Nantee dinarly [‘no money’], the omee of the carsey [‘landlord’]

Says due bionc peroney [‘two shillings apiece’], manjaree on the cross [‘food for free’].

We’ll all have to scarper the letty [‘leave the’ ‘lodgings’] in the morning,

Before the bonee omee of the carsey [‘landlord’, lit. ‘good man of the house’] shakes his doss [‘gets up’, lit. ‘shakes out his bed’].

A Popular Busker Song, ‘in 6/8 time to a guitar accompaniment’

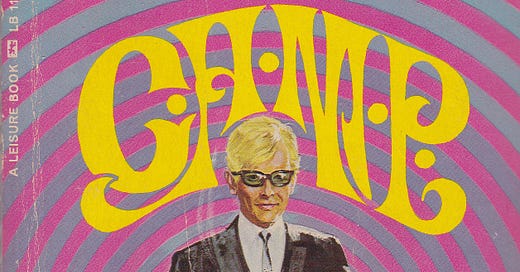

[I wrote a chapter of Language! my 2014 history of slang on ‘gayspeak’ (a term coined in 1981 in J.W. Chesebro’s study Gayspeak: Gay Male and Lesbian Communication). This section on Polari, which developed a piece first researched for an academic journal some years earlier, was included. It ends with a valediction: Polari had come, had flourished, but now it had gone for good. Once a genuinely necessary secret language, it was no longer wanted on homosexuality’s voyage. The publication earlier this year of Richard Milward’s novel Man-eating Typewriter, written almost wholly in Polari, has not reversed that verdict, but the book is worth at least some modification of the original text. It is, without argument, a tour de force.]

No overview of the homosexual lexis can ignore an important sub-set: polari, originally lingua franca. ‘Lingua Franca’, in the original Italian, means literally ‘the language of the Franks’, i.e. French, and was born as a form of hybrid tongue, based on Occitan and Italian and used in the Mediterranean for trading and military purposes. From there it spread, and it is possibly this ‘French tongue’ (also known as ‘Pedlar’s French’) that Chaucer has in mind when he teases the Prioress for speaking the ‘French’ of Stratforde-atte-Bow’ - since ‘Frensh of Paris was to hir unknowe’. (That said, the reference may be to the generally ‘provincial’ character of the French spoken in England - heavily influenced by the Norman dialect). Today’s use of ‘Lingua Franca’ tends to sustain this image of a trader’s pidgin, referring inter alia to Tok Pisin in Papua New Guinea or Krio in Sierra Leone, but in 17th century Britain it began to gain an alternative role: a synonym for the language, properly a jargon or ‘professional slang’, used (among other vocabularies) by tramps, sailors, show people and (somewhat later) homosexuals. In this role it gained a new name, variously spelt parlyaree, palarie and, for the purposes of this discussion, polari (suggested by some to be a strictly gay use of the term, but in fact one more spelling of a term that originated in the standard Italian parlare, to speak.)

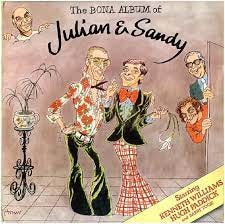

Quite how a trade pidgin came to form the basis of a language first (and last) heard by most Britons via the ostentatiously ‘camp’ cross-talk of ‘Julian’ and ‘Sandy’ (Hugh Paddick and Kenneth Williams), an unashamedly queeny duo - ‘great bulging thews and wopping great lallies’ - created for BBC Radio’s ‘Round the Horne’ and ‘Beyond Our Ken’, staples of the 1960s airwaves, needs some explanation. (One script even referenced ‘Polari’ but few would have understood what it might be.) Jules and Sand were not the only popular Polari speakers. The late Sixties drag artist Lee Sutton scored a hit with ‘Bona Eek’, explained by Paul Baker: ‘His pièce de resistance (that’s your actual French), was “Bona Eek”, an increasingly cruel parody of “Baby Face”. Sutton gave a translation of the song in its second half, but purposefully misled the audience for further comic effect.’)

