Slang is omnivorous. The great lexico-gastronome. Where mouth and guts meld as one, the chow-hound, the fang artist, the gobble-gut, the long belly, the hungarian, the firkin of foul stuff. Chews up, chokes down and spits out. The great subverter with an appetite like Gargantua (aged three that was already four bulls, fifty sheep, and three hundred partridges for dinner alone), with nothing sacred, from gourmet luxe to the the supermarket’s quotidian shelves. What a plenitude of nature’s bounty slang absorbs, meat and drink, fish and many veg, all else besides. I have a list somewhere. Were publishers, whose recording of the old divination seems long ago to have stuck at ‘we love him not’ and for whom I have run out of flowers to tear, I would cheerfully write at length of slang’s word-kitchen and its brimming pantry. But for today, and for no reason than the foodstuff is so well-known, I shall look at a single staple. The BLT. As explained in its intials, it combines bacon, lettuce and tomato and is America’s sixth most popular sandwich combo. (The hamburger is top, though some might not see that as a sandwich). While the ingredients are mentioned together in 1903, and the sarnie is obviously therefore a long-time regular on US menus, especially at lunch counters and similar, the abbreviation would not appear for maybe half a century.

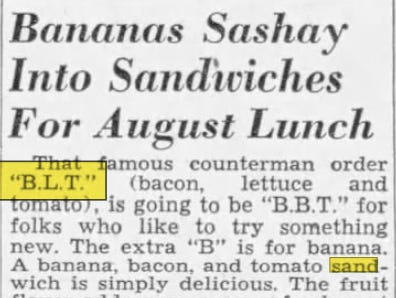

The first example I can find (and as ever I would love to be proved wrong) comes in the Lexington Herald-Leader of Kentucky, date 18 August 1956. It offers this:

The BBT was quickly 86’d but the BLT chomped on. The next mention, six months later and from the Morning Call (Allentown, PA) which on 24 September 1957 was noting, though not particularly regretfully, the decline of short-order slang:

Both pieces, note that ‘famous’ in 1956, make it clear that for countermen and customers, the BLT was long-established, for all that it was slow to gain print. As I say, I remain as ever open to improvement. The online search is not helped by the discovery that ‘blt’ is real-estate ad-speak for ‘built(-in)’ and OCR, while willing, is often easily confused and there is a limit to the false positives that I can face.

To finish my preliminaries, I should note that I have yet consciously to eat bacon. The ‘full English’ has never appealled, nor yet can I tolerate the British need to enwrap fatty rashers around their (presumably otherwise tasteless and often under-cooked) roast chickens. Obviously this (call it stupid, I assure you, I do) stems from kashrut, but equally from the fact that if I wished to escape a second religious indoctrination, this time via school, I had to prove myself a Christ-killer. Absent the risen Christ, and having no wish to drop trou and offer up the snip-cocked member, avowing to no bacon and allied pork products was a good short-cut. (I still see the five-year old me, first day at school and faced by a pallid, rubbery pink circle: spam. Kashrut aside, my mother was a good cook and spam would never have joined our parties. Unknowing, all too aware of Miss Chalk-and-Talk’s surveillance, I took a tiny bite and spat it out. Then waited for the hand of God to descend and snuff me out. No shit, I may even have looked upwards. It did not, but I was in tears and trembling when, school day concluded, my mother came to pick me up. My parents, who had wholly missed the trick, asked for me to be excused pig in future.)

None of which, forgive me, is quite germane. My aim here is the showcasing of slang and today I offer just that, by looking at what bacon/lettuce/tomato have been chosen to give us in the counter-linguistic lexis.

OK. To return briefly to the Morning Call, let us borrow from what they claim is the waitress and cook’s version of a ‘bacon, lettuce and tomato sandwich with mayonnaise on toast to go’. Strictly figuratively, let’s ‘burn a greasy BLT to walk.’

Bacon:

The ‘back and sides of the pig, “cured” by salting, drying, etc’ as stated by the OED (which also muddies the water by adding ‘formerly also the fresh flesh now called pork’ appeals to slang’s appetite as much as it does the the human. Among its names are Chicago chicken, Cincinnati quail and Kansas City fish; chuck wagon chicken, grunt and grunting peck, hobo’s delight, jockey's breakfast, overland trout and side-hill salmon, ruff peck, sheeny's fear and tiger (for streaky).

In an entry currently unrevised at Oxford the standard use of bacon is initially cited for 1330 and slang chimes in less than 40 years later with the first use of the term as human flesh and thence a human being. It is this bacon that we are desirous of saving.

