K is For...

Kazi, not to mention Cahsy, Carsi, Carzy, Cawsy, Karzi, Karzie, Karzy, Kazi, Kharzi, Khazi)

[Another excerpt (see for instance here) from my 2008 effort Getting Off at Gateshead (the only book I have essayed wherein I forget the title - not my choice - and had to write, at proof stage, an envoi which justified its existence. It was all about coitus interruptus and played on railway stations). Herewith the cophrophilial letter ‘K’.]

The Khasi of Kalabar: May the benevolence of the god Shivoo bring blessings on your house.

Sir Sidney Ruff-Diamond: And on yours.

The Khasi of Kalabar: And may his wisdom bring success in all your undertakings.

Sir Sidney Ruff-Diamond: And in yours.

The Khasi of Kalabar: And may his radiance light up your life.

Sir Sidney Ruff-Diamond: And up yours.

Carry On Up the Khyber (1968)

Yes. Gods did indeed once walk among us. But no, this will not be an assessment of the Great Game as played out amidst the North-West provinces of the Raj, and its grim warning for the contemporary world, nor yet (you wish) a dissertation on Carry On movies. The letter is K, the word is khazi and our text today brings light to bear upon the many terms for lavatory (or as they say in those areas of society unblessed by the late Mitford Sisters, the toilet) in the slang vocabulary.

As befits so vital an amenity, the khazi is but one of a number of allied spellings: carsey, carsi, cawsy, karzi, karzie, karzy, kazi and kharzi, which show, among other things, yet another example of what happens when one attempts to set down on paper that which usually appears but between the lips. But if the adventures of Sir Sydney, Private Widdle, Bungdit In, Major Shorthouse and of course the Khazi himself are not canonical, what, quite frankly is life worth? so for our purposes, khazi it is.

Based on Italian casa, a house, it arrived via Polari, the language of the stage (and latterly the camper end of homosexuality) in the mid-19th century. It is one of a number of available definitions: others include a brothel, a thieves’ den, a pub and simply a house. And the khazi, figuratively, can describe any messy or otherwise unappealing place. Casa is also the root of the earlier (from the 17th century) case, which again offers us a selection of sheltering roofs: a house, a shop or warehouse, a brothel (or case-house, owned by a case-keeper and wherein works the case-fro or case-vrow – from German frau) a ‘thieves; kitchen’, and, of course, a lavatory. To crack a case is to break into a house (quite the opposite of Plod’s variation) while to go case or case-o (or have a case) with are to live with someone, or, in an era that pre-dated the modern call-girl, to work as a genteel prostitute, from a flat, rather than walking the streets.

But back to the khazi and its many peeers.

Although bog, crapper and dunny (the last best-known Down Under) have come to take precendence, one of the oldest recorded terms for a lavatory seems to be ajax. This term, with no apparent link to any aspect of defecation, was popularised by the Elizabathan courtier Sir John Harington (c.1561–1612) in his pamphlet The Metamorphosis of Ajax (1596), a light-hearted plea for the introduction of the water-closet. Perhaps a little too light-hearted: such was its supposed coarseness that a less than amused Queen Elizabeth I temporarily banned its author from court. Nor does it seem that Sir John was the first to use the word: Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost is dated a year earlier, and there we find – the bard being as admirably devoted to puns as ever, ‘Your lion, that holds his poll-axe [well, work it/them out] sitting upon a close-stool [itself a primitive WC], will be given to Ajax.’ The greater likelihood is that Harington too was punning: on ‘a jakes’ which piece of toilet talk has been recorded as available since at least 1533. Jakes (also jacque’s – a hit at the French or just 16th century spelling? – jake and jaxe) has given jacks (still popular in Ireland), and the jake- or jack-house. The jakes-farmer or -barreler was he who emptied the privies. But such an etymology wasn’t at all what Harington himself wanted,. and he declared otherwise. Though still unable to resist the pun he conjured up the image of a constipated old fellow, astride the pot, straining with all his might and crying ‘Age aches, age aches.’ Maybe Gloriana was right – though ‘coarseness’ be damned.

