[It is not many countries (to my knowledge it is not any other at all) wherein the first of the nation’s dictionaries, large or small, was one of criminal slang. Thus, however, it was in Australia. In fairness, around the time of writing, 1812 or so, there wasn’t a great deal of speech that wasn’t coming from criminals (the lags or transportees who in 1788 had started arriving in what the UK saw as a convenient penal colony now the US had become irritatingly independent). Or if not crims then their warders or the soldiers, far keener on running the lucrative rum trade than a load of problematic villains with nothing much to do bar polishing the king’s iron with their eyebrows.

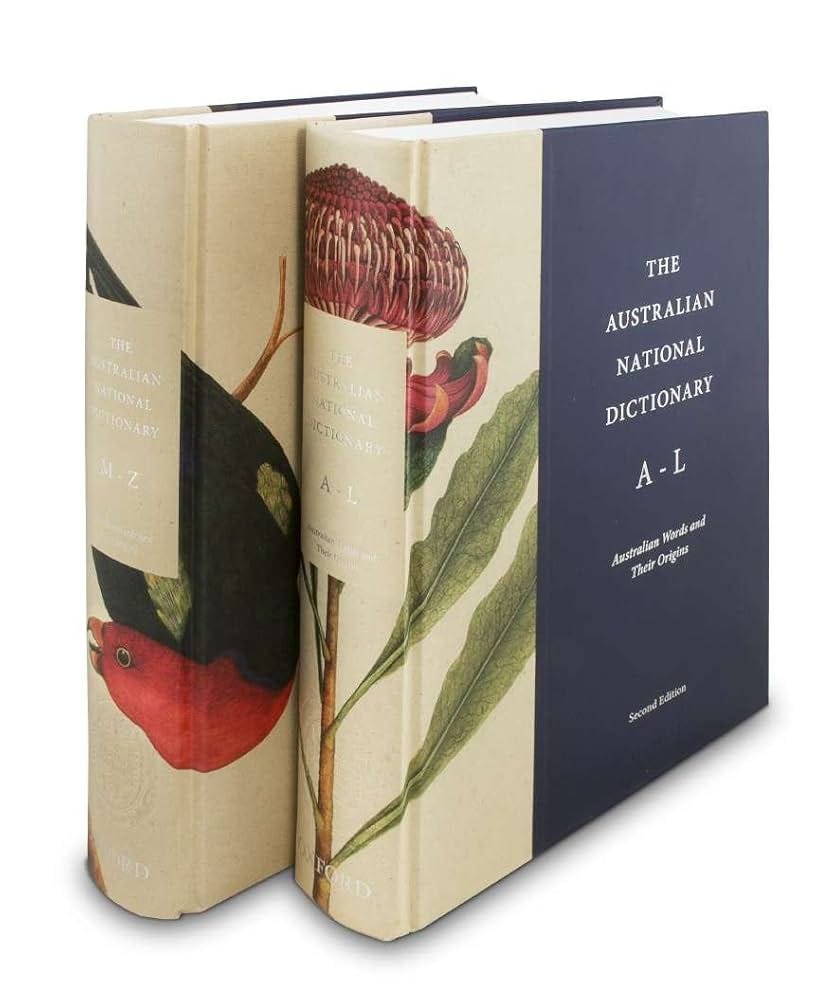

I approached the story of Australian slang lexicography in my history of the craft, Language! in 2014. Now, with the flimsy but ever-advocated justification of economic tightening, it seems that the Australian National Dictionary, home to all forms of Antipodean coinage and certainly not merely slang, and acknowledged as the jewel in Godzone’s lexical crown, is facing the chop. The literate end of bogan-world is no longer cashed up, the mazuma is no longer on offer for running the lexicon, now working on a third edition, and all the pleas (mine included) in favour of continuing with so vital a resource, are getting the arse.