The cites for this come fast and furious, but further senses will not appear for three centuries. In 1621 the counter-language turns meat to meat and assumes, quite rightly, that the human is focused on its genitals. Not just humans. Ben Jonson’s play The Gypsies Metamorphosed notes in 1621 ‘[The Devill] shifted his trencher as soone as he spies the Baud and Bacon / By which you may note the Devills a wencher’ while six years later John Shirley, in The Witty Fair One, tells his partner ‘I am untrussing as fast as I can [...] have at your bacon.’ Between the sheets (or elsewhere) seventeeth century lovers rubbed and scraped bacon although an angry wife might trim or badger it. In 1664, though in a single example only, from Thomas Jordan’s A Royal Arbour, a ‘gapeing countrey clown’ is promised a beating: ‘If we meet, I vow / Wee’l bang the bacon bastard black and blew.’ Such a rustic was also a bacon slicer. On campus in the 1990s bacon stood for a good-looking, sexy woman. As another synonym for meat, as in ‘X is my meat’, bacon could also mean prey, the desirable victim.

If slang first grabbed the term for sex, then fast behind comes that other obsession: bacon as money (its rich fattiness acting as a metaphor for wealth) appears in 1908 when the cartoonist and sportswriter T.A. Drogan (‘TAD’), voicing a hopeful pug, asks ‘Mr Claus’ for ‘one swipe at that Canuck. I need the bacon.’ In 1946 Mezz Mezzrow, jazzman and dope dealer, plays the food game in his memoir Really the Blues, noting the arrival in a club of ‘butter-and-egg men [rich dairy farmers from the mid-West] with plenty of bacon.’ Money also underlies another sense, the good life and material success, when to do well in material terms was to ‘get the bacon.’

The use of doubtle entendres would become part of 1920s blues lyrics. Lemons would be squeezed and bananas thrust into fruit baskets and for Bessie Smith, immortalizing a satisfactory lover, and specifically his penis: ‘He poured my first cabbage and he made it awful hot / When he put in the bacon, it overflowed the pot.’ Seventy years later, in his novel of a bent copper, Filth, Irvine Welsh cut to the chase: ‘Come taste the bacon baby, come taste that muthafuckin bacon!’

Thereafter it’s all compounds and phrases. The bacon bazooka (like its companions on the slab the mutton dagger and pork sword) is the penis (to slake the bacon is to masturbate) and bacon strips and vertical bacon sandwich the labia majora, while the practical the bacon hole is the mouth. Phrases offer pull or show bacon, to ‘thumb one’s nose’, the gesture itself known as long bacon (it can be made or pulled). To blanch the bacon is to remove one’s clothes preparatory, we assume to making bacon, another of the 1,750 synonms for fucking. If saving one’s own or another’s bacon is to escape safely from a place or situation (its antonym being logically to lose one’s bacon), to cook or fry someone’s bacon is to make trouble. To bring home or bring in the bacon is to deliver whatever is requested and required; the gravy can also be brought in triumph.

Finally we return to my own preoccupation: the odd-person-out is as useless as a slice of bacon at a Jewish wedding. This has proven durable, the first version being rare or scarce as pork chops at a Jewish wedding which, like such phrases as as much chance as getting a pork chop in a synagogue, as popular as a pork chop at a Jewish wedding (or breakfast or festival, picnic or in a synagogue), in more strife than a pork chop at a synagogue (also in more strife than a pregnant nun), like a pork chop at a bar mitzva, and rare as pork chops at a Jewish wedding all start life Down Under. America, however, offers silent as a pork chop salesman at a Jewish wedding and feel like a pork chop at a Jewish wedding or celebration; the pork chop can also be looking for a Jewish wedding, which suggests a certain deliberate aggravation, rather than feeling out of place. But all in all, we get the point: these nuptials, they’re full of coiners, and not of the stereotypical variety.

Lettuce:

No. Really. It’s not fair. We must, for so too has slang, set aside Britain’s egregiously, indefatigably absurd former prime minister, even if she is eternally linked to the most common or garden of salad vegetables, that lettuce which outlasted her time in office. Slang’s own term for lettuce is rabbit’s food while in short-order cooking, to add lettuce, tomatoes etc. to an order is to drag it through the garden. Australia has called it Nebuchadnezzar, a laboured piece of ‘wit’ based on that Babylonian king who went mad and ate ‘greens’ (in a second argotic tribute to the old boy, greens itself can mean sexual intercourse, in this case because the king liked them so much).