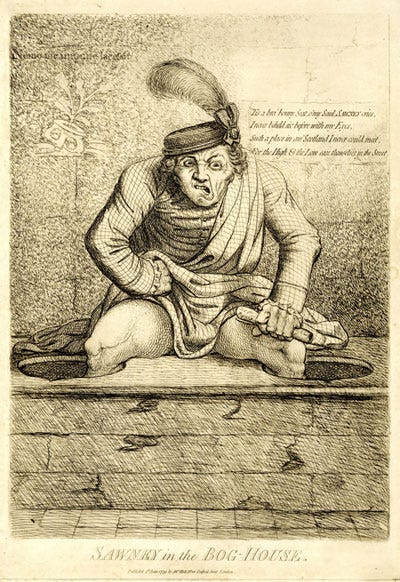

Abandoning Merrie England to its own devices, one moves on to bog, bogs or originally boghouse, and creation, at least as a word, of the mid-17th century where it is listed in the first of a succession of slang dictionaries as a synonym for privy. It has always been, as the original OED put it, ‘a low word, scarcely found in literature, however common in coarse colloquial language.’ Boghouse would bring, around 1731, Merry-Thought, or, The Glass-Window and Bog-House Miscellany by one ‘Hurlothrumbo’ wherein, among much else, one finds the verb ‘poop’ but not in the defecatory sense, rather as another synonym for rear-entry intercourse. There is no mystery to the etymology: one need but picture the environment. That’s right: boggy. And as a well-used term, bog has created its own small group of compounds: the bog-blocker, a non-specific term that denotes anything particularly unpleasant (the image is of some obstruction, probably faecal, blocking a lavatory), the bogbrush, with which one cleans the bog (a bog brush upside down is a cropped, spiky haircut, supposedly resembling a lavatory brush), bogroll and bog bumf, lavatory paper, bog queen, a gay man who frequents public toilets for sex, a bogshop, an outside privy and bog wash a youthful initiation rite whereby the victim has their head pushed into a lavatory pan which is then flushed; the 1968 movie If… set in an English public school may be the sole on-screen portrayal – it costs serious money to get that kind of character-building.

After the bog, crap. Crap itself means excrement and its roots lie in the Dutch, krappen, to pluck off, cut off or separate and old French crappe, waste or rejected matter, siftings, particularly ‘the grain trodden under feet in the barn, and mingled with the straw and dust’ (OED) and dust itself has also been claimed by slang for both dung and dosh); the ultimate root is Medieval Latin crappa, crapinum, the smaller chaff. Its earliest, 17th century use referred to money and can thus be seen as linked to one slang definition of dirt as dough (and a futher etymology brings in French crape, dirt). The excrement meaning arrived in the mid-19th century. The first lavatorial uses for crap are obviously contemporary, and are found as crapping-ken or -casa (i.e., ‘shitting house’) and crapping castle, that minuscule but still vital part of the Englishman’s home. The odd one out is croppenken, and its etymology throws all the rest into confusion. Its first use is in 1674, included in Richard Head’s explication of 17th century lowlife, The Canting Academy, as ‘Croppinken A Privy or Bog house.’ Croppen itself is based on dialect croppen, a tail and ultimately from standard crop, to cut off – and thence back to the origins of crap.

Crap is the unequivocal root of craphouse, a lavatory, any unpleasant, dirty place and in US show business, a a small, unfashionable venue. Craphouse luck is unexpectedly good luck while the craphouse rat, cousin to the better-known denizen of the shithouse, and condemned through the usual prejudices, stands as a byword for cunning or dirtiness.

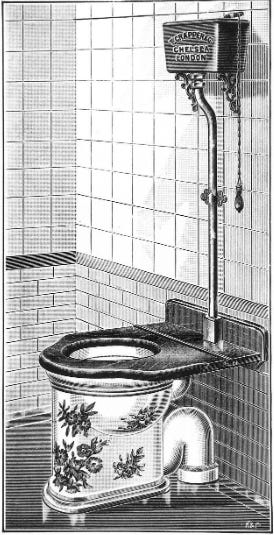

And while I can only apologise in advance to the world’s popular etymogists for what follows, crap is also the root of crapper, a lavatory. Rather, like it or not, than Mr Thomas Crapper (1836-1910) a doubtless admirable plumber whose manhole covers adorn Westminster Abbey to this day, but who, despite much theorizing, was not even the inventor of the flushing water closet. He popularized it – vastly, and we should all be grateful for his addition of the floating ballcock (one his nine patents) – but the crapper, as in the basis of his fortunes (he even boasted a royal warrant, from Edward VII, though sadly – fittingly? – the firm went into liquidation in 1969) comes from crap.

