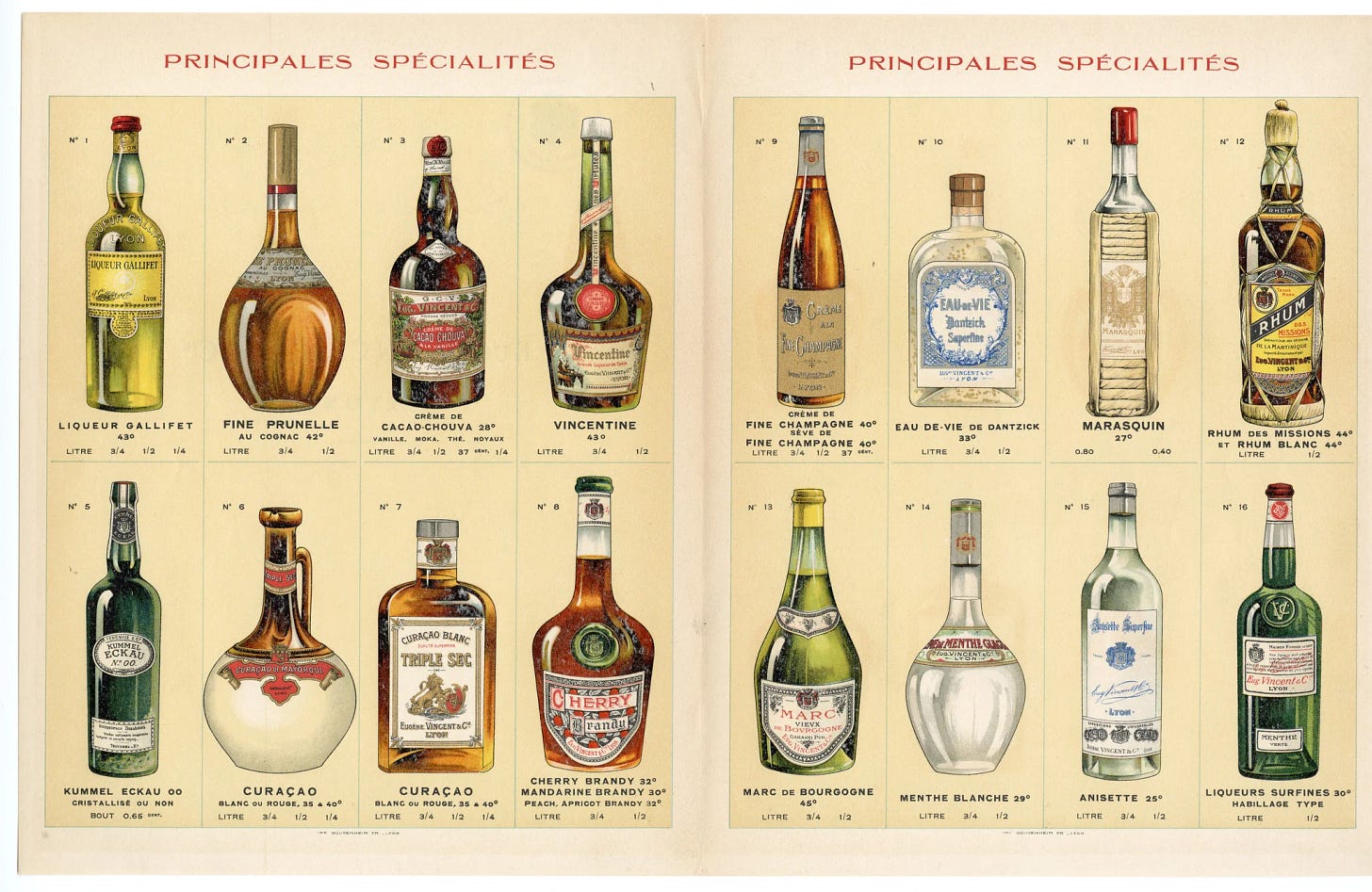

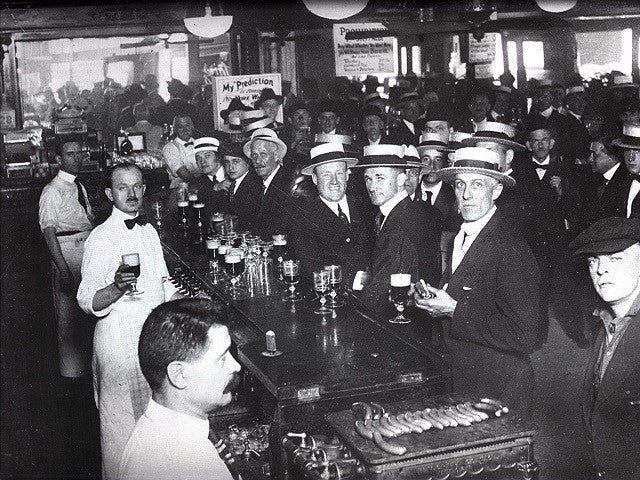

A search on alcohol or liquor or simply ‘a drink’ reveals that slang offers nearly 950 terms. This is not surprising. Along with sex and crime, alcohol, its consumers and consumption and its usually deleterious effects, provide the very essence of the counter-language. Humankind, as T.S. Eliot noted, cannot stand too much reality, and liquor definitely takes the edge off, even if it can take us straight back to sex and crime. Further enquiries for the specifics beer (534), whisk(e)y (272), wine (200), gin (192) and brandy (117) more than doubles that total. Over 2,200 terms. (Not to mention the 1800+ drunks). Too many for proper consideration here. Apologies to those who will thus miss their tipple of choice, but let us concentrate mainly on a single subset: mixed drinks, for which slang has always had a partiality. (Apologies too to henryjeffreys.substack.com who will almost certainly find a whole bonded warehouse brimming with errors.)

