the latter considers unreasonable or impracticable, he replies, O yes, I’ll do it – bender; meaning, by the addition of the last word, that, in fact, he will do no such thing .’ An ancestor for modernity’s not. By 1835 bender has become over the bender, which apparently reflected a tradition that a declaration made over the (left) elbow as distinct from not over it need not be held sacred. The Victorians also used over the left, i.e. pointing with one’s right thumb over one’s left shoulder, implying disbelief.

Charles Mackay’s classic sociological study, Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions (1841) was especially interested in the phenomenon of catchphrases. Aside from Partridge’s Dictionary of Slang & Unconventional English (1936-84), which included ‘catchphrases’ in its subtitle, his study represents the great single concentration of the type. Mackay (1814-89) was a poet and journalist, who mixed such posts as that of the Times’ special correspondent during the American Civil War with the writing of song lyrics and of a wide variety of books, many on London or the English countryside. The first volume of Memoirs deals with a variety of such delusions – among them religious relics, witch and tulip manias, the crusades and economic ‘bubbles’ – and in the second turns to ‘Popular Follies in Great Cities’.

These, it transpires, are catchphrases, which are ‘repeated with delight, and received with laughter, by men with hard hands and dirty faces—by saucy butcher lads and errand-boys—by loose women—by hackney coachmen, cabriolet drivers, and idle fellows who loiter at the corners of streets. He also notes that each one ‘seems applicable to every circumstance, and is the universal answer to every question; in short, it is the favourite slang phrase of the day, a phrase that, while its brief season of popularity lasts, throws a dash of fun and frolicsomeness over the existence of squalid poverty and ill-requited labour, and gives them reason to laugh as well as their more fortunate fellows in a higher stage of society. London is peculiarly fertile in this sort of phrases, which spring up suddenly, no one knows exactly in what spot, and pervade the whole population in a few hours, no one knows how.’

His earliest example ‘though but a monosyllable, it was a phrase in itself’ was quoz which dated back to the 1790s. It seemed to have come from quiz, an eccentric person or an odd-looking thing, and its self from Latin quis, who. As the New Vocal Enchantress put it in 1791: ‘Hey for buckish words, for phrases we’ve a passion / [...] / All have had their day, but now must yield to quoz.’

Like many such phrases Mackay noted, quoz multi-tasked. It was all down to the user. ‘When vulgar wit wished to mark its incredulity, and raise a laugh at the same time, there was no resource so sure as this popular piece of slang. When a man was asked a favour which he did not choose to grant, he marked his sense of the suitor’s unparalleled presumption by exclaiming Quoz! When a mischievous urchin wished to annoy a passenger, and create mirth for his comrades, he looked him in the face, and cried out Quoz! and the exclamation never failed in its object. When a disputant was desirous of throwing a doubt upon the veracity of his opponent, and getting summarily rid of an argument which he could not overturn, he uttered the word Quoz, with a contemptuous curl of his lip and an impatient shrug of his shoulders.’

After quoz another monosyllable: walker! which worked as did bender! as an all-purpose teasing, dismissive exclamation which ‘was uttered with a peculiar drawl upon the first syllable, a sharp turn upon the last.’ It was short-lived, maybe three months, but served ‘to answer all questions. In the course of time the latter word alone became the favourite,’ and ‘if a lively servant girl was importuned for a kiss by a fellow she did not care about, she cocked her little nose, and cried “Walker!” If a dustman asked his friend for the loan of a shilling, and his friend was either unable or unwilling to accommodate him, the probable answer he would receive was, “Walker!” If a drunken man was reeling about the streets, and a boy pulled his coat-tails, or a man knocked his hat over his eyes to make fun of him, the joke was always accompanied by the same exclamation.’

Walker! shortened the slightly earlier Hookey walker! which otherwise functioned similarly. It came, said Jon Bee in 1823, from one John Walker, ‘an outdoor clerk’ at a firm in Cheapside; Walker had a hooked or crooked nose and was used by the ‘nobs of the firm’ to spy on his fellow employees. Those upon whom he spied naturally declared that his reports were nonsense and since they outnumbered him, they tended to prevail. Bee added that the word was accompanied by a gesture: ‘a significant upliftment of the hand and a crooking of the forefinger that [meant that] what is said is a lie, or is to be taken contrariwise.’

Bee’s slang collecting successor, Hotten, suggested ‘a person named Walker, an aquiline-nosed Jew’ (this was an assumption based on a stereotype: nose aside, he came from Westmorland and seems wholly English) who exhibited an orrery ‘the Eidoranion’ along which he would take a sight, which action, when used in slang, was the equivalent of a dismissive gesture. It was explained asa gesture of derision, made by placing the thumb on the tip of one’s nose and spreading out the fingers like a fan; thus the double sight, the same gesture, intensified by joining the tip of the little finger to the thumb of the other hand, which in turn has its fingers extended fanwise. Failing all that dexterity, Walker! was attributed to a magistrate named Walker, complete with the requisite nose.

Mackay also offered bad hat, which he links to an election in the London borough of Southwark, c.1838, in which one of the candidates was a well known hat-maker. As he campaigned he would single out any voter whose hat fell beneath the highest standards and declare: ‘What a shocking bad hat you have got, call at my warehouse and you shall have a new one.’ On the day of the election, as he gave his final speech, his opponents urged a hostile crowd to drown him out by chanting: ‘What a shocking bad hat!’ The phrase, first in its entirety, then reduced to ‘bad hat’, survived through the 19th century and, though it gradually declined, through the first half of the 20th. An alternative origin attributes the phrase to the Duke of Wellington, who on his first visit to the Peers’ Gallery of the House of Commons remarked, on looking down on the members of the Reform Parliament: ‘I never saw so many shocking bad hats in my life’.