And just to confound matters, crapper as lavatory did not enter the vocabulary until, the later 1920s; meanwhile the US campus, in 1900, had already used the word to describe as an unpleasant person, and US criminals, in the 1920s, extended the put-down to assail a prison. Not until 1927 do we find a reference to what has become the usual meaning. Since then, more developments: the crapper can be the anus or buttocks and in the sense of talking crap, a braggart or a liar. The crapper dick was a plainclothes policeman who specialized, until such entrapment was finally outlawed, in hanging around public lavatories in the hope of catching gay men having sex; the same name was used for an extortionist who poses as a policeman to blackmail homosexuals. In the crapper means finished, failed, rejected, abandoned or rendered useless; a New Zealand variation is in crapper’s ditch.

While we’re in the antipodes, on to the dunny. Or, long before we reach Australia’s adaptation, the dunnaken, dunegan, dunnakin, dunnick, dunnikan, dunniken, dunyken, donicker, donigan and donagher, all of which come from the old word danna, dung and ken, a house. Yes, it’s another shithouse. It gives the American underworld’s donegan or dunnigan worker, a thief who hangs around public lavatories, hoping to steal from discarded coats or take parcels or anything else that has foolishly been put down. But its real gift is the dunny or dunnee, a term that is first recorded, in a fine example of Australia’s pervasive multiculturalism in Xavier Herbert’s Capricornia (1938): ‘Chineeman him no-more jiggel — him no-more lat belonga dunny’ though more pleasing (not to mention understandable) is a 1948 example ‘You wasn’t here when the dunny blew up.’ Along with dunny there’s the dunny cart, a vehicle used to remove excrement, the dunny man, who drives it; dunny roll, lavatory paper, the dunny-brush which like the bog brush can extend into being a term of abuse, the dunny budgie, a fly that can be found in the privy, the budgie referring to its size and noisiness (the Lucky Country, eh?) and the usual put-down is aimed at the cunning dunny rat. To flap like a dunny door in a high wind is to act in a panicky, nervous manner, unlike bang like a shithouse door in a gale, that male term of ultimate sexual approval, there is no sense of feminine allure.

The loo, considered quintessentially middle-class and even squeamish, has a number of possible origins: French l’eau, water; the bordalou, a portable commode, resembling a sauce boat and carried by 18C ladies in their muff; SE leeward, the side of a ship turned away from the wind and as such the side over which one would urinate or defecate; or an abbreviation of or pun on Waterloo, whether the station or the battle it commemorates. Socially the opposite, and perhaps the most recent popular term is the shitter, from, of course, shit. As well as a lavatory it can represent the anus, any form of disusting place, e.g. a prison’s punishment cell, as well as one who defecates in public, or, as a thief, who likes to excrete inside the places he robs; in coprophiliac sex (if you don’t know you sure won’t need to ask), it is one who defecates on their partner.

Having laid out the primary lavatories, it seems suitable to take time and run down the rhyming slang that they have accrued. (By the way, khyber, in khyber pass, gives us a rhyme for the buttocks or anus, or more coarsely, the arse). Shitter gives banana fritter, and both the country and western star Tex (1905–74) and his wife the movie actress Thelma Ritter. That they can also rhyme with bitter (beer) is probably no compensation. The Muppet Show’s Kermit the Frog presumably has no objects to rhyming with bog, nor, logically, could Star Trek’s captain’s log. The boxer Gene Tunney (1898–1978) rhymes with dunny, as does the phrase, here transmuted into a noun, the don’t be funny. The late Frank Zappa is a crapper, the tennis champion Ilie Nastase offers khazi, Mrs Chant rhymes with ‘my aunt’, to visit whom is to go to the loo, although slang’s ‘aunt’ is more usually associated with menstruation. Mrs Ormiston Chant (1848–1923) was well-known moralist, and this was doubtless one of her earthly rewards. Last of the proper names is the mystifying, at least to Brit ears, Angus Armanasco. This one, memorializing the Aussie racehorse trainer Angus Armanasco (1907–2005 rhymes with brasco. Brasco? It’s ‘where the brass knobs go’. Boom! Boom!

