Highway to Hell

‘You jovial sailors’

[The original version of this appeared - as ever, I have not resisted a little expansion - in Sam Llewellyn’s Marine Quarterly (https://www.themarinequarterly.com) in 2015. The MQ is more usually dedicated to the serious and practical (and to this landlubber1 often fascinating) side of sailing on every variety of scale; slang and its environs, on occasion, are dragged from the bar-room’s floor to offer a jester. I might have included it in my ‘London in Slang’ series, but, as is so often slang’s fate, there was no-one in the corner jotting down linguistic notes.2 ]

‘You jovial sailors, one and all,

When you in the port of London call,

Mind Ratcliff Highway and the damsels loose,

The William, The Bear and Paddy's Goose.’

Popular Song c. 1830

It is truly conspicuous by its absence. Like a house that has borne witness to a killing of more than usual foulness, it has been razed and the site rendered extinct beneath fresh concrete and tarmac. It has utterly disappeared, even unto its proper name. There may be ghosts, but it seems that they must not be permitted to find a way back.

The Ratcliffe Highway. Nineteenth-century London’s sailor central. Not a vestige left.

The alms house, the school, the merchant’s houses and the warehouses of its first incarnation. The avenue of elms that once lined the street, the people that strolled it. The minatory gallows erected on a hill in neighbouring Limehouse (named for its limekilns burning chalk for builders’ lime) in 1440 for the hanging in chains of water-thieves (known as ark-ruffians3), their rotting corpses visible, London’s Elizabethan chronicler John Stow tells us, ‘farre into the riuer Thames’.

The William, the Bear, the Gunboat, the Angel & Crown, the Sailor’s Saloon, the Hole in the Wall, the Mahogany Bar: all the pubs, lodging-houses and semi-brothels of its 19th century notoriety. Most notorious of all Paddy’s Goose, a nickname that teased the stereotypically stupid Irishman for whom all swans are but geese and who allegedly mistook its real name, the White Swan. For that once glorious emblem of debauched spoliation was reserved the most heart-rending of all futures: purchase by a temperance mission.

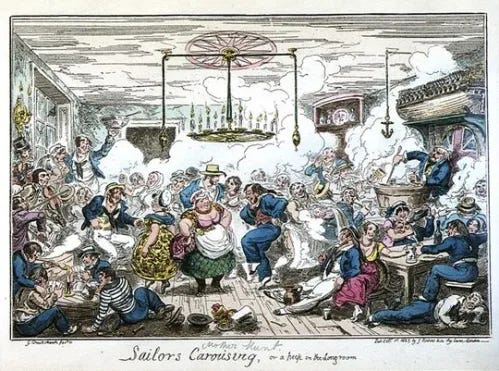

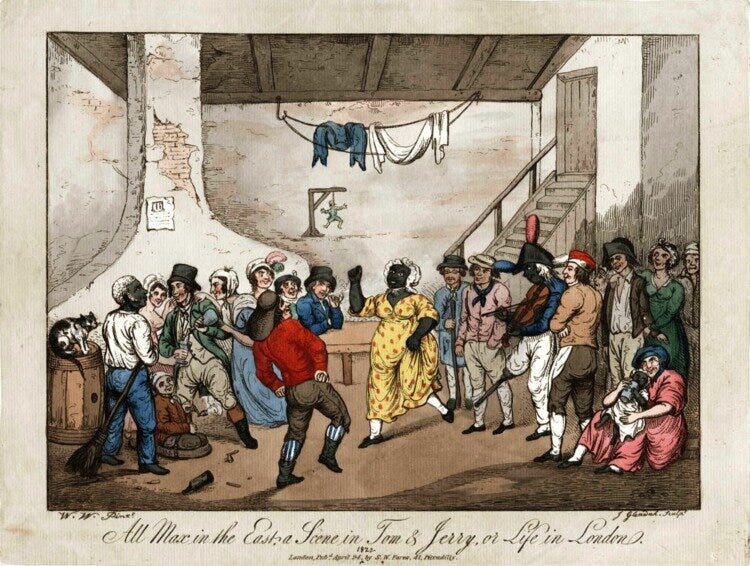

And, for once paying out to visiting sailormen rather than draining their purses, Jamrach’s, the wild beast emporium where fresh off the boat returnees sold those creatures — mainly parrots for whom the rule was the more psittacocal oaths the better the price — that they’d brought back from foreign climes. Gone too are those that walked the streets: Damaris Page the ‘Great Bawd of the Seamen’ c. 1650, and her less distinguished but equally industrious successors Cocoa Bet, Dandy Jane or Black Sal (who, shown by George Cruikshank in her spotted yellow frock,4 danced a measure with Bob the Coal-Whipper as slumming Corinthian Tom and his pals look on in the ‘All-Max’ chapter of Pierce Egan’s best-selling Life in London).