Used as a cry of delight, triumph or defiance Flare up (and join the union)! had a solid background. It referred to the fires that accompanied the Reform Riots of 1832, notably, as Mackay noted, in Bristol which ‘was nearly half burned by the infuriated populace’. The flames were said to have flared up in the devoted city. Whether there was anything peculiarly captivating in the sound, or in the idea of these words, is hard to say; but whatever was the reason, it tickled the mob fancy mightily, and drove all other slang out of the field before it.’ The phrase was hugely popular: ‘It answered all questions, settled all disputes, was applied to all persons, all things, and all circumstances, and became suddenly the most comprehensive phrase in the English language.’

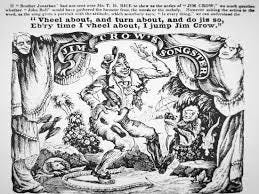

Mackay also included Jim Crow, which is better known in its 20th century incarnation as an adjective used to indicate racist laws . The name is found in an old Kentucky plantation song with the chorus ‘Jump Jim Crow’ and was hugely popularized when the ‘black face’ entertainer Thomas Dartmouth ‘Daddy’ Rice performed it in Louisville in 1828. It crossed the Atlantic, along with Rice, who sang it at London’s Adelphi theatre in 1836, in a ‘farcical Burletta ’ [i.e. short comic opera] entitled ‘A Flight to America, or, Twelve Hours in New York’. The lexicographer Schele De Vere, writing in 1871, saw it as pure Americana: ‘We have no ballad and no song that can be called American. The nearest approach [...] was the dramatic song Jim Crow, brought out about the year 1835 by an enthusiastic Yankee on the boards of a theatre in New York; it created a sensation, for it was new in form and conception, and no doubt rendered still more attractive by the strange guise in which it was presented. [...] For a time this African inroad drove nearly every other song from the publisher’s store and the drawing-room.’

Mackay was not amused, and termed it ‘a vile song.’ Rice ‘sang his verses in appropriate costume, with grotesque gesticulations, and a sudden whirl of his body at the close of each verse. It took the taste of the town immediately, and for months the ears of orderly people were stunned by the senseless chorus — “Turn about and wheel about, / And do just so– / Turn about and wheel about, / And jump, Jim Crow”.’ Minstrel shows, parading every racial and thence racist trope, lasted a good real longer, proving to be one of the world’s greatest entertainment favourites until TV’s ‘Black and White Minstrel Show’ of the 1960s.

There he goes with his eye out! (which could also take the female ‘she’ and ‘her’) was one of a number of exclamations aimed at such passers-by as the speaker found amusing. Mackay was unimpressed, and termed the phrase ‘most preposterous. Who invented it, how it arose, or where it was first heard, are alike unknown. nothing about it is certain, but that for months it was the slang par excellence of the Londoners, and afforded them a vast gratification. “There he goes with his eye out!” or “There she goes with her eye out!” [...] was in the mouth of everybody who knew the town. The sober part of the community were as much puzzled by this unaccountable saying as the vulgar were delighted with it. The wise thought it very foolish, but the many thought it very funny, and the idle amused themselves by chalking it upon walls, or scribbling it upon monuments.’

Similar shouts were framed as questions. Does your mother know you’re out? ‘was the provoking query addressed to young men of more than reasonable swagger, who smoked cigars in the streets, and wore false whiskers to look irresistible.’ In other words, young men who claimed the affectations of manhood without having earned them by age. It was much used by women who wished to counter an impertinent male gaze, and many a leering youngster was ‘reduced at once into his natural insignificance by the mere utterance of this phrase.’

Still with mum, we find Has your mother sold her mangle? (a foretaste of the later, and inescapably if unquantifiably suggestive if not exactly obscene How’s your mother off for dripping? a phrase that some claim is the correct response to the traditional Cockney greeting Wotcher cock!). The mangle can be extended by ‘and bought a piano’ or rephrased as the query: ‘does your mother keep a mangle?’ This ‘impertinent and not universally apposite query’ gained, in Mackay’s words, only a ‘brief career,’ being ‘not of that boisterous and cordial kind which ensures a long continuance of favour.’ Its problem, he felt, was that you couldn’t use it to old people, whose mothers had long passed on.

Seemingly simple was who are you? which was delivered aggressively and met with an equally aggressive response, ‘who are you?’ Whether this led to fights is not recorded. Mackay told how ‘this new favourite, like a mushroom, seems to have sprung up in a night, or, like a frog in Cheapside, to have come down in a sudden shower. One day it was unheard, unknown, uninvented; the next it pervaded London. Every alley resounded with it; every highway was musical with it.’ A multipurpose line, it applied to anything the speaker wished.

__________________

Ta-ta for now.

The headline was taken from a great Brit. comedienne, Hylda Baker of whom you may know but just in case (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hylda_Baker). Her own catchphrase was 'She knows, y'know' (to be spoken in Lancashire accent) and referred, I believe, to her foil, the silent Big Cynthia, played by a succession of men in drag. I should have added a pic.

Oh yes. I cannot speak for your version of St Custard's, but we (St Hugh's, named for a blood libel) had a cut-out/over-ride: ‘Baggy no par!’ (Bags I no part!) which freed one from any involvement. And indeed, never thought of it before, but the day we left prep school such childish things were thrown off and never voiced again. (Though GDoS records adult use of 'bags/bagsy' as a demand)