I don’t imagine that what follows will help mitigate this undeniable tragedy, but for what it may be worth I offer Language’s take on Australia’s first dictionary-maker and the nation-building dictionary he made more than two centuries past]

__________________________

’Tis the everyday Australian

Has a language of his own,

Has a language, or a slanguage,

Which can simply stand alone.

And a ‘dickon pitch to kid us’

Is a synonym for ‘lie’,

And to ‘nark it’ means to stop it,

And to ‘nit it’ means to fly.

And a bosom friend's a ‘cobber,’

And a horse a ‘prad’ or ‘moke,’

While a casual acquaintance

Is a ‘joker’ or a ‘bloke.’

And his lady-love's his ‘donah’

or his ‘clinah’ or his ‘tart’

Or his ‘little bit o' muslin,’

As it used to be his ‘bart.’

W.T. Goodge ‘The Great Australian Slanguage’ in The Bulletin 4 June 1898

The ‘First Fleet’ captained by Arthur Philip and bringing with it in its 11 vessels some 148 male and 188 female convicts, all sentenced to transportation from England to New South Wales (‘discovered’ by James Cook in 1770), made landfall in Botany Bay on 20 January 1788 and arrived in Port Jackson, modern Sydney Harbour, six days later. It was the first such convoy to bring British criminals to Australian shores — transportation to America having ceased in 1776 a substitute had urgently to be found; its successors would continue coming until the 1840s and the system would not be wholly abandoned until 1868. Some 165,000 prisoners would arrive to fill the penal settlements. They were not alone: an increasing flow of free settlers would join them: in 1852 alone, drawn by the contemporary gold rush, 370,000 would make the journey and by 1871 Australia’s population had reached 1.7 million. By 1900 there were around 3,788,000 Australians and the current statistics show just over 22.5 million. It remains a country that draws in immigrants: figures for 2010 show that judged by ‘country of birth’ former citizens of some fifty nations chose in that year to start new lives ‘Down Under’.

James Hardy Vaux arrived in New South Wales in 1801. He was 19 and about to serve the mandatory minimum term of 7 years judicial exile. He had been born in Surrey, the son of a butler and a house steward, had been apprenticed to a linen-draper in Liverpool and then fallen amongst the necessary ‘bad company’ that gave him a taste for cock-fighting, and thus gambling and thence launched him on his criminal career. Moving to London, living on his wits and rarely employed for long, Vaux was not violent, but ran the gamut of petty crimes, with a lucrative sideline in peddling plausible sob-stories in return for his victims’ charitable donations. He survived unscathed, despite an arrest for pilfering, but in 1801, convicted of stealing a handkerchief, was charged, tried and sent to what was still a relatively new-formed colony.

Here Vaux was lucky: rather than labour, and thanks to penmanship skills that he regularly employed in forgery, he was employed as a clerk and in 1807 was able to sail back to England. Here he returned promptly to criminal form, and ‘exercised alternately the following modes of depredation […] buzzing, dragging, sneaking, hoisting, pinching, smashing, jumping, spanking, starring, the kid-rig, the letter-racket, the order-racket, [and] the snuff-racket.’ It is in character with The Memoirs’ invariably self-serving style that he adds that ‘considering our youth and inexperience, [we] evinced a good deal of dexterity’. He also, ‘least the reader be unprovided with a cant dictionary’[1], explains them all.

Not enough dexterity, it seems. Predictably he was re-arrested and as a second offender, now facing the more serious charge of stealing jewellery, was sentenced to transportation for life. He returned to New South Wales in 1810. A year later he was sentenced again, this time for receiving stolen property, possibly via a servant of the suitably named Judge Bent, and sent to Newcastle, known as a ‘place of secondary punishment’ and a hard-labour prison within the country’s greater one. This ‘hamlet of punishment’, as Robert Hughes has termed it, was designed to make incorrigible criminals suffer. ‘Everything seemed either exhausting or boring, but that was what commended it to the authorities.’[2] Yet again Vaux seemed to have been lucky. Rather than logging in the fast diminishing cedar forests, or suffering in the mines or at burning lime – and despite an abortive escape attempt for which he received 50 lashes – he managed to obtain another clerking job.