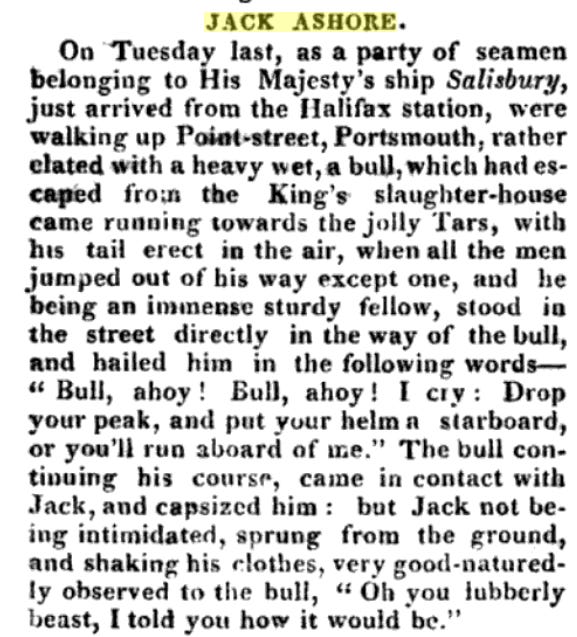

And last but anything but least, Jack. Jack Ashore5. Jack in his seemingly inevitable role as naïve prey for pimps and crimps, whores, pawnbrokers and greedy chandlers, sea-faring innocent among the rapacious landsmen. Not for nothing is Jack Aubrey, co-star of Patrick O’Brian’s 20.5-book (the last unfinished) saga of the early 19th century Royal Navy, so called.6 If Jack is the noble, fearless, not invariably chaste nor sober sailorman of every cliché when he’s sailing and fighting his ships whether in the chops of the Channel or far round the Horn, on shore he is almost embarrassingly incompetent, prey to every conman, flimflam artist and scheming young woman who come his way. Not for nothing too, perhaps, are some of slang’s gullible suckers named for marine creatures (surely out of water): gudgeon, lobster and fish itself.

It thrived once. It roared and raved and thrilled and horrified almost without equal in the great, world-dominating metropolis. It is all gone.

_______________

Ratcliffe-highway-and Ratcliffe-highway by night! the head-quarters of unbridled vice and drunken violence-of all that is dirty, disorderly, and debased. Splash, dash, down comes the rain; but it must fall a deluge indeed to wash away even a portion of the filth to be found in this detestable place. Like a drab, it lies side by side with the river, who holds it in a foul embrace, kissing its rottenness with slimy lips, and receiving into its broad bosom a portion of the corruption it contains.

Watts Phillips, The Wild Tribes of London (1855)

The Ratcliffe Highway, in East London, connected the Tower to Shadwell. It took its name from the ‘red cliffs’ of a natural landing point on the Thames between the Wapping marshes and the Isle of Dogs, which had been inaugurated by the Saxons. By the 16th century it was a prosperous area, and its quays the start of many voyages of discovery, typically those of Hugh Willoughby and Martin Frobisher. Ships’ captains built themselves houses there, as did those who built or supplied their vessels and the merchants whose goods filled them. All this was destroyed in 1794 when a fire ran through the narrow streets and wooden houses. The rebuilt highway gained a vastly increased population but the well-to-do moved out, to be replaced by relatively impoverished dockers, mainly Irish, and a down-market rag-bag of those whose own incomes depended on stripping sailors of theirs.

Though Jack was not always a victim. In late 1811 a sailor, one John Williams, killed a shop-keeper, Mr Marr, and his wife and their shop-boy. A few days later it was the turn of a publican, Mr Williamson of the King’s Arms in Old Gravel Lane. Again, both wife and servant joined him. Williams was captured soon afterwards, hiding out in a sailor’s boarding-house. He killed himself in his cell the same night. Deprived of a trial and more importantly an execution, an enraged and terrified public demanded that justice, or a variation thereupon, was still seen to be done. The murderer’s body was placed on a platform in a high cart, with the mallet and ripping chisel, with which he had committed the murders, by his side, and driven past the houses of his victims. A stake was then driven through the demon’s chest and his carcase thrown into a hole dug at the junction of the New Road and Cannon Street Road. It took a while for the general panic to abate: locksmiths prospered and there was a rush on rattles, used to summon help; the writer Thomas de Quincy, otherwise known for his celebration of opium, used the killings as a basis for his essay ‘On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts.’ The modern crime writer P.D. James memorialized the gruesome events in The Maul and the Pear Tree (1971).