More rhymes can be found in house of wax (and wax itself can mean excrement), the jacks, rag and bone, Rosie O’Grady’s, the ladies (lavatory), savoury rissole, a ‘pisshole’, snake’s hiss, a ‘piss’ but also a lavatory, lemon and dash, in which one has either a wash or a ‘slash’, the family tree (rhymes on lava-tor-ee), one and two, the loo, and the throne, i.e. the lavatory bowl,

The idea of the throne gives another aspect of that place where the king or queen goes on foot: the centrality, at least of the public lavatory, to certain areas of gay life. The throne, or the king’s throne or throne room is the WC, and while on the throne means defecating, a pretender to the throne referred to a vice squad policeman who poses as a gay man to entrap actual ones. (In times of war or national service it also identifies a heterosexual who poses as gay for the purposes of avoiding the draft or call-up.) Thus, pursuing the regal imagery, to abdicate (the throne) is for the reigning ‘monarch’ – in this case a queen? – to leave a public lavatory in which he is soliciting to avoid interrogation by its attendant or wrose still a policeman and to be dethroned is for a gay man to be ejected from the public lavatory where he is looking for sex.

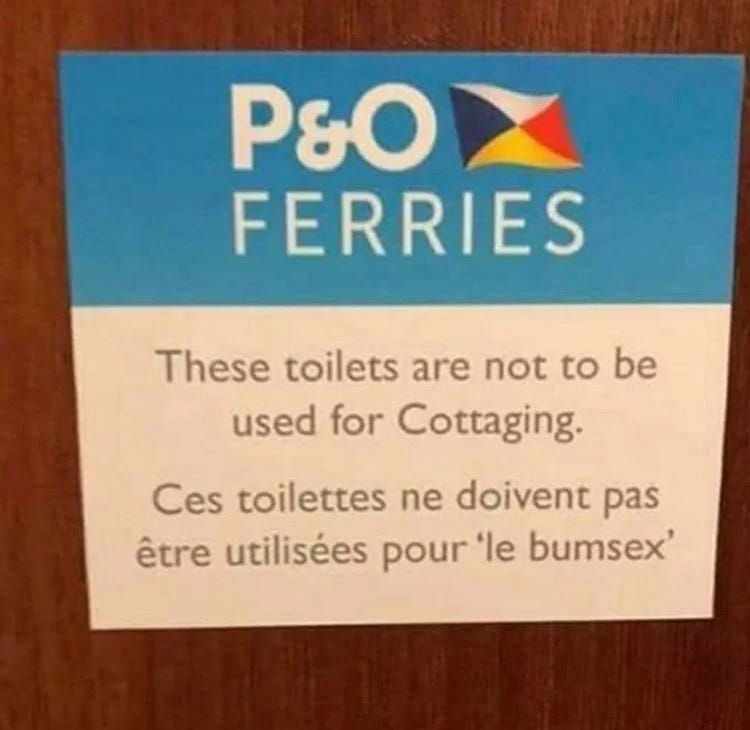

The public bogs that provide such thrones have their own names, the most important of which being the cottage. This was categorized by J. Redding Ware in his Passing English of the Victorian Era (1909) as a usage of ‘fast youths’ and attributed to ‘the published particulars of an eccentrically worded will in which the testator left a large fortune to be laid out in building "cottages of convenience"’ It may even be true, and so far the OED has yet to help us. As a public convenience or indeed anywhere gay men meet (other than actual bars) it gives cottage queen or cruiser, a male homosexual who solicits in public conveniences and cottaging, frequenting such gathering places. Almost as well-known, though perhaps no longer, as cottage was tearoom, which may have been based on tea, meaning urine (the tea-voider had meant a chamberpot many years earlier), but was more likely just a camp image of a load of queens sitting (or rather standing) around as at a tea-party. The tearoom hosted tearoom queens and tearoom cruisers, who searched for tearoom trade, a term that was both generic for the world of sexual assignations, pick-ups and consummation practised in public lavatories and for the men who enjoy being fellated there.