The word ‘cocktail’ first appears in 1803 when its drinker noted that it was ‘excellent for the head’ and went on to down a second. He does not specify the ingredients although three years later the drink is defined as ‘a stimulating liquor, composed of spirits of any kind, sugar, water, and bitters.’ The stimulus we can take for granted, while the idea of blending alcohol either with another variety or with ingredients that modified the basic taste, was hardly new. The 16th century, when the recording of such recipes begins, offers stamp-in-the ashes (‘some fancy drink’ essays Partridge), for which, regrettably, neither ingredients nor indeed etymology have been discovered.

To commence, some proper names. Aristippus referred to two drinks. The first being Canary wine (produced in the Canary islands), another name for the fortified wine that was known as sack (most likely from Spanish sacar, to draw out, i.e. from the barrel) and subsequently as Malaga or today’s sherry. The second definition is less appealing: a diet drink, made of sarsparilla, cinchona bark (a.k.a. Jesuit’s bark and the basis of quinine) and other ingredients, available at certain coffee houses. Why it was named for Aristippus (c.435–366BCE), a Greek philosopher who founded the rigorously hedonistic Cyrenaic school of philosophy is unknown, though his supposed portrait shows a certain jauntiness. It was presumably a hat-tip from a classically educated age to the school’s basic belief: that pleasure was what counted. And by pleasure they didn’t mean simply the absence of pain, but active, immediate gratification. Physical pleasure, in the here and now; emotional pleasure worked, but lacked that all-important sensuality. Have another.

Another liquorous mixture, a hot drink of small beer mixed with brandy, plus lemon juice, spices and sugar, was a Sir Cloudesley. Much loved in the Royal Navy it took its name from that of Sir Cloudesley Shovell (1650–1707), a notable British admiral who was knighted for his suppression of piracy.

Catherine Hayes was a drink made of claret, sugar, nutmeg and orange. The general belief is that the lady in question was an Irish songbird, vastly popular in Australia (where another singer, Nellie Melba, would come to name a foodstuff too). It was Hayes (c.1818-61) who was the first ever singer of ‘Kathleen Mavoureen’, that classic Irish love song in its home town of Dublin. (The song, with its line ‘It may be for years, it may be forever’, came in slang to define an indeterminate prison sentence). The sweet-voiced soprano was most likely the authoress of the sweet concoction, but there is a possible challenger: an earlier Catherine Hayes (1690–1725) who murdered and dismembered her lover (body parts into a nearby pond, head into the Thames) after deliberately rendering him insensibly drunk. Hayes suffered a more than usually miserable death: sentenced to be burned at the stake, so hot were the flames that the executioner was unable to perform the usual preliminary mercy killing by strangulation. Instead she only died when a bystander threw a heavy lump of wood, crushing her skull.

The effects of Sneaky Pete (there is no pertinent Peter on record, though there may be a link to late 19th century peter, drugged or adulterated liquor) ‘sneak up’ on the consumer. Best-known as cheap, rotgut wine (rotgut itself covers all sorts of third-rate drink and goes back to 1597) it has also been used to describe marijuana mixed with wine and, terrifyingly but presumably effectively, a form of spirit distilled from household chemicals. His feminine companion is red Biddy, usually equated with cheap wine and also found as red Lizzie. The name can also apply to meths (of which more below), as included by James Joyce in his novel Finnegans Wake when he mentions one Treacle Tom who ‘slept in a nude state, hailfellow with meth […] blotto with divers tots of hell fire, red biddy, bull dog, blue ruin and creeping jenny’. (Blue ruin being gin, as well as applejack or the hangover that follows either. None of the others, sadly, have been explained although creeping jenny is elsewhere the plant lysimachia nummularia, known for its aggressive colonisation of all available soil).

Proper names aside, there are also geographical links. For instance Brummagem wine: any adulterated or mixed drink. This, with its negative stereotyping of Birmingham, is an extension of the older form, Bromicham: ‘particularly noted a few years ago, for the counterfeit groats made here, and from hence dispersed all over the Kingdom.’

Australia offers three off-brand uses of champagne, none of which much resemble the French original. There is the Domain cocktail, a mixture of petrol and pepper allegedly once popular among Domain dossers or down-and-outs, in the Sydney Domain, a city park which was popular for speech-making and frequented by the unemployed and the alcoholic. For Northern Territory or bush champagne, stereotyped with racist glee as a favourite tipple among Native Australians, see below.