Nor were the regular tides of visiting foreign matlows to be trusted. As the East London Observer informed its readers in 1857, not an inch of the Highway was safe:

Either a gin-mad Malay runs a much [i.e. amok] with glittering kreese [kris], and the innocent and respectable wayfarer is in as much danger as the brawler and the drunkard; or the Lascar, or the Chinese, or the Italian flash their sea knives in the air, or the American ‘bowies’ a man, or gouges him, or jumps on him, or indulges in some other of those innocent amusements in which his countrymen delight.

In 1878 the social observer Walter Thornbury could call it ‘the Regent Street of London sailors, who, in many instances, never extend their walks in the metropolis beyond this semi-marine region.’7 Whether he was deliberately referencing contemporary Regent Street’s thriving population of prostitutes is unknown, but the working girls were undoubtedly drawn to an area so popular with men who arrived both frustrated by months of celibacy and well-supplied, at least for a while, with the means to rid themselves of it. For observers, however, it was a fine example of hell on earth.8

All the dregs and offscourings of male and female humanity swarmed in the foul and filthy dens of the Highway, ready to prey on the lusts, the follies, and the trustfulness of the sailor. Before his ship had fairly docked a horde of boarding-house keepers’ and tailors’ runners were over her rail, insinuating themselves into the good graces of the seamen, plying them with rotgut liquor, and speedily gaining the reputation of being the best of good fellows and a real friend to sailormen. And off rolled poor Jack to his ‘home from home’ in the filthy purlieus of the Highway, there to remain half drunk until his pay was spent and he was well in the debt of his erstwhile hospitable host, who then sold him to an outward-bounder like so much cold mutton.

C. Fox Smith Sailor Town Days 1954

Around mid-century it seemed that every social commentator and journalistic explorer felt duty bound to make their way East so as to dip a toe – depth of dip varying as to threshold of squeamishness– into the foetid squalor before running home to comment excitedly - moralizing parentheses administered as to taste - back in the comfort of one’s West End study. The initial example of such slumming, admirably devoid of cant or moralising, had been Tom and Jerry’s fictional excursion of 1821; by mid-century there was a regular procession.

All saw much the same. There was Jack, often sporting a skin tone other than British or north European pink and representing most of the world’s navies, state or merchant. There were pubs which ensured that he was usually drunk and invariably spendthrift, though the kinder lodging-house owner, pub landlord or even whore would take his wallet, and ensure that not everything, other than the invariably padded bill, was stripped from it.

There were the girls, parading in costumes that while unfashionable, were undoubtedly geared to the task: short night-gowns and bed-jackets. They were drunk too, but not so much as to preclude the cheating of their hapless companions.

The female of the locality in question is seldom seen dead drunk, as it is termed. Such a condition is almost impossible to her. She is far advanced beyond the weakness of succumbing easily to the influence of intoxicating fluids — if she was ever subject to it, which is doubtful-bred and suckled on gin, as she probably was, and weaned on gin and bitters. […] It is marvellous that even spoony ‘Jack ashore’ can discover anything in the least attractive in her. In language and manner she is as coarse as a coal-whipper, and the guiding principle of her shameful existence seems to be to make known her contempt and abhorrence of all that is modest and womanly.

James Greenwood ‘Down Radcliffe Way’ 1875.

Greenwood was censorious, such horrid revelations were the foundation of his ‘made my excuses and left’ career. Not everyone was so affrighted. George Augustus Sala, one of Dickens’ ‘young men’ on Household Words and a dedicated bohemian journalist in his own right, was far more tolerant.

You are not to suppose, gentle reader, that the population of Ratcliffe is destitute of an admixture of the fairer portion of the creation. Jack has his Jill […] Jill is inclined to corpulence; if it were not libellous, I could hint a suspicion that Jill is not unaddicted to the use of spirituous liquors. Jill wears a silk handkerchief round her neck, as Jack does; like him, too, she rolls, occasionally; I believe, smokes, frequently; I am afraid, swears, occasionally. […] Jill has her good points, though she does scold a little, and fight a little, and drink a little. […] She takes care of Jack's tobacco-box; his trousers she washes, and his grog, too, she makes; and if he enacts occasionally the part of a maritime Giovanni, promising to walk in the Mall with Susan of Deptford, and likewise with Sal, she only upbraids him with a tear.

G.A. Sala Gaslight & Daylight 1859

And Jill, or Sal or Susan did, all too often, leave him something by which he might remember them.