Meanwhile slang’s invention was surely only marginally taxed when it came to lettuce’s primary non-standard sense: it’s green, it must be money. Folding lettuce, pocket lettuce and lettuce leaves also make the cut. The image dates at least to 1903 when a villain (or so I presume, perhaps it was a demanding builder) in Karl Harriman’s novel The Homebuilders has the line ‘Unroll that bunch of lettuce you got in your mit and count out thirty-five bucks.’ On a grander level the term is used twenty-odd years later in John Dos Passos’ Manhattan Transfer where he uses the popular if implausible image of the wad of lettuce to suggest big bucks. Among other green vegetables thus recruited are parsley, kale, cabbage and salad itself.

The next sense that GDoS offers comes from US prisons and refers to prisoners who perform gang rapes. The only likely etymology is the standard English let us but unless this is cruelly ironic, permission does not usually enter this sordid picture. From there one moves to lettuce leaf, rhyming slang for thief. That compound also underpins lettie, South African gay slang for a lesbian, which has devolved the sneering lettiquette, behaving in a boorish manner, supposedly stereotypically lesbian. Electrice lettuce, stretching somewhat over-zealously, was for a moment a name for marijuana.

Tomato:

Slang does not seem to have bothered tomato much in terms of finding it synonymic names. The only one appears to be Jerusalem apple (God may know why, I do not), and most refer to commercial tomato sauce, including hemorrhage, red lead and tucker-fucker. Sugo di pomodoro this ain’t.

Whether pronounced as ‘tumayto’, ‘tumaydo’ or ‘tumahto’ slang’s first image is all about the luscious ripeness of the fruit. These sensual encomia create equate tomato with an attractive woman (sometimes a hot tomato with its overtones of passion and toughness; her neighbour the ripe tomato is more passive, ready for seduction and maybe marriage) and suggests the world of noir, whether books or black and white movies. The first recorded use I have is 1922, showing off flapper-speak and recorded in a Utah newspaper, ‘There was one wally I was goofy about, but while I was necking with him, Harry caught a tomato, so he says, Let’s blouse’. Women, real and otherwise, feature in subsequent senses: a prostitute (and her pimp), an attractive (possibly effeminate but not compulsory so) young man (where tomato is bracketed with alleged synonyms fruit, banana, meat, fish and cream), the vagina, and, irrespective of gender, the buttocks, whereby we may assume something of a bubble butt.

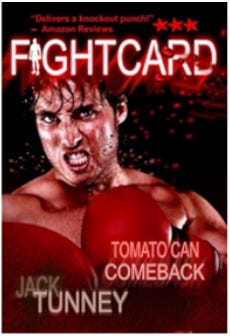

In the world of racial/racist stereotypes, tomato-picker means a Puerto Rican or Mexican farm labourer. More interesting is tomato can, in which all senses and compounds suggest the mass produced cheapness of the tinned product and its container. Thus it is the badge worn by a local or small-town police officer and reflects the cheapness of its mass manufacture. Alternatively it can refer to a second-rate boxer, with the punning suggestion that ‘he is easily crushed’, though his loss of blood, a red liquid, may play a part. Thus the US sports writer Peter Hamill in 1977: ‘They say he’s a tank artist, a tomato can, a guy who goes in the water for a few bucks.’ (The tank artist who goes in the water ‘takes a dive,’ a deliberate loss.) According to author Thomas Pluck, the tomato can’s only likely victim is a cream puff. Last and very likely least too is the tomato-can vag, aka can moocher, tomato can stiff and tomato-can tramp. In other words the bottom of the US tramp hierarchy. The etymology: apparently he drained the dregs of the empty beer kegs discarded outside saloons into a tomato can, equally empty but surely somewhat dreggy too, and knocked them back. As Godfrey Irwin explains in Tramp and Underworld Slang (1931) ‘later the same receptacle came to be used as a catch-all for begged or salvaged food.’ The can, if one of the larger sort, could double as saucepan and hold a mulligan stew (anything in the way of meat and veg that you could find or were given) over a jungle bonfire.

My search engine (https://www.newspapers.com/search/) won’t allow that search (too many single letters). Nor, it seems, does it hold the Boston Herald. Would it be too big an ask for you to copy the actually quote.

Thank you. It does somewhat pour, and the aim is to pack in as much info as possible, but I do a lot of tweaking thereafter. Nearly 50 sarnie synonyms in GDoS. 'Giorgio Armani' (which rhymes), 'sammie', 'sanger' and 'sango', 'pig in the mud' (ham with mustard) and 'wad' offer a flavour. 'Radio', a toasted tuna fish sandwich on white bread, leaves me feeling 'two sandwiches short of a picnic.'