A King’s peg was a champagne cocktail that mixes champagne with brandy. The King is self-evident and its date suggests that the monarch in question was Edward VII. Edward also modified the usual recipe, substituting whisky for the brandy and adding Maraschino and angostura to create his own ‘Prince of Wales cocktail’. As for peg, this either moralises on the idea that each drink was one more peg, i.e. nail in the drinkers coffin, or takes us back to the 17th century’s tankards, wherein peg referred to ‘one of a set of pins fixed at intervals in a drinking vessel as marks to measure the quantity which each drinker was to drink’ (OED). The King, then Prince of Wales, also took responsibility for the use of boy to mean champagne. As chronicled by Arthur Binstead in A Pink ’Un and a Pelican (1898) ‘At a shooting party of His Royal Highness’s [in 1879], the guns were followed at a distance by a lad who wheeled a barrow-load of champagne, packed in ice. The weather was intensely close and muggy, and whenever anybody felt inclined for a drink he called out “Boy!” to the youth in attendance; the frequency with which this happened leading to the adoption of the term.’

Finally, and perhaps inevitably, a pun: a war cry, a mixture of stout and mild ale, played on the Salvation Army newspaper The War Cry and the belief that while the Army spoke ‘stoutly’ it used only ‘mild’ terms.

No-one pretended that this stuff didn’t have a kick: wasn’t that the point? Rough whiskey might be spill-skull, bust-skull, pop-skull, swell-skull and swell head. Australia offered blow-my-skull-off, which mixed wine, opium, cayenne pepper and rum; it doubtless did just that and was much prized at the mid-19th century gold diggings; an alternative recipe mixed boiling water, sugar, lime or lemon juice, porter, rum and brandy. A shake-up was a form of cocktail, made from a variety of liquors, plus wine.

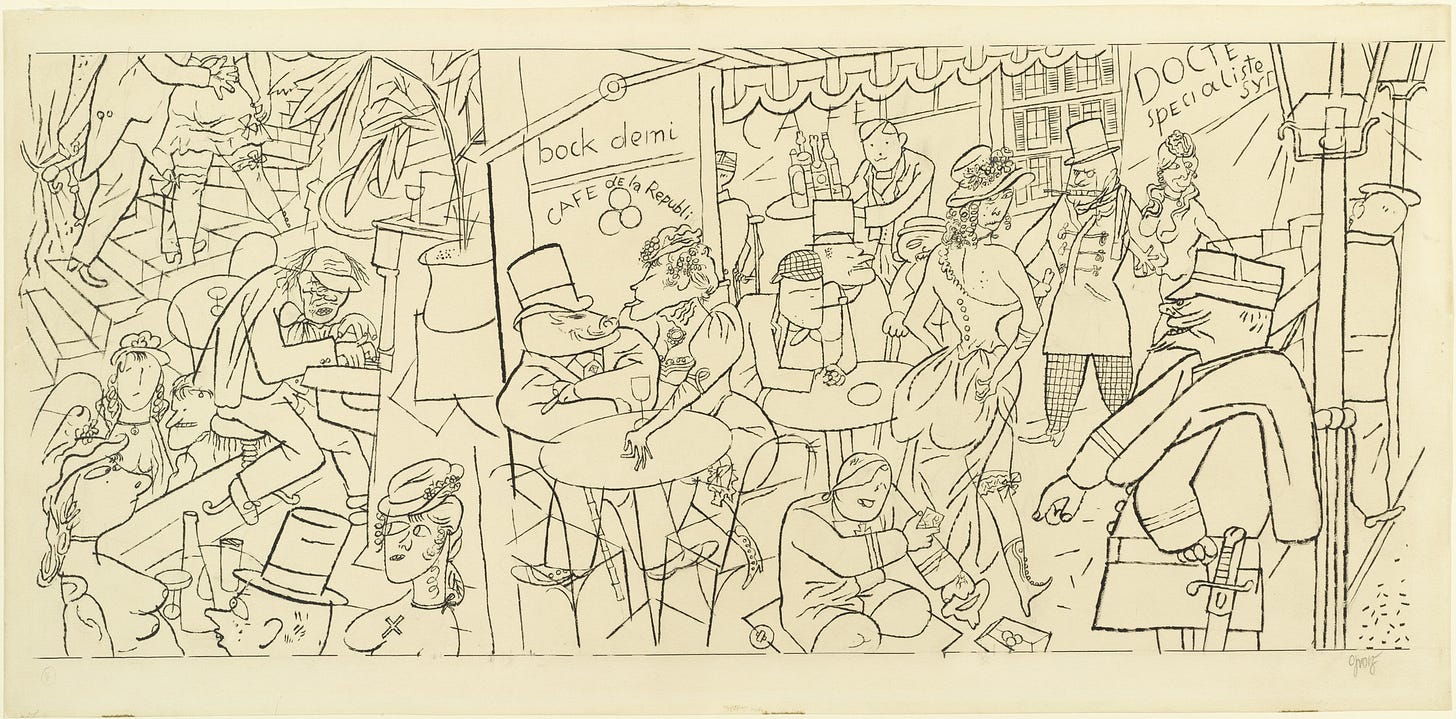

After which, one needed a corpse reviver, another non-specific mixed drink, tossed back in the hope of curing a hangover. It was usually listed among typical mid-19th century ‘American drinks’, all luridly innovative to the visiting Brits. There was even a comic song, ‘The American Drinks’ created by the music-hall star Arthur Lloyd (1840-1904): ‘I suppose you've all tasted American drinks at one time or other,’ he asked his audience, ‘curious names they have tho’, for instance there's...

