[Another dip into Sounds & Furies / Bitching, my attempt to elicit the relationship of women and slang. If my last post dealt with the Cockney, and specifically the male of the type ’Arry, this excerpt takes a look at the distaff side. Though not the real thing, but its hyper-fantasised representation as found on stage in the late 19th century music halls. Some played it straight, others, notably Vesta Tilley, appeared in male drag, usually that of a swell, but for my purposes I looked mainly at a couple: Marie Lloyd and Bessie Bellwood. They too could take a turn in drag, but mainly they played it femme. If they had a common role it was that of the donah, the coster’s girl. Her character was doubtless mutable but like her Australian 'cousin' the larrikiness, and America's g’hal she had a uniform. In 1859, defining the once congratulatory word tart, John Camden Hotten put it thus:

Tart, a term of approval applied by the London lower orders to a young woman for whom some affection is felt. The expression is not generally employed by the young men, unless the female is in ‘her best,’ with a coloured gown, red or blue shawl, and plenty of ribbons in her bonnet — in fact, made pretty all over, like the jam tarts in the swell bakers’ shops.

And she could never, ever sport too many ostrich feathers.

____________

Then a swell from the West winked his blinkers once at me,

And in course I tips ’im back a civil wink.

I was eating of some winkles from a paper in my ’and,

Which I offers ’im and then he stands a drink.

Then ’e says, ‘If you will fly with me I’ll put yer on the stage,

Where yer know the corster business now, is getting quite the rage!’

‘What!’ says I, ‘You teach yer grandmother, my covey, to suck eggs,

D’yer think I’d ever go upon the stage and show my legs?’

Marie Lloyd ‘Garn Away’ (1892)

Marie Lloyd (Matilda Alice Victoria Wood) was undoubtedly the queen of the halls, one of the limited number of ‘stars proper’ of the variety stage who according to the London Society magazine, could ‘almost be counted on one’s fingers.’[1] Born in 1870 she launched her career in 1884, appearing, as ‘Bella Delamere’ at the Grecian Music Hall, attached to the Eagle (the City Road pub, still on site, that gained immortality in the nursery rhyme ‘Pop Goes the Weasel’). Thereafter she came on as herself and moved swiftly up the bill. By 1886 she was earning £100 a week (in 2019 purchasing terms around £12,500). At her pre-World War I peak she was a worldwide star. She toured Australia and the States. The Los Angeles Times termed her ‘The Queen of Comedy Song’ and ‘a cartoonist of London types’ [2] . Only in her unfortunate choice of husbands, there were three and each was to some extent abusive, did what seemed like infinite success elude her.

As noted in the ODNB ‘Lloyd articulated the disappointments of working-class life, especially those of women.’ [3] Less sentimental, à la Albert Chevalier, than grimly realistic, she made it clear that a donah’s lot could be a far from happy one: faced by domestic violence and financial worries her escape was drink or perhaps a lover. After all, as one of her most celebrated songs proclaimed ‘A Little of What You Fancy Does You Good’. But as that title and many others make clear, the great over-riding theme was naughtiness, even smut, though the latter was never directly spoken. ‘I always hold in having it if you fancy it / If you fancy it, that’s understood’ ran the chorus of ‘A Little of What You Fancy’ and for slang fans, both ‘have it’, and ‘it’ could easily run to alternative interpretations.

‘She could play out the contrast between the persona of a song and her own stage presence: as a cockney child in the country, giggling as a bull ‘wagged 'is apparatus’, she wiped her nose on her sleeve and kicked aimlessly, dressed in one of the elaborate gowns she loved; she could add a top-spin of lewdness to the most innocent lyric and slip into amused contemplation of her own naughtiness; the title of one of her first commissioned songs, “When you wink the other eye”, symbolized her stage presence—the sense of sharing a secret with her audience rather than simply a smutty joke.’ [4]