As far as show business is concerned, the link, as generally accepted, is that of the sea. It would seem that sailors, who naturally picked up ‘Lingua Franca’ on their trips abroad, brought it home and thence to their on-shore jobs: typically working as pedlars, and joining travelling fairs and circuses. The link between sailors and the stage was certainly established by the 19th century, and can still be seen in a variety of backstage terminology; jack tar, with his skills at climbing to precarious heights, was much in demand. Not for nothing are such terms as ‘rigging’ and ‘flying’ common to both professions. More general, and typical of the geographical/occupational progression is a term like palaver, to chatter, to gossip and thence, as a noun, a noisy fuss. Ultimately taken from the Portuguese palabra, speech, or talk, the term was used by Portuguese traders on West Coast of Africa, where it was picked up by British sailors, incorporated into their jargon and thence rendered part of the Polari used on the mainland. From there, as with a number of slang or jargon terms, polari or otherwise, it made its way into colloquial English.

The link to homosexual use, which, at least as recorded, emerges a good deal later than that with show business, forces one into the realm of stereotyping. The automatic union of the stage and homosexuality, and likewise of sailors (‘rum, sodomy and the lash’) and the gay world is cliched, politically no doubt far from correct, but unavoidable. Where the two groups overlap is an opaque area - seaboard privations are the obvious point - and Kellow Chesney, in his Victorian Underworld (1970, and itself largely a distillation of Henry Mayhew’s London Labour & the London Poor, 1851) suggests that the great centres of male prostitution were the nation’s ports. But above all it would seem that the pre-Gay Liberation male homosexual world, like any ‘secret’ sub-group of society, both required and desired some form of ‘secret’ language, working simultaneously to affirm the secret unity of the outcast, and by ‘speaking in tongues’ to hide from the larger, hostile world. Polari, whether picked up from sea-faring pals, or adopted from the world of the theatre, fitted the bill. Gay slang existed, but, drawn on languages other than standard English, Polari was even less accessible. It was not generated by the gay world, but came top-down as it were, a ready-made ‘lingo’, to use a suitably Polari term. It is, as noted, a male preserve. Given, presumably, that lesbians existed only as a ‘virtual’ entity in the 19th century, they could hardly be accorded a vocabulary. More recently it has been suggested (in a Channel 4 documentary in 1993) that contemporary London lesbians have picked up a number of terms, but the evidence is thin. Polari, in its prime, was (real) boys’ only.

Despite the relative cohesion that the verse quoted above suggests, Polari has never really been a ‘proper’ language. Unlike such constructs, it had no grammar or syntax of its own, and relied without difficulty on recognised English forms. It was not a ‘foreign’ language in any sense. Instead, as the American academic Ian Hancock has noted, Polari was, even at its peak, at best a lexicon, a vocabulary list of discrete words (and a few phrases). Quite how many there were is unknown, but current lists, gathered irrespective of context (i.e. circus, theatre or homosexual) count barely more than one hundred in all. But its individual words and phrases could be used with ease to formulate sentences, paragraphs and, in this case, rhymes. In that it resembles slang, or more so cant, from which an early collector such as Thomas Harman could similarly construct passages - supposedly chats between 16th century villains - top-heavy with the closed vocabulary of the professional malefactor.