Here's luck to the girl with the black curling locks,

Here's luck to the girl who run Jack on the rocks,

Here's luck to the doctor who eased all his pain,

He's squared his main-yards, and he's a-cruising again.

It was not all sex, nor even drink. There were drugs. Next-door Limehouse would gained a leprous renown as home of the evil, if fictional Dr Fu Manchu, but the Chinese population was already in place 50 years earlier; and with ‘Johnny’ came opium. The visiting slummers tip-toed, or so they claimed, around intoxication’s farthest edges, but Jack was happy to indulge and Charles Dickens Jr, in his Dictionary of London (1879), offered the requisitely horror-struck description of:

…the little breathless garret where Johnny the Chinaman swelters night and day curled up on his gruesome couch, carefully toasting in the dim flame of a smoky lamp the tiny lumps of delight which shall transport the opium-smoker for awhile into his paradise. If you are only a casual visitor you will not care for much of Johnny’s company, and will speedily find your way down the filthy creaking stairs into the reeking outer air, which appears almost fresh by contrast. […] But if you visit Johnny as a customer, you pay your shilling, and curl yourself up on another grisly couch, which almost fills the remainder of the apartment. Johnny hands you an instrument like a broken-down flageolet, and the long supple brown fingers cram into its microscopic bowl the little modicum of magic, and you suck hard through it at the smoky little flame, and—if your stomach be educated and strong — pass duly off into Elysium.

Sometimes a shop was just a shop. Usually run by a Jew, usually selling clothes and allied chandlery. But down the Highway, even these elicited some form of comment. What might have passed un-noted in another city, could not be overlooked here. As ever the reporters differed as to their response. The era’s anti-semitism gave readers the ‘hawk-visaged’ proprietors, with their ‘fleshless hands rubbed joylessly’, their ‘yellow fangs’ and all the predictable badges of the rapacious ‘tribe of Abraham’. Sala, writing for an audience who at least pretended to greater sophistication, preferred to admit that in their determination to bilk poor Jack, both Jew and Christian were equally assiduous.