T.S. Eliot, in the Era (1922), turned a blind eye to smut, claiming that ‘There was nothing about her of the grotesque; none of her comic appeal was due to exaggeration’ [5]; His poem The Waste Land owes much to the music hall. Others saw otherwise: for many, her whole shtick was exaggeration: sidelong glances, winks, grimaces...the popular gamut of the nudge-nudge, wink-wink style that underpins so much British humour. During her Australian tour of 1901 Melbourne’s Table Talk noted her ‘blue’ songs, but, mixing up a couple of metaphors, added that while her lyrics ‘get pretty close to the knuckle [they] never jump over the fence.’ [6]

Her songs, unsurprisingly, are filled with slang. Well over 250 words or phrases. They are, by slang standards, almost wholly bland. Just as in her songs as a whole she might dance along the edge of obscenity, but it was all in the audience’s mind. But if this was run-of-the-mill slang, it was exactly what her audience knew and what they used at home and work. It helped make her one of them and it shouldn’t be surprising that a good 30% of the slang she used overlapped with her fictional contemporary, E.J. Milliken’s Cockney ‘chap’ par excellence, ‘’Arry’, whose slangy ‘ballads’ appeared in Punch from 1878-1892 and whose given name became shorthand for any of his type.As befitted any Cockney worthy of the name, there was rhyming slang: almond rock [frock], darby kelly [belly], dicky dirt [shirt], God forbid [kid/child], heart of oak [broke / poor], how-do-you-do [a to-do, a problem], tealeaf [thief] and threepenny hop [shop]. It is just possible that the first of these was used for its alternate, and far better known meaning, ‘cock’. There was, as one might expect, donah: but the speaker, even through her lips, was male, telling her admiringly, ‘Straight, you are a blooming “slap-up” little donah’. [7] As for blue, that was there, but only in the most patriotic of disavowals: ‘Let them keep the blue, they’re blue enough, French papers so obscene, / But let them keep their hands off English women’s lives so clean.’ [8] A little bit of predictable jingoism from the girl who brought fans ‘The Coster Girl in Paris’ and there confessed that ‘if they'd only shift the ’Ackney Road and plant it over there, / I'd like to live in Paris all the time!’ [9]

Obscenity – ‘whatever gives an aged and impotent judge an erection’ – like beauty, allows for a very subjective assessment. In the music hall context it was hard to miss the nods and winks, of course, but one had to be a dedicated bluenose to see actionable ‘filth’ in the words she used. By slang’s standards her vocabulary was anodyne. She mentions hot stuff and a bit of crackling (as well as bit of goods and bit of stuff) which meant a young woman and claims herself as warm and ‘a little bit fruity’; a saucy joke was spicy; there are spooning and yummy-yum, two of the era’s terms for love-making. Perhaps the nearest she gets to out-and-out smut is agility as in The Wrong Girl (1895): ‘The day your gee-gee stumbled there / And threw you off, you know. / But you were up and on again / As agile as can be’ / I said, ‘Excuse me, sir, you’ve not / Seen my agility’. The ‘riding’ backdrop aside, even this required a bit of foreknowledge. It mimicked a joke that was published in 1888, but was probably a good deal older: ‘A young lady was out riding, accompanied by her groom. She fell off her horse and in so doing displayed some of her charms; but jumped up very quickly and said to the groom : “Did you see my agility, John?” “Yes, miss,” said he, “but we calls it cunt in the kitchen!”’ [10]

Drinks included fizz and cham (champagne), b. and s. (brandy and soda, and pongelo (beer) Half seas over was drunk and a drink was a drain or a sherbet. There was also what might be termed swearing, but of the mildest sort: bally, blessed, blooming, blow!, Jerusalem!, lumme!, no fear!, not much!, rather! and s’elp me bob! Nothing, surely, to trouble the local watch committee. But the professionally offended live for offence, however thin the evidence, and Lloyd was not immune from attack. In 1894, when the license of one of her favourite venues, the Oxford Music Hall came up for its annual renewal, it was strongly opposed.