A stone-fence, a rattlesnake, a renovator, locomotive,

Pick-me-up, or private-smile, by Jove is worth a fiver

A Colleen Bawn, a lady's blush, a cocktail, or a flash of lightning

Juleps, smashes, sangarees, or else a corpse reviver.’

The song climaxes with his consuming the lot.

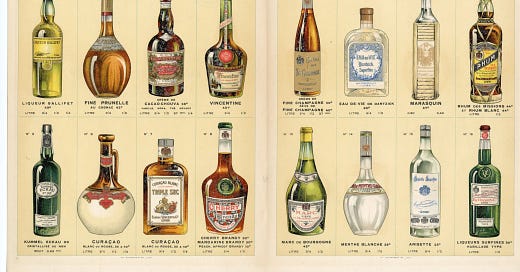

Setting aside such standard English terms as cocktail, julep and sangaree, spiced wine, diluted with water (ultimately Spain’s sangria) which in slang means not a drink but a drinking bout, these can mostly be ‘translated’, whether or not they were really available on this side of the Pond. The locomotive was a winter drink made of Burgundy, curaçao, egg yolks, honey and cloves all heated together; the stone fence or stone-wall was either whisky or some other spirit mixed with cider or ginger-beer and brandy (whether effect of the ‘wall’ was to stop you in your tracks, or perhaps to fall on you, is unresolved); a whiskey skin was any mixed drink that contained a large proportion of whisky. The rattlesnake presumably ‘bit’ the drinker (and had a ‘sting in its tail’) while the renovator and pick-me-up mimicked the corpse reviver.

A smile, fancy smile or private smile either promoted a smile through the sheer pleasure of its consumption or represented the ‘smile’ that was formed by lips open for drinking; it covered any drink, though whisky was the usual, and was found in do a smile, have a drink, and the invitation, will you try a smile? A smiler, logically, was a drinker, as well as a form of shandygaff, a mixture of beer and ginger beer or stout and lemonade. A flash of lightning (see below) began life in London as a glass of gin, but with its synonyms blue lightning, lightning juice, chain lightning and liquid lightning, for Americans it represented whisky or any form of cheap, strong liquor. Smash, from brandy-smash, was iced brandy and water.

Pink drinks, being seen as ‘girly’, attracted female names. Thus the lady’s or maiden’s blush (occasionally maiden’s prayers) which involved either port and lemonade or, in Australia, ginger beer and raspberry cordial. Australia added the barmaid’s blush which is ginger beer or rum plus raspberry cordial. It can also be a cocktail based on champagne or, again, the British favourite port and lemon. Unlisted, but contemporary, was flesh-and-blood, a loose approximation of the colours of the drinks, composed of equal measures of port and brandy

Last in the lyrics, Colleen Bawn. Slang knows no liquorous definition. The name, the anglicized version of Irish cailín bán, the white or fair woman, was used for the heroine of the opera ‘The Lily of Killarney’, first produced in 1862 at the Royal English Opera, Covent Garden, London. It was quickly adopted by rhyming slang and means a horn, an erection. This may suggest some sniggering link to cock-tail, but then again, perhaps not.

Still musical, and a century on, we meet spodiodi or bolly-olly, defined by Jack Keroac as ‘a shot of port wine, a shot of whiskey and a shot of port wine’, the sweet port playing the role of a ‘jacket’ for the whisky. The port tended to be cheap, and the whisky whatever generic version the bar was selling. The drink was much consumed by jazz musicians and beatniks and in 1949 inspired Stick McGhee’s song ‘Drinkin’ Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee.’ McGhee’s Wikipedia entry suggests that the original lyric ran ‘Drinkin’ wine motherfucker, drinkin’ wine!’

The young may lack finesse, but they know what they want. Obliteration. There are ways of achieving this, borne out in the names of the juvenile cocktails. Rocket fuel, a New Zealand mix which blends alcohol and a soft drink in a plastic bottle; the intent is presumably for the weak one to hide the strong. Snakebite began life as cheap but potent whisky and moved on to the modern mix of cider and lager, it can also mean a ‘cocktail’ of heroin and morphine. (The wider-ranging cider-and is any form of mixed drink in which the basic constituent is cider.) An anaconda is a mixture of strong beer and rough cider or scrumpy. Less in-your-face, even euphemistic, is the frat boys’ party juice, a cocktail of liquids including an unspecified alcohol content, typically served at fraternity parties.