Synonyms include cafeteria (you can get ‘something to eat’), a carousel (one goes round and round looking for sex), a fairy house or joint and fairy’s phonebooth, a service station, a lollipop (the sucking), and the zipper club, based on the lowering of the zipper of one’s fly in order to enjoy quick, sponteanous oral sex, i.e a zipper dinner. To visit a cottage is to go on a milk run – milk being semen. Finally South Africa’s slangpark. An apparently odd word – do they just talk dirty to each other? – until one appreciates that slang, in Dutch, means a snake – in German (and 19th century British slang) it can be a watch-chain – and that for South African gay men, the word stands for the penis. Thus the ‘snake-park’. Simple, is it not.

And the lavatory has another vital function: as a repository for vomit, at least in the world of the US campus. In every case the image is the same: the commode-hugging drunken suffererer, prostrate upon their knees, head deep in the toilet bowl, gastro-intestinal functions working at full tilt – albeit in reverse. Thus we have worship at the white altar, to vomit, drive the (porcelain) bus, and make love to the lav or to the loo. One speaks or talks on the big or great white telephone and may address oneself to God or more usefully to ralph, an onomatopoeic term that –go on, say it – sounds just like an upchuck. And the while the bowl is probably not made of actual porcelain (today’s internet offers only sinks tat are thus fashioned), one can also pay one’s respects to the porcelain god or goddess, as well the enamel god. Terms include kiss, bow to, hug, make love to, pray to, and worship the porcelain god, and in all cases goddess. That big white telephone can be a porcelain telephone too.

Other than garde-robes, a form of castle storeroom which harboured some kind of seat above a long and hollow drop (and where one also stashed one’s clothes - moths apparently fled the noxious vapours), the earliest lavatories, the boghouse included, were external structures, or privies and it is among these that are found some of the first names for any kind of lavatory. One of them is probably the oldest of all such recorded terms, slang or otherwise, and which dates from the 11th century: the gong-house, a word that is based on AS gang, the act of walking and which as such is both euphemistic and, however remotely, an ancestor of the child’s plaint, ‘I’ve got to go’. The gong farmer or jakes farmer was a cleaner-out of privies, a nightsoil man. So too the gold-finder, gold being the colour of excrement, which term quasi-euphemised Tom Turd-man, another gatherer who worked in tom turdman’s fields and tom turdman’s hole, the dump where the nightsoil is deposited.

Other early terms include the coffee-house or -shop, both looking to the ‘coffee-coloured’ contents of the cesspit, spice island, which played on its stench, the necessary house or (house of) office, the chapel or office of ease and the house of easement, the convenient or convenience (one that has lasted) and my uncle’s, although that phrase was far more commonly associated with a pawnbroker’s. A wedding (perhaps based on SE weeding) was the emptying of a privy while to go backwards, either from the position of the anus on the body or the privy behind the house, was to visit the bog, while a smokeshell was the steam that arose from its still warm contents.

Perhaps the most interesting was cuzjohn, as used in the 1734-5 editions of Harvard College’s regulations: ‘No freshman shall mingo against the college wall or go into the fellow’s cuzjohn.’ John is presumably its abbreviation. The word mingo, to piss, is a direct borrowing the synonymous Latin. Jericho is otherwise a figurative place of retirement, banishment or concealment, i.e. ‘let [him] go to jericho’ while jerry, a chamberpot, is based on SE jereboam, a double magnum of wine and is extended as jerry-come-tumble, a lavatory and jerry-go-nimble, diarrhoea. Egypt, another synonym for ‘elsewhere’ (hence Bumfuck, Egypt the epitome of ‘far away’) is a natural qualifier. Well-known in America, but not elsewhere is the Chic Sale, named for ‘the champion privy builder of Sangamon Co., Ill.’ and best known for his book The Specialist (1929). The throttling pit is the place – what else? – where one chokes a darkie.