The self-appointed censors specified two songs as ‘objectionable’. Both seemed to depend upon knowledge of the forbidden. One, sung by Lady Mansel (Lillie Ernest before her marriage into the aristocracy) had the chorus ‘What I saw I must not tell you now’; and referred to the ‘saucy’ results of various clothing malfunctions, high winds and mistaken entries into the men’s dressing room. The other was Lloyd’s ‘What’s That For?’ otherwise known as ‘Johnny Jones’. In this case Lloyd, dressed as a schoolgirl, offered such faux-naive verses as

Pa took me up to town one day

To see the shops and sights so gay

Oh how the ladies made me stare

They nearly all had yellow hair

And one of them - Oh what a shame

She called Pa ‘Bertie’ it’s not his name

Then went like this (kissing sound) and winked her eye

And so I said to Pa, ‘Oh my!’

and a chorus that had the ‘schoolgirl’ asking:

‘What's that for, eh? Tell me Ma

If you don’t tell me I'll ask Pa’

But Ma said, ‘Oh it’s nothing, shut your row’

Well, I've asked Johnny Jones, see,

So I know now.

There were also problems with another verse, in which ‘Ma’ seemed to be making baby clothes. There were further objections to the flouncing of skirts by one singer, and the lifting of a female performer so that ‘she was entirely exposed’. As the self-appointed censor invariably demands, multiple visits were necessary to ascertain all this ‘obscenity’. On one of these Madge Ellis, again as a schoolgirl, used the lines ‘You show me yours fust, and I’ll show you mine’. The offending item was a bruise, but it was too far up the thigh for propriety to remain silent. A gentleman witness complained that a young woman ‘ogled’ him. This time Marie Lloyd’s ‘He knows a good thing when he sees it’ came under the disapproving glare.

My dear Uncle Sam is a jolly old cock

Who knows a good thing when he sees it

He's right up to snuff, he can tell you what’s o’ clock

And he knows a good thing when he sees it.

He once saw an up-to-date play in the West

And sweet Chorus ladies scantily dressed

Round to the stage door later on did he roam

And found ‘something choice’ coming out, going home

Chorus: Then he stood it a supper at Scotts

And bought it a bottle to please it

For its dear little waist

Seemed to tickle his taste

And he knows a good thing when he sees it

There was more of the same and one cannot deny that such lyrics were nothing if not suggestive. (‘It’ was long established in the sphere of sex; this was seemingly the first occasion on which the word was used to mean a young woman). Perhaps the most interesting line referred to Lloyd’s view of a gentleman’s ‘first class’ ticket, perhaps cognate with her song title ‘She’d Never Had Her Ticket Punched Before.’

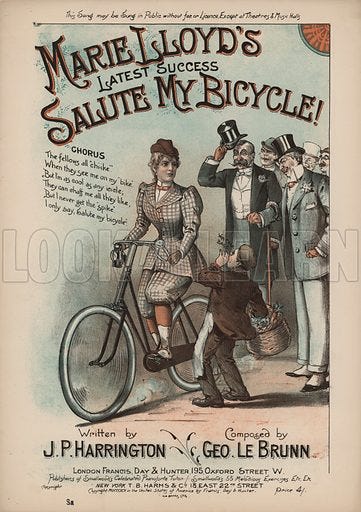

Another lyric, that of ‘Salute My Bicycle’, in which the singer wore the new ‘rational dress’ (notably the ‘bloomer suit’) was deemed ‘difficult’.

You see I wear The Rat’nal Dress,

Well how do you like me? eh, boys?

It fits me nicely, more or less,

A little tasty! eh, boys?

When on my ‘bike’ I make a stir,

Girls cry, ‘My word!’

Men cry, ‘Oo-er!’

And in this garb they scarce can tell,

Whether I’m a boy or ‘gell’.

Chorus: The fellows all ‘chike’,

When they see me on my ‘bike’,

But I'm as cool as any icicle;

They can chaff me all they like,

But I never get the ‘spike’,

I only say, ‘Salute my bicycle!’

Whether this was Lloyd’s self-promotion as ‘tasty’ and in later verses ‘sultry’, ‘saucy’ and ‘tricky’ that worried the censors is unstated. Perhaps it was the implied transvestism of garments that defeated gender specificity, or the dismissive slogan that was in effect a euphemism for ‘kiss my arse’.