Writing in 1792, in A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, Watkin Tench, a young officer of marines who had volunteered for a posting in Botany Bay and had sailed in the First Fleet, had noted: ‘A leading distinction, which marked the convicts on their outset in the colony, was a use of what is called the “flash”, or “kiddy” language. In some of our early courts of justice an interpreter was frequently necessary to translate the deposition of the witness and the defence of the prisoner. This language has many dialects. The sly dexterity of the pickpocket, the brutal ferocity of the footpad, the more elevated career of the highwayman and the deadly purpose of the midnight ruffian is each strictly appropriate in the terms which distinguish and characterize it. I have ever been of opinion that an abolition of this unnatural jargon would open the path to reformation. And my observations on these people have constantly instructed me that indulgence in this infatuating cant is more deeply associated with depravity and continuance in vice than is generally supposed. I recollect hardly one instance of a return to honest pursuits, and habits of industry, where this miserable perversion of our noblest and peculiar faculty was not previously conquered.’

The equation of slang with vice was nothing new. Vaux, no doubt unconsciously, took up where Tench had indicated. Though not with plans for abolition of the ‘flash’ language, but for its explication. It was during his time in Newcastle, ‘during his solitary hours of cessation from hard labour’, that Vaux produced what continues to be credited as the first dictionary of any kind with reference to the Australian language: A New and Comprehensive Vocabulary of the Flash Language. The preface, dedicated to the then governor of Newcastle, Thomas Skottowe, is dated 5 July 1812. ‘I trust the Vocabulary will afford you some amusement from its novelty,’ said Vaux, ‘and that from the correctness of its definitions, you may occasionally find it useful in your magisterial capacity.’ The Vocabulary did not appear in print, however, until 1819, when it appears as an addendum to Vaux’s unashamedly picaresque Memoirs, published in London by John Murray.

Although Julie Coleman has suggested that life in the Newcastle camp would have been too tough to allow for writing,[3] and opts to date the Vocabulary alongside the later Memoirs the dedication to Skottowe (replaced as governor before 1819) and more importantly the terms included suggest the earlier date. Noel McLachlan, who edited both works in 1964, has no problem dating them separately. And Prof. Coleman herself, who provides a detailed breakdown of Vaux’ 332 entries, notes that one third of the entries could be found in either Humphrey Potter’s New Dictionary of the Cant and Flash Languages of 1790 or the Lexicon Balatronicum of 1811. (However, as she notes, this does not prove that Vaux had actually consulted either work.) To what extent the moonlighting clerk drew on his personal experience of the criminal world – which was undoubtedly wide enough – or on ‘field-work’ among his fellow-transportees is unprovable. But while his work is credited as the first dictionary of any kind to have been published in Australia, it cannot be seen as dictionary of homegrown Australian language. It is, rather, a somewhat abbreviated selection of what was available in the late 18th and early 19th century London underworld.

One can also assume that in common with the readers of most canting dictionaries, those who obtained copies of Vaux were not those whose jargon filled its pages. Amanda Laugesen, in an essay in the Australian Dictionary Centre’s newsletter Ozwords on ‘Botany Bay Argot’[4], has suggested that Vaux’s glossary was as much a reflection of the continuing British upper-class fascination with the criminal world and its language – thus Tench’s observations – as it was a record of actual convict speech as found in the penal settlements. Vaux was hardly an aristocrat, but he was writing at least in part to inform a member of the authorities. Indeed he seems to have made no attempt to publish the Vocabulary until it was appended to the Memoirs in 1819. Tench had mentioned the need for an interpreter, and twenty years on, Vaux put himself forward to Governor Skottowe as a lexical aide.