Given the variety of ingredients, it is hard to isolate flavours, but a number of slang’s favourites must have been notably sweet. Thus the bishop, supposedly an episcopal delight, a mixture of wine and water, topped off by a roasted orange. Australia’s Madame Bishop combined port, sugar and nutmeg, but the suggested link to an Australian hotel-keeper is probably specious. Cherry-bounce, named for its effects, was either cherry brandy or brandy mixed with sugar; Poor Robin’s Alamanc, writing in 1740, suggested ‘Brandy, if you chuse to drink it raw / Mix sugar which it down will draw; / When men together these do flounce, /They call the liquor cherry-bounce.’

Blackjack was rum sweetened with molasses (as well as very strong black coffee, again plus molasses, or illegally distilled whisky.) The earliest blackjack, around 1600, was a vessel for liquor (either for holding it or from drinking from) which was made of waxed leather coated on its outside with tar or pitch.

Flip or phlip, both based on standard English flip, to whip up, was a mixture of beer and spirit sweetened with sugar into which one plunged a red-hot iron; hot tiger, an Oxford University speciality, mixed hot spiced ale and sherry (tiger’s milk, however is illicitly distilled whiskey). Humpty-dumpty was another hot drink (despite suggestion of falling, from walls or elsewhere, the name is based on the ‘humping together’ of the two liquors) made of ale and brandy boiled together. Bumbo, possibly based on Italian children’s bombo, drink, is brandy, sugar and water while rumbo, predictably, substitutes rum for the brandy. Still with brandy one finds hotpot, a hot drink made of ale and brandy, and conny wobble, eggs and brandy beaten up together. This cries out for an etymology but cony, a fool (nor standard English cony, a rabbit or that other slang use, a variation on cunny) hardly fits, while collywobbles, feelings of tension, fear or sickness, was coined a century later. Callibogus similarly demands a concrete origin, once again, this mix of rum and spruce beer defies the researcher.

Beer, already found in a number of mixtures, has other terms, mostly negative. Balderdash, long since used to mean nonsense, was once any adulterated or mixed drink, typically milk and beer, beer and wine, brandy and mineral water, which, while duly consumed, was generally considered unpleasant. All senses come from the 16th century balderdash, frothy water. The origin of this appears to be Scandinavian, whether in Danish balder, noise or clatter, Norwegian bjaldra, to speak indistinctly, or Icelandic. baldras, to make a clatter. The dash comes from Danish. daske, to slap or flap. The Welsh baldorddus, noisy, from baldordd, idle, noisy talk, chatter, may also play a role. An alternative etymology has been suggested (and backed up by a 16th century reference to ‘barbers balderdash’) as coming from the froth and foam made by barbers in dashing their balls (spherical pieces of soap) backwards and forwards in hot water.

Bilgewater is a straight steal from standard English bilgewater, the foul water that collects in a vessel’s bilges. For slang it means thin beer and beyond that any thin, tasteless drink, alcoholic or otherwise, although a mid-19th century example only denotes a mixed drink, not a weak one. Francis Grose offered three threads, ‘half common ale, mixed with stale and double beer’, it sounds unappetising. Three threads was often compared to porter (e.g. modern Guinness) and the 19th century’s bag of beer was a quart pot of beer, holding a mixture of porter and ale. Similarly black-and-tan mixed porter or stout with ale. Another lexicographer, Hotten has heavy wet and defines it as ‘malt liquor, because the more a man drinks of it, the heavier and more stupid he becomes’; it can also mean a heavy drinking bout, a mixture of porter and beer (also heavy cheer) and non-alcoholically, a downpour, a rainstorm.

____________________________

Whether the drinks that were produced during America’s 1920s temperance experiment, Prohibition, best remembered for its institutionalization of organized crime, strictly qualify as ‘mixed’ may be arguable. On the other hand, their constituents were rarely what they claimed, e.g. ‘whiskey’. So I offer a few. Bathtub hooch reflected the bathtub in which it was supposedly made (though it may also have tasted like dirty bathwater) and hooch, which had begin life as hoochinoo, an alcoholic liquor made by Alaskan Indians, especially the Hoochinoo people. Hooch survived prohibition: it can just mean liquor, even the good stuff, which at the time was known as the quill (from the pure quill, which had meant something flawless since the 1880s) or the real A.V., that is ante-Volstead: before Prohibition’s legal launch: the Volstead Act of 1920. Otherwise there was coffin varnish, alcohol’s equivalent to tobacco’s coffin nail, or monkey swill. A camouflage cocktail was any mix that might hide the poor quality liquor of the era. Or there was cougar juice which was part-adopted by US skiers’ in ‘Cougar Milk’, a blend of condensed milk, rum, nutmeg and boiling water; originally known as ‘moose milk’. Two-and-over suggests two shots and the drinker collapses; a ‘cousin’, perhaps, of block-and-fall, very strong and usually adulterated liquor sold, usually to African Americans in block and fall joints; ‘you’d got a shock, walk a block and fall in the gutter’ as Luc Sante has put it. At which point the local vultures stripped your pockets.