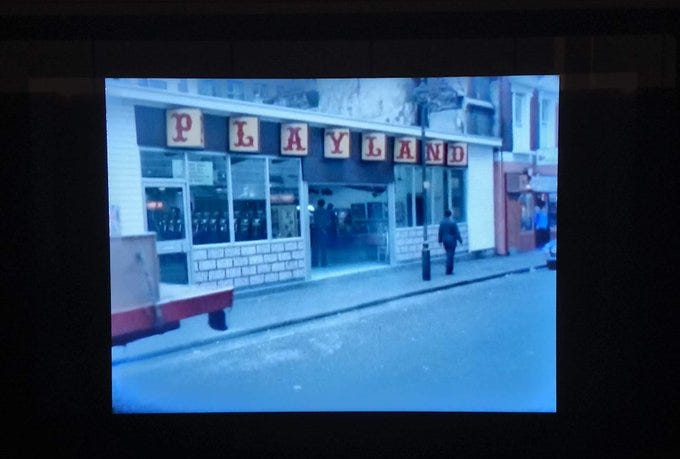

That the show business end of Polari has gradually declined is probably no surprise. The show business that spawned, or at least popularised it, has declined too. The vocabulary of TV and movies is harder-edged, more overtly technical. The provincial rep tour may still struggle on, but few thesps would imagine calling their landlord a ‘bona omee of the carsey’ (and the Londoners would wonder quite where the lavatory, another definition of carsey albeit sharing an etymology, fitted in). Its decline within gay circles offers another story, one that is linked to changes in gay speech in general. Polari was never the sole repository of gay conversation. Standard English aside, there was ‘gayspeak’, a language that encompasses polari and the camp enunciations (flourishing from the 1940s-60s) of what can be seen as a ‘queen culture’, where ‘Your mother’ meant ‘I’, ‘Lily’ was an all-purpose prefix, e.g. ‘Lily Law’: the police or the ‘Lilypond’, the nickname of the popular 1930s cruising cafe the Lyons Corner House in Coventry Street, London. ‘Queen’ itself appeared in a myriad of combinations: ‘dinge queen’: one who liked black lovers, ‘pine-apple queen’: an aficionado of Hawaiians, and ‘kaka queen’: a coprophile. They were often plucked wholesale from America, where ‘Mary’ as a term of address, was especially popular. They had been classified as girls, and ‘girls’ they would be, in spades.

The emergence of Gay Liberation in the late 1960s put paid to all that. Queen culture was too self-effacing, too meek, too hole-in-the-corner for the new self-assertiveness. ‘Clone culture’, which replaced it in the 1970s, with its in-your-face macho imagery, rejected Polari wholesale. There would no longer be a place for this artificial narrative, as concocted for Gay News:

‘As feely homies [‘young men’], when we launched ourselves on the gay scene, Polari was all the rage. We would zhoosh [‘fix’] our riahs [‘hair’], powder our eeks [‘faces’], climb into our bona [‘nice’] new drag [‘clothes’], don our batts [‘shoes’] and troll off [‘cruise’] to some bona bijou [‘nice, small’] bar. In the bar, we would stand around parlyaring [‘chatting’] with our sisters [‘gay acquaintances’], varda [‘look at’] the bona cartes [‘nice genitals’] on the butch homie [‘masculine male’] ajax [‘nearby’] who, if we fluttered our ogleriahs [‘eyelashes’], might just troll over [‘wander over’] to offer a light.’ [1]

What counted in the new ‘out’ world were ‘buns’ and ‘pecs’, not ‘riah’ and ‘lallies’ (‘legs’). For a veteran merchant seaman, emerging into London gay life in 1985 after fifteen years away, ‘that was difficult. ‘[I’d been in] that world of the Fifties and Sixties, and it had been a very insular, self-contained life.’ [2] For his younger peers, it was no more than kow-towing to ‘the value-system of a racist patriarchal culture...[its users] engaging in self-oppression’. [3] Using any form of camp language, however useful it might have been to a sub-culture which accepted, even if reluctantly, the oppression it faced, was simply affirming the justice of that oppression. It was another facet of the closet, and it had to go.

Today, given the use of the once outlawed ‘queer’ to turn the (ironic) tables on the homophobes in the same way as young Black boys, esp. in the ‘gangsta’ environment, describe themselves as ‘niggers’, it has been suggested that Polari could stage an equally ironic revival. ‘Omi-palone’, the ur-term, literally ‘man-woman’ and thus homosexual (with all the stereotyped baggage the term implies) could be revived in pride rather than abandoned in shame and disdain. Nor have the queens vanished. Contemporary America has ‘green queen’: one who looks for sex in public parks, while ‘drama queen’ has joined mainstream slang in meaning a hysteric irrespective of sexuality. [4] But Polari, if not dead, is in its final throes. A few terms like fab (from ‘fabulosa’), charva (to fuck) and camp itself have survived as refugees in the mainstream. The rest have gone, longterm prisoners in the slang dictionaries, labelled ‘obs.’ for obsolete. [5]

_____________

At which point slang, ever mocking, ever subversive, tells me: not so fast, aged and logo-fascinated lexicographer. Not so effin’ fast. The original of this piece appeared in 1996 for an academic journal The Critical Quarterly. In his ‘story of polari’ Fabulosa (2019) (a narrative elaboration of Fantabulosa (2004), a dictionary of Polari and Gay Slang), Prof. Paul Baker, now the vocabulary’s acknowledged expert, cited it as one of the few to attempt even an overview. I am the first to acknowledge its shortcomings and would direct you to his long-form studies. But my interest in Polari has never waned. It is thus, slangdar twitching off the dial, that I fell gleefully upon Richard Milward’s recent novel Man-eating Typewriter (2023), as far as I am aware the first work of fiction ever written almost wholly in what, as can be seen above, was for decades a truly mysterious lexis, and while not slang, then undoubtedly jargon.