Lloyd had no direct input to the hearing (the Oxford survived for a further year) but soon afterwards she was summoned before a London County Council committee and asked to sing some songs. As the Sporting Times’ historian J.B. Booth put it in his memoir Pink Parade [11]:

Marie sang them, as a Sunday School child would ‘speak its piece’—without wink, laugh, or glance—and they were supremely and utterly proper—and dull. The deputation rose to leave, but she stopped them. ‘Now, she said, ‘you've had your show. I’ll have mine. I’m going to sing you a couple of the songs your wives sing.’ And she sang them, ‘Queen of my Heart,’ and ‘Come into the Garden, Maud,’ which quite suddenly acquired incredible improprieties.

‘There!’ she said triumphantly, ‘if you can stand that sort of stuff in your homes I don't think there's anything much wrong with my little parcel!’

She would never convince those whose whole satisfaction depended on interfering in the pleasures of others. In 1912 she was banned from the Royal Variety Performance (had Edward VII still been on the throne things might have been different). The solution was simple: she booked another theatre for the same night and filled every seat.

Marie Lloyd wasn’t, of course, the donah’s only avatar. A number of singers positioned themselves along the spectrum of Cockney womanhood. One being Jenny Hill (born Elizabeth Thompson), whose unfettered energy won her the name ‘The Vital Spark’ and who sometimes appeared in drag as a Cockney coster, inevitably named ‘’Arry’. Her act had plenty of slang, which did her no good on her US tour where unappreciative audiences had to be provided with a printed glossary.

Among the other ‘donahs’ were Lottie (properly Charlotte Louisa) Collins, whose style is best summed up in her hit ‘Ta-ra-ra-boom-dee-yay!’ and in her on-stage look: a hugely-brimmed ‘Gainsborough’ hat[12] and the sort of skirt and petticoats usually associated with that naughtiest of dances ‘the can-can’, and Florrie Forde (Flora May Flanagan), whose best-known tunes included ‘Down at the Old Bull and Bush’ and the World War I staple ‘Tipperary’. Forde was another splendid dresser, her tall, imposing figure bedecked with ostrich plumes, capes, trains, high heels and a good sprinkling of sequins. Plus a jewelled cane. As a modern commentator put it, Forde’s delivery ‘was that of a benevolent sergeant-major addressing raw recruits.’

If Lloyd was the plucky trier – accepting of bad times but always up for the possibility of good ones – her antithesis was surely Bessie Bellwood. Bellwood was full-on hen party (coined in 1879 as an all-female gathering, but only attaining its present sense in the late 20th century): unrestrained, noisy, quite probably terrifying every passing male. Born Catherine Mahoney in 1856, she took her stage name in 1876. She was working as a rabbit-puller or skin dresser in a Bermondsey factory when she made her debut at the local hall.

She was, the story runs, supposed to be performing on the ‘zithern’, today’s zither. The audience was less than receptive and the chairman, supposed to keep order, was unable to quell the hecklers. According to the indefatigable J.B. Booth, things proceeded thus:

Singling out a ringleader, a gigantic, heavy animal with the appearance of a brewery drayman, ‘You, sir!’ cried the little man, ‘you—in the grey flannel shirt—will you allow the lady to proceed?’ ‘No!’ bawled the brute, and the gallery shrieked its delight.

This was the last straw for the signora...So, slinging the zithern into the wings, she advanced to the footlights, and, arms akimbo, after calling the chairman ‘an old messer,’ told him ‘For God’s sake shut it, if that’s all you can do for a living!’ and proceeded to take the matter into her own hands.

Ignoring the rest of the audience as unworthy of serious attention, she went direct for the brewery drayman. He was no mean lord of language: his bright young lexicon was crammed to overflowing with recondite phrases culled from east and south, from Billingsgate to Limehouse Hole, from Petticoat Lane to Whitechapel, from eel-pie shop and penny gaff, from doss-house, tavern, court and street, and he stood up to his opponent like a man.

But after a fierce interchange of two full minutes he fell back gasping, dazed, speechless and, worst of all, he had used up his vocabulary, and could but start all over again.