Prison, supposedly free of all intoxicants, is of course a veritable liquor store of home-brews. On the top shelf stands pruno, which suggests a one-time base of prunes, and which ‘classic prison drink’ is described thus in the prisoner’s dictionary, The Other Side of the Wall: (2000): ‘It is made by putting fruit juice, fruit, fruit peelings in a plastic bag with bread and/or sugar. The yeast in the bread along with the sugar helps ferment the fruit juice, fruit, or peelings. The plastic bag is usually placed down the toilet and secured so that it is not detected.’ Other prison creations include julep, the content of which are unlikely to be those in the term that originated it, the (mint) julep, ‘a mixture of brandy, whisky, or other spirit, with sugar and ice and some flavouring, usually mint.’ Other vegetable-based concoctions include spud juice (potatoes), silo, shinny and New Zealand’s hokonui.

___________

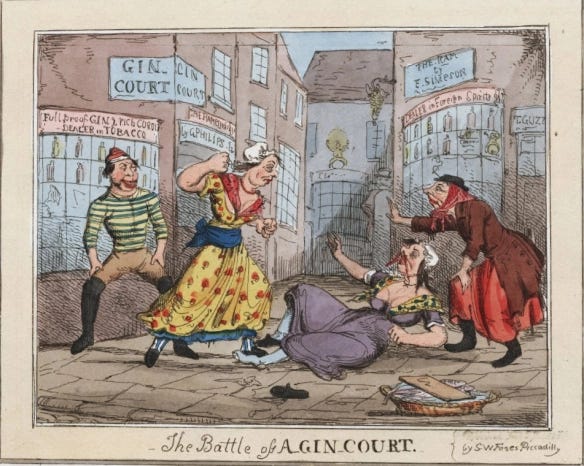

Slang’s shelves are weighed down with tempting bottles, but we can’t open them all. Reluctantly, we must pass over beer, whiskey and wine, but of all the major liquors, gin might be said to the most innately slangy. Like modern-day drugs, gin in its 18th century heyday was not just a drink, but a whole culture, closely knit to degeneracy, excess, poverty and the moral panics that such things tend to create. It was not simply mother’s ruin (a term that for all Hogarth’s celebrated picture of Gin Lane, is not recorded before 1917) but badged as the collapse of an entire society. Its drinkers were as addicted as junkies.

Queen Gin: Oh! what is is this that runs so cold about me?

A dram! — a dram! — a large one or I die.

’Tis vain [drinks hastily]

O, O, Farewell [dies]

Mob: What, dead drunk or dead in earnest?

Finale of The Deposing of Queen Gin,, with the Ruin of the Duke of Rum, Marquee de Nantz and the Lord Sugarcane, &c. by Jack Juniper

Those were the days, eh? Gin in parliament (with a much-reviled act which engendered those lines; nantz by the way being brandy, from Nantes), gin on stage, gin in ballads, gin in the press and of course gin in Hogarth’s Gin Lane – the one with the poxed drab, the falling baby, the skeletal lush, the collapsing house, the run-down pawnbrokers and similar snapshots of Merrie England. And gin wasn’t even gin. Not like what they mix with tonic at the cockers-p. or turns up in your over-priced ‘Shove-Me-Up-Against-the-Wall-Rip-My-Clothes-Off-and-Sod-That-You’re-Too-Pissed-to-Manage-It’ down Ayia Napa. No. Gin was genever, which was Dutch for juniper and thus en-slanged as Hollands or the Dutch drop or Geneva (even if that is in France) and a heavy drinker was taking his drops or reading Geneva print.

Nor was that all. far from it. It was Old Tom which memorialized Thomas Norris, who was employed at Hodges’ distillery and who opened a gin palace in Great Russell Street, Covent Garden. It was daffy, not because that was its effect (though it was) but from Daffy’s Elixir which was otherwise a proprietary remedy popularly merchandised as ‘the soothing syrup’. It could also be duffy, which also stood for a quarter pint measure, or it was deady, again nodding to its effects, but this time from a distiller, one D. Deady of Sol’s Row off Tottenham Court Road. Tom and Jerry, in Life in London, went East to debauch at All Max, which not only punned on the West End’s fashionable Almacks but played with max or old max, which meant gin. A max-ken sold the stuff and the drunken clientele were maxy. Across the Pond the modern Tom and Jerry is a Christmas favourite, a highly spiced hot punch, basically a variant of eggnog with brandy and rum added and served hot. But there is no gin.

It was transparent; it came in colours: blue or white; some saw it as a form of textile. The first led to brilliant, which was raw and undiluted (raw was another name), and clear crystal and thence strikefire, flash or strike of lightning or thunder and lightning (which added bitters). This last atmospheric blend also translated as a mixture of shrub (any spirit – usually rum – mixed with orange or lemon juice) and whisky; a later, innocuous definition refers to treacle and clotted cream, while by 1900 it smacked of Yuletide clichés, being simply flaming brandy sauce.

Transparency gave see-through which moved on to whiteness, and asking for white port or white wine in the wrong tavern might not get what you expected. The ‘port’ and ‘wine’ were meant to be euphemisms, so was the later twankay or twankey which in tea trade jargon meant green tea and might be the origin of the pantomime dame Widow Twankey. Bunter’s tea referred to the bunter, a run-down old whore or a female rag-scavenger. Prohibition speakeasies, though probably through coincidence, were known to serve their varieties of rotgut in teacups.