He was not, however, making it up. Whether or not it was current in New South Wales, this was an established vocabulary used by a recognised group. That terms such as charley ‘a watchman’; pall ‘a partner, companion, associate, or accomplice’; stick ‘a pistol’, crib ‘to die’ or such terms for money as bean, bender, bob, coach-wheel, crook, rag and quid made their way across the seas was hardly surprising. No more so burick, judy or mot for whore, or adjectives such as cross, criminal or untrustworthy and its antonym square, or flash, pertaining to the underworld. These were all terms prisoners would have known and continued to use. In addition Vaux offers certain terms that came directly from the convict experience. For instance bellowser, originally a prize-fighting term for a blow to the stomach, but now a sentence to transportation: both ‘take one’s breath away’. Similar is nap a winder, to be transported; a winder also deprived one of breath, but as with bellowser, there is also the image of the wind in the prison ship’s sails. The word lag was not coined in Australia (it is recorded in 1760 with reference to America) but became identified with its penal settlements. Vaux has lag as ‘a convict under sentence of transportation’ and is first to record the old lag, ‘a man or woman who has been transported, and is so called on returning home’. The term would go on to mean any veteran prisoner, incarcerated or (currently) free, and be used in the UK as often as in Australia. The verb would come to refer to any form of imprisonment, and is found as such in 1840s Australia. He also has lag ship, ‘a transport chartered by Government for the conveyance of convicts to New South Wales; also, a hulk, or floating prison, in which, ‘to the disgrace of humanity, many hundreds of these unhappy persons are confined, and suffer every complication of human misery.’[5] Vaux’s second voyage out had been prefaced by a period in the hulks: he knew of what he wrote.

Where Vaux does note and demonstrate that language was altering (and thus defies the belief of some negative critics, that his was merely a pseudonym for some London hack) was in his appreciation of the way in which certain terms, while already common in London, had undergone a change in their new environment. These were nowhere as radical as the renaming of flora and fauna that provided much new and truly ‘Australian language’ but they showed the way words, like people, were in transition. The emblematic example being swag. Swag had meant criminal booty since the mid-18th century; prior to that it had first been used as a shop (and its stealable contents) and then to mean money. Vaux has that sense (‘The swag, is a term used in speaking of any booty you have lately obtained, be it of what kind it may, except money, as Where did you lumber the swag? that, is, where did you deposit the stolen property? To carry the swag is to be the bearer of the stolen goods to a place of safety’[6]) but he also offers, as his first definition, ‘a bundle, parcel, or package; as a swag of snow’ [i.e. linen or washing]. It was this swag, denoting the pack carried by an itinerant, that would, with such derivatives as swaggie, swagger, and swagman, become Australia’s primary use.

Vaux made some £33 from his memoirs (half the profits). His career is unknown after the publication but he absconded from New South Wales sometime before 1830 and made his way to Dublin. Arrested again he was transported, for an unprecedented third time. Nothing more is recorded, other than a brief court appearance, and it is assumed he died in Australia.

The Vocabulary did not appear in the second, 1827 edition of the Memoirs, but Vaux, at least as a character, did appear in William Moncrieff’s ‘serio-comical, operatical, melodramatical, pantomimical, characteristical, satirical, Tasmanian, Australian extravaganza’ Van Diemen’s Land! or Settlers and Natives, which played London’s Surrey Theatre in early 1830. The fictional Vaux leads his fellow-convicts in the egalitarian verse, ‘Ne'er droop brother convicts, but keep up the ball, / For in court, or in cottage, in hovel or hall, / Mankind, as occasion permits, are rogues all, / Sing Tantarantara, rogues all, &c.’, delivers a couple of speeches and joins the ‘convict galopade’ that concludes the scene.

[1] Vaux Memoirs (London 1819) I pp. 144-5

[2] R. Hughes Fatal Shore (London 1987) pp. 425, 435

[3] Coleman op. cit. p. 141

[4] andc.anu.edu.au/ozwords/Nov%202002/Botany%20Bay.html

[5] Vaux op.cit. II p. 185

[6] Vaux op.cit. II p. 216

I'm doing my bit to help:

https://languagehat.com/australias-national-dictionary-under-threat/

Me too. But I wish I were feeling more confident that sense will prevail.