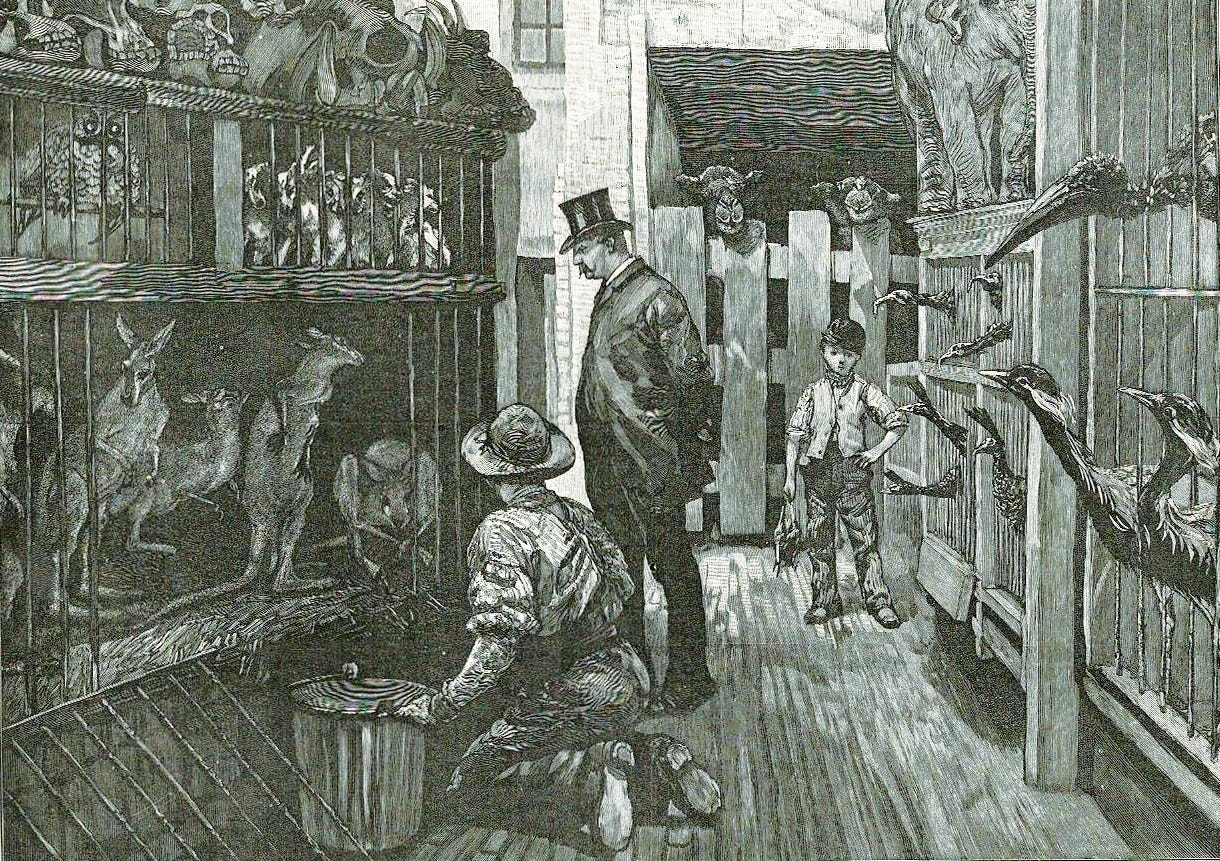

At the same time, for all its social horrors, the Highway also hosted one of London’s most alluring retailers: Jamrach’s Animal Emporium, the largest exotic pet store in the world. The son of a former head of the Hamburg River police, who had first established his family’s commercial connection with the sea and the livestock its sailors brought home, Charles Jamrach moved to London in 1840. He took over the branch of the firm already sited at number 29 and vastly expanded it, buying from ports around the country and supplying public and private zoos, circuses (including P.T. Barnum’s) and conducting a wide international trade. He hit the headlines when in 1857 a Bengal tiger escaped from the Emporium and out on the street, seized an eight-year old boy who, it was claimed, thought the beast was a merely a big cat and wanted thus to stroke it. Jamrach rushed from his shop, dragged open the tiger’s jaw and forced it to drop the child. The ungrateful brat then sued his rescuer, and won £300 damages. The tiger was sold on to circus boss George Wombwell and exhibited to much acclaim. A bronze statue of the rescue now stands near Tobacco Dock, a few paces way from the site of the event.

Victorian morality, noisy, stifling, pervasive, could not tolerate the unfettered self-indulgence of Ratcliffe Highway. Nor was Jack’s systematic pillaging acceptable. Sailor’s homes were developed, which gave him a safe refuge from the whores and liquor shops, buildings were torn down, missions built. And sailors, chastened and finally learning, began simply to go elsewhere. By 1908 it had even lost its name, the road being divided into St George’s Street, High Street Shadwell, and perhaps fittingly, if only to connoisseurs of slang and puns, Cock Street and Broad Street. Today, partially restored as to name if in no way reputation, the entire stretch is The Highway. Victim of Hitler’s own militant evangelism and of slum clearance, bereft of virtually all housing, home to little other than Mr Murdoch’s newspapers behind their wall, it is not, in any sense, a pretty sight.

for GDoS on the root term lubber, see https://greensdictofslang.com/entry/jlv5juy

A search on sailor / sea / boat/ ship for 1780-1850 brings up fifty terms. Jack doubtless took his pick of land-borne words as well. Then there was the vast technical lexis, coined for use onboard.

‘Ark Ruffians Villains, who, in Conjunction with Watermen, &c. rob and murder on the Water; by picking a Quarrel with the Passenger when they see a convenient Opportunity, and then plundering and stripping the unhappy Wretches, throw him or her over-board, &c.’ The New Canting Dictionary, 1725

The first recorded instance of ‘Jack ashore’ I can find comes in The Atheneum, an American compendium of ‘the spirit of the English magazines’ Oct. 1824-Apr. 1825. The magazine is not specified and the phrase appears as a headline.

The use of sailorly jargon seems to be a given of such news stories where Jack, ashore or aboard, invariably converts standard English into what the late Surgeon-Captain Rick Jolly would christen ‘Jackspeak’.

So too, it transpires, surnamed. Aubrey, I find, means ‘fair ruler of the little people’ and yes, rank and decency aside, he is blond, though his crews do not, even when the presgang grew desperate for warm bodies, recruit elves.

‘Marine’ may have meant no more than sailors, but slang’s definitions of fish include a prostitute and her vagina, a respectable woman, both gay men and women, semen and most recently a trans woman who passes satisfactorily for one of her cisters.

To draw again on Patrick O’Brian, the girls seemed to come custom-made. His sailors never pause on the Highway, but there are plentiful mentions of the ‘short, thick girls or youngish women known as Portsmouth brutes’ (The Commodore, 1980) chunky-cut, built low to the ground, far less than gorgeous and very probably poxed. They worked the pubs and cheerfully rowed out to the newly docked ships and stay there until the vessel set sail. Quantity not quality is the leitmotif.