It could be true blue or light blue and a century on bluestone which in standard English means copper sulphate or even sulphuric acid. The textiles suggested smoothness and were coloured as well: blue or white ribbin, i.e. ribbon, which played on the earlier blue or white tape (which might have been underpinned by taphouse) which could also be red tape (though ‘red’ in drinks was usually brandy), and white velvet or satin (later appropriated by the distiller Sir Robert Burnett in 1770). A yard of satin or of tape was a glassful. The main blue was blue ruin, one of mother’s first recorded ‘little helpers’ and thus her ruin too, though another synonym was mother’s milk, as were cold cream and cream of the valley.

Less appealing was rag water, so called as Captain Grose explained because ‘these [are] liquors seldom failing to reduce those that drink them to rags.’ Not that one might always boast even a rag: stark- or staff-naked suggested raw alcohol, ‘unclothed’ in congeners or mixers, not to mention the poverty of its drinkers. Strip-me-down naked was synonymous. Some saw it as an universal panacea: meat-drink-washing-and-lodging.

The effects provide a regular flow of imagery: busthead, crank (which ‘mixed gin with water and ‘cranked you up’), kick in the guts, roll-me-in-the-kennel (a kennel being a gutter), gunpowder (your head ‘went off with a bang’), heartsease, kill-grief (but also kill-cobbler which suggests a professional propensity), tittery, which in dialect meant tottering along on the verge of collapse, and wind which ‘caught your breath’. Diddle was another one that meant unsteadiness, and the diddle-cove or –spinner was the landlord of a diddle-ken. Then there was the simply uncompromising: ruin, misery or poverty, though royal poverty suggested that at least for a while you would ‘feel like a king’. Much later came South Africa’s Queen’s tears, a Zulu term back-referring to the tears Queen Victoria supposedly shed after her troops’ defeat at Isandhlwana in 1879.

As in the martini (not to mention the camp if defunct English martini wherein tea is mixed with gin), gin works as an ingredient. There’s the dog’s nose (like the animal’s nose, the drink is black): beer warmed nearly to boiling, sugar, ginger and gin or wormwood (the basis of absinthe); absent wormwood, substitute brandy. It also referred to an alcoholic whose preferred tipple is whisky. Another gin-and-wormwood combo was purl (possibly linked to standard purl, a rill or whirl of water) which used the dog’s nose ingredients plus sugar and ginger. It was a popular morning pick-me-up and a cut-down version, early purl simply heated beer with gin. So popular was the combination that there were purl-shops, specialising in the drink, which were run by purl-men. There was also the purl-royal, a glass of Canary wine with a dash of wormwood.

Gin and beer could also be huckle-my-buff or –butt which uses dialect’s huckle, to jog along, thus making it literally ‘jog my skin’ or ‘my buttocks’. Sometimes eggs and brandy were included (though the gin was then left out.) Ultimately it crossed the Atlantic where it is bourbon and milk poured over crushed ice, and recommended as a hangover cure. Piss quick – either from its resemblance to urine or its possible micturative effects – is gin mixed with marmalade topped up with boiling water. Twist seems either disgusting – a mix of tea and coffee – or a guarantee of a hangover: it could mean any mixed alcoholic drink, typically brandy and eggs or brandy, beer and eggs, brandy and gin or, as a gin twist, gin and hot water.

Ever-popular was hot, sometimes hot with, described by George Parker in his London guide Life’s Painter of Variegated Characters in Public and Private Life (1789) as ‘a mixed kind of liquor, of beer and gin, with egg, sugar and nutmeg.’ He added that it was ‘drank mostly in night-houses, but when drank in a morning, it is called flannel.’ Like the material flannel ‘kept you warm’ and if you were wrapt in warm flannel you’d had too much. It was still being drunk, at least in Australia, before World War I. An older name, which underpinned flannel, had been lambswool.

And for the really desperate, there was alls, which came either from all nations, as in ‘flags of…’, or more basically ‘all the leftovers’. (Up the market Victorian wine merchants talked of omnes, the odds and ends of various wines). Either way it consisted of the dregs collected from the overflow from the pouring taps, the ends of spirit bottles and similar leavings; it was sold cheap in gin shops where female customers, misogynists claimed, were particular devotees.

A cocktail composed of gin and ice, with a little sugar and a trace of water was a monkey-chaser; a steel bottom (perhaps from the need for such a lining to one’s stomach to drink such a thing) was comprised of gin and wine; mahogany, from the colour, blended either gin and treacle or brandy and water; finally bitter-gatter mixed beer (from Romani gatter, water) and gin

By 1736 the gin craze, boosted by unlicensed production and heavy duties on imported spirits, proved too much: Parliament passed the Gin Act, adding high taxes to what had been a poor man’s tipple. The drinkers rioted. The tax was removed in 1742 but the spirit was in decline. Further legislation in 1751, which limited sales, was a law too far.