Then she really began.

She started by announcing that she was going to ‘wipe down the bloomin’ hall with him an’ make it respectable’—and she did it. His very pals sitting near him edged away, as though afraid of catching something from such a mass of vileness.

Every phrase she flung at him hit an invisible bull’s- eye. The last name seemed ideal—until the next one appeared and seemed the one he ought to have been christened by.

And then she gathered herself together for one supreme effort, and hurled at him a brief description of his ancestry, his present, his future, so sharp with insight, so all-embracing, that the audience shivered in the presence of the pariah. [13]

As London Society put it in 1896, Bellwood was ‘the character singer par excellence of the halls [...] a lady whose great talent is backed by an amount of impudence that is, even for a Cockney, nothing less than astounding. Her ready wit never fails to stand her in good stead, and no matter what topic she may light upon her comments are always amusing and to the point. No one who has ever heard her engage in wordy warfare with her audience (a reprehensible custom to which this fair artist is unhappily too much addicted) has ever heard her come off anything but victorious.’ In 1888 she threatened a libel suit against an accuser who claimed that her songs contained unladylike lyrics. It does not seem to have come to trial, a pity, since the court was thus deprived of what Ralph Nevill, in The Man of Pleasure (1913) termed ‘Miss Bellwood’s considerable powers of trenchant repartee.’

Her signature song, ‘Wot cher Ria’ pretty much summed her up. It was, how not, as slangy as one might wish:

I am a girl what’s a-doing very well in the wegetable line

And as I’d saved a bob or two, I thought I’d cut a shine

So I goes and buys some toggery, these ’ere wery clothes you see

And with the money I had left, I thought I’d have a spree

So I goes into a Music Hall, where I’d often been afore

I don’t go in the gallery, but on the bottom floor

I sits down by the chairman, and calls for a pot of stout

My pals in the gallery, spotted me, and they all commenced to shout.

Chorus: What cheer Ria! Ria’s on the job

What cheer Ria, did you speculate a bob?

Oh Ria she’s a toff and she looks immensikoff

And they all shouted ‘What cheer Ria!’

Of course I chaffed them back again, but it worn’t a bit of use

The poor old Chairman’s baldie head, they treated with abuse

They threw an orange down at me, it went bang inside a pot

The beer went up like a fountain, and a toff copt all the lot

It went slap in his chevey, and it made an awful mess

But what gave me the needle was, it spoilt my blooming dress

I thought it was getting rather warm, so I goes towards the door

When a man shoves out his gammy leg, and I fell smack upon the floor.

Chorus: [as above]

Now the gent that keeps the Music Hall he patters to the bloke

Of course they blamed it all on me, but I couldn’t see the joke

So I up’d and told the governor as how he’d shoved me down

And with his jolly old wooden leg, tore the frilling off my gown

But lor bless you! It worn’t a bit of use, the toff was on the job

They said outside! and out I went, and they stuck to my bob

Of course I felt so wild, to think how I’d been taken down

Next time I’ll go in the gallery with my pals, you bet a crown.

She was the darling of the era’s Sporting Times, better known as the ‘Pink ’Un’ (like the Financial Times it used pink stock) and the home of such pseudonymous hacks as the Pincher, the Shifter, the Dwarf of Blood, Rooty-Tooty and many others. They called her the Queen of Song and the One and Only, among many other encomia. They hymned the joys of the Strand, especially Romano’s restaurant, when that thoroughfare was London’s gaudy carnival midway for toffs and proles alike. Bellwood gravitated between the two. Her lover was the indolent Kim Mandeville, Duke of Manchester and she was not above knocking down, then thrashing a cabbie who made a dubious crack at His Lordship’s expense. The American press was less indulgent. When in 1892 Mandeville died aged only 39, worn out and broke, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer belied its nation’s much-touted egalitarianism, sneering at Bessie as ‘his mistress...a big, muscular, barmaid type of young woman’ and implying that it was she who ran through his fortune (though at the same time they complained that he had lived off hers). Not that they had any more time for ‘the dissolute duke...the dead beat debauchee...who had disgraced an honorable name by the most disgusting excesses.’ However their real rancor was reserved for Mandeville’s American wife. She should have known better, being an American girl; ‘low-born and low-bred’ Bessie, in her ‘gross depravity and systematic impurity’ was merely doing what she had been brought up to. [14]