The book’s first and abiding impression is the extent to which Milward has taken what was considered a micro-lexis, used by a specific sub-group of working-class gay men, and throughout a 536-page text, rendered it a functioning language.[6] Slang itself, while often described as such, is not a language, but in essence a wide-ranging collection of synonymies, focused on its obsessions: sex, drugs and rock and roll, if we are to interpret all three amusements in the widest possible way. It runs to around 150,000 terms and their differing senses. But it lacks the rules – of grammar, of spelling – which are seen as necessary for a ‘real’ language. The Polari lexis is even tinier (Baker’s 2019 glossary runs to around 575 terms). Yet Man-eating Typewriter has managed to take the form far beyond the contrived paragraph created for Gay News above. It might not be possible to reverse-engineer a Polari grammar from his efforts, but the lexis flows as if standard and my capella is duly tipped.

Lit. crit. assessment aside, from a purely lexicographical point of view, i.e. the wealth of examples of terms that are often unrecorded outside of glossaries, Milward’s novel is, to steal a word beloved of his anti-hero Raymond Marianne Novak, gloriosa. I have found 446 terms and/or senses, and as in any text, many are repeated on multiple occasions. I have no doubt that Paul Baker’s work was consulted, he gets an acknowledgement, but this is hardly a sin. We can deconstruct all sorts of authors - stand up Charles Dickens - and work out which slang dictionary was lying open as they penned this or that masterpiece. What is important - sit down Harrison Ainsworth, you’re embarrassing - is the author’s ability to disguise their seams. Richard Milward has achieved this with skill.

There are also a good number of terms which are neither listed by Baker nor in any ‘official’ Polari list. Seamless again, Milward has extended the lexis, by adding terms that, as does authorized Polari, play on French, Italian and so on. Thus, lavvy, life, and lever, a lip, may not be ‘legit’ uses, but they are based respectively on the synonymous French la vie, and (la) lèvre, and fit in perfectly. I have not, however reluctantly, added them to GDoS. This may be a mistake, but they do only seem to exist within the novel, and however skilfully conjured, they remain one-offs and have yet to escape to the wider world.

I don’t think they will. Like the thieves’ cant of the 16th century (briefly reported as popular in 21st century prisons), Polari, as successive generations discover it, is regularly touted as poised for a revival. Richard Milward has probably done that as well as possible. The novel is set in the ‘swinging London’ Sixties (though Novak’s anabasis sets out from the bomb-sites of the late 1940s East End and takes detours to Paris during the revolutionary événements of April ’68 and a brief foray along the hippie trail to Tangiers). If Polari had a prime then it would have been then, although, as noted, oncoming Gay Liberation would have no time for what was considered its obeisance to negative stereotyping. Polari had provided a code when codes were still necessary. That passed, though today’s sprint to the far right may yet enable it again.

[1] quoted in D. Cameron & D. Kulick Language and Sexuality Reader (London 2003) p. 92

[2] quoted in J. Green It: Sex Since the Sixties (London 1992)

[3] J.P. Stanley ‘When We Say “Out of the Closets”!’ in College English XXXVI:3 (Nov. 1974) p. 385/2

[4] The formation is well-established: the pseudonymous ‘Swasarnt Nerf’ (possibly the gay sexologist Edgar Leoni), co-author of the Gay Girls’s Guide (1949) listed ‘queen: [...] This popular and common word is found as a suffix (-Queen) in innumerable compounds, to denote a homosexual specializing in any activity.’

[5] I missed Morrissey’s hymn to the Dilly meat rack ‘Piccadilly palare’ of 1990. But the few words he uses – bona, vada, eek, riah – suggest a youthful absorption of Round the Horne rather than anything more hands-on.

[6] In this specificity it links more to Clockwork Orange, although its language Nadsat had no real-life existence and was built upon Anthony Burgess’s ludic adoption of Russian, than to such slang-dense texts as Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting and its successors, which remain wholly mainstream.