‘Ye link and shoe boys clubb a tear,

Ye basket-women join;

Grubb-street, pour forth a stream of brine,

Ye porters hang your heads and pine;

All, all are damn’d to rot-gut beer.’

Timothy Scrub ‘Desolation, or, The Fall of Gin’ 1736

_________________________________

Now for something not really all that different. The tone is lowered, refinement a far-off chimera. Let us talk slang’s tipple of choice, the blue, the blushful cru argotois, let us talk meths.

O for a beaker full of the warm South,

Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene,

With beaded bubbles winking at the brim.

And purple-stainèd mouth;

That I might drink, and leave the world unseen.

Keats’ ‘Ode to Nightingale’. Seemingly irrelevant but the poet got two things spot-on: the geography and, or nearly, the colour. Because while the chilly north, i.e. the UK, seems reticent in its naming of this ethanol/methanol mix, the warm and Southern lands of Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, are far more creative. And denatured alcohol, its official name, is very often purple, or at least a variety of muted violet.

Australasia’s contribution is marked upon its own map. There is bush champagne, defined as a pannikin of methylated spirits mixed with river water and a spoonful of sal volatile (the latter being better known as smelling salts). An alternative is the similarly constituted Northern Territory champagne. The salts give it that larky fizz. There is bidgee, from the Murrumbidgee River, and presumably those drunkards who frequent its banks, and the urban Fitzroy cocktail, celebrating a suburb of Melbourne. Decant methylated spirits as preferred, and add some form of mixer to mediate the taste. Meths could also be round the world for a dollar, with alternative sums listed as threepence, fourpence or ninepence. In all cases the ‘trip’ was provoked by meths, or a very cheap but almost equally potent wine.

Other terms from the lucky country have included Jessie’s Dream and Johnny Gee. Jesse is lost to etymologists but generic Johnny is seen as ‘gee-ing up’ the drinker. So too does jumpabout. Then there has been fix bayonets, a New Zealand term from World War I, a meths and orange mix used as a form of Dutch courage; lunatic soup or broth (which also denotes cheap red wine); World War II’s fong or fong-eye, underpinned perhaps by Australia’s on-going terror of the so-called Yellow Peril. Goom is attributed to the Jagara language of Queensland, in which goom, less intoxicatingly, means simply water; bombo, which can be meths or cheap wine or a combination of the two, ‘knocks one out’. Atom-bombo simply punned on the drink and the recently empowered weapon. The white lady, otherwise a cocktail composed of two parts of dry gin, one of orange liqueur and one of lemon juice, can also, context permitting, be plain meths as well. Steam is another meths-and-wine cocktail, while steamboats rejects the wine and adds tea – Chinese, Indian or even Australia’s own post-and-rail –to the ethanol base.

South Africa’s standout term is vlam, from the Afrikaans for flame, but there are a variety of others: ai-ai (a mispronunciation of ‘A.A.’ or absolute alcohol), queer stuff, mix, fly machine (presumably from the effect of the drink ) and speed trap. The meths drinker is a spiritsuiper, literally a ‘spirit swiller’. But if these are relatively few, the country makes up with its accentuation of colour.

There is bloutrein (sometimes Englished as blue train), a dubious tribute to the Blue Train, a luxury passenger train running between Cape Town and Pretoria; those who drink meths are seen as boarding the ‘fast train’ to death. Slower but considered equally sure is blouperd, using Afrikaans perd, a horse. There is blue ocean and die blou, i.e. the blue. There is also, from New Zealand, the blue lady and from Australia pink-eye.

There is of course the simple meths itself, otherwise meth (not to be confused with über-speed methedrine) and metha. There is Ireland’s blow or blowhard, and chat, all apparently from the garrulousness that meths drinking can promote. Feke, meaning fake, and thus representing ‘fake alcohol’, was a favourite of the Thirties; drinkers usually added it to beer. If the meths was diluted with water it was known as milk, since the pure alcohol became cloudy.

America’s best known synonym is canned heat, or the proprietary Sterno (as in the original ‘Sterno-Inferno’ alcohol burner); its drinkers were the canned heater and canned-heat stiff. Jack is another US term and has been extended to cover a variety of illicitly distilled liquors, e.g. tater jack (potatoes), prune jack and raisin jack. There is also jake, which doubled as Jamaica ginger, an alcoholic but still legal high much favoured during Prohibition. The legs of habitual consumers became paralysed, leaving them jakelegged. Finally, fittingly, there is finish. Which, so it would appear, does to the drinker exactly what it promises on the label.

But is that really the end? Perhaps not. One drinks, imply so many of these names, to get drunk. Not so simple. The morning-after-the-night-before demands its due. We’ve noted the corpse-reviver. The eye-opener, that first drink of the day, is seen as similarly helpful. Suitably, the doctor is a morning hangover cure. A convenient term, its other meanings have included a drink of milk and water with rum and nutmeg, brown sherry, and alum, or any other form of adulterant, used to dilute food or drink. Thus a publican who sold bad liquors is said to keep the doctor in his cellars. The black doctor, full-strength Coca-Cola, apparently prescribed as required. If all else fails, there’s always the hair of the dog: it’s been a very good boy since at least 1546.

L’chaim!