She died in 1896, victim of her unstintingly Bohemian lifestyle, and the alcoholism it engendered. At the same time she was generous to the poor, giving away much of what she earned. Her estate was worth a mere £125 (worth around £20,000 today), a pittance for someone who would have earned that and more every night. The funeral procession drove through teeming crowds from Fulham Road near her West London home to Leytonstone’s catholic cemetery in the East.

London’s Pall Mall Gazette was one of many obituaries:

She played one part — herself; and it was Bessie Bellwood playing herself that the crowd went to see. She had not a touch of pathos. No one ever saw her serious on the stage— to have done so would have been a shock to every tradition. [...] Music-hall fashion has advanced and it left Bessie Bellwood behind it. Mr. Albert Chevalier has made the stage coster a namby-pamby individual, seeking after something better than his native life and surroundings, and he has his hosts of imitators, male and female. Bessie Bellwood took that phase of life which suited her powers best—

The Low, Rowdy, Fighting, Hair-tearing Girl of the lowest courts in the East-end, a creature all fringe and mouth, and into her, as into all her characters, she thrust her own strong individuality. A better actress would have concealed herself in the character she portrayed, and have missed the popularity which Bessie Bellwood enjoyed. Bessie Bellwood herself—the woman we knew not only on the stage, but in what was euphemistically called her private life, her appearances in the courts, and her squabbles with her landlords and her agents—came out strongly in everything she touched.

Like many another music-hall favourite she owed nothing of her popularity to her voice. [...] Her songs served only as skeletons, round which, and in the middle of which, and, indeed, at both ends of which, she could interpellate her ‘patter’; and in this ‘patter’ was her secret of success. She possessed an inexhaustible fund of slang, which flowed from her lips in an incessant stream—‘back-slang,’ which must have been utter mystification to many such people as now take their sisters to the West-end halls, but which any one coming into contact with East-end life could easily translate.[15]

Ta-ta, ’Ria!

___________

[1] London Society LXX (Jul-Dec 1896) p. 31

[2] L.A. Times 29 Mar. 1914 pt 3 p.1

[3] ODNB ‘Marie Lloyd’

[4] ODNB ‘Marie Lloyd’

[5] ‘Marie Lloyd’ in T. S. Eliot, Selected Essays (3rd edn., London, 1951) p.452

[6] Table Talk (Melbourne) 23/05/1901

[7] T. & G. LeBrunn [perf. Marie Lloyd] ‘Come Along, Let’s Make Up’ (1901)

[8] 1900 E.W. Rogers [perf. Marie Lloyd] ‘The Red and The White and The Blue’

[9] O. Powell & F. Leigh [perf. Marie Lloyd] ‘The Coster Girl in Paris’ (1912)

[10] ‘An English Popular Story’ in Kruptadia (1888-1911) vol. IV 394-5

[11] J.B. Booth Pink Parade (1933) p. 162

[12] the original being that painted by the artist to adorn Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire in 1787 and re-adopted by the contemporary Gaiety Girls

[13] J. B. Booth ‘Master’ and Men (1927) p. 105ff

[14] Seattle Post-Intelligencer (WA) 28 Aug. p.4/1

[15] Pall Mall Gazette 25 Sept. 1896 p.7/3

I came to Bessie through the Sporting Times, where she was undoubtedly their favourite diva, and probably for her unashamedly raffish lifestyle. No compromises.

They sound so much fun! I went to some show in London once, decades ago now, that was supposed to be Victorian music hall. It was somewhat camp but more twee, really - the very best of it having the feel of the very weakest of Flanders and Swann. From this post I get a sense that the real thing was more exciting. What I wouldn't give to see a Bessie Bellwood show - and it sounds like she'd do all right on the standup circuits of today. Thanks!