Privy (from old French privé, intimate, personal) itself plays a role in slang: the punning privy council is an outhouse, and a privy-queen is a gay man looking for sex in or around public lavatories. The privy counsel, however, is the vagina, otherwise the privy paradise, privy hole and indeed privy. (Whether these smear the vagina as ‘dirty’ or whether they point up its role as a ‘private part’, or indicate its place ‘at the front’ of the body are all open to suggestion.) A last round-up offers California house, backy, dumpty-doo and dumpy (variations on dunnee), hoosegow (from Spanish juzgado and far more usually meaning a jail) and bringing us back to the world of Carry On, kybo, which abbreviates Khyber pass, the arse. The library refers to the catalogues that were hung in the privy as toilet paper. And a little piece of history: the Cockney's luxury: breakfast in bed and using the pot, rather than leaving the warm house for a trip to the outdoor privy. The po usually means a chamberpot, from the ‘affected’ euphemism pot de chambre, but the phrase after you with the po, Jane referred not to a shared potty, but to the need to take turns in using an outdoor privy; in time it would apply equally to the indoor facilities.

The chamberpot, a miniature, portable lavatory if you will, was once a normal piece of bedroom furniture, the gazunder (i.e., the bed) as one nickname had it. Space precludes the listing of every name, but some are worth a little exploration.

Probably the earliest is the jordan, found in the 14th century. Some have tried to link it to jordan-bottle, but more likely was the synonymous standard use of jordan: a pot or vessel formerly used by physicians and alchemists; such pots might often have held urine for analysis. The looking glass carried a similar image, both one’s reflection in the urine, as well, possibly, as the attention paid by contemporary physicians to the urine itself. Thus the 18C riddle: ‘Q. Why is a Chamber-Pot call’d a Looking-Glass? A. Because many rarely see their Faces in any other.’ The pisspot (or pee-pot, piss-barrel, pissing-pot) had its brief moment of fame in 1710 when there appeared in Clapton near Hackney, then a village near London, a house (perhaps a tavern) known as Pisspot Hall. As Francis Grose explains, it was ‘built by a potter chiefly out of the profits of chamberpots, in the bottom of which the portrait of Dr Sacheverell, preacher, was depicted.’ Dr Henry Sacheverell (c.1674–1724) was a High Church and high Tory cleric, who preached two sermons in 1709 that resulted in his impeachment on charges of seditious libel. He was condemned, but received so light a punishment as to claim victory. His supporters were as vehement as the unknown potter. The Rector of Whitechapel commissioned an altarpiece in which the figure of Judas Iscariot was represented by that of the Dean of Peterborough, one of the Doctor’s most virulent critics.

A similarly ‘biographical’ chamberpot was the twiss. In this case the victim was one Richard Twiss (1747–1821), an English writer who had authored a highly critical ‘Tour in Ireland’. To take their revenge the Irish produced a chamberpot with a picture of Richard Twiss inside it, beneath which was inscribed the rhyme ‘Let everyone piss / On lying Dick Twiss’. Finally the late 17th century’s Oliver’s skull, a reference to the late oliver Cromwell, of far from blessed memory. No rhyme seems to have accompanied it, but patriots could also purchase a pot with a bust of Napoleon within. A text read simply ‘Pereat’: let him perish.

Across the Atlantic the mid-19th century name was, among others, the badger, giving rise to a practical joke – the badger fight or pulling the badger – whereby a full pot was emptied over some unfortunate’s head; this was known as christening them. Thigh-slapping stuff, to be sure. The 19th century UK offers jemima, which doubled as a serving maid and the chamberpot – underlining her duties in removing it and the 20th charley or charley whitehouse, i.e., the whiteness of the shitpot. It (otherwise the genitals or sex) was a euphemism, as was Sir John (otherwise a parson or a penis). The stinkpot, also the vagina, was not. Chamber music represents the sound of urine hitting the pot, and the urinating penis is seen in member mug, master can and jockum gage. One last contender: the remedy critch, which is based on SE remedy, ease and critch, an earthenware vessel; ultimately from cratch, a stable hayrack and thus a crèche; the term is used as such in early descriptions of Christ’s birth.

I always liked ‘talking on the great white telephone’, for the humorous suggestion that it was somehow talking back…